by Enbion Micah Aan

語言:

English /// 中文

Photo Credit: Enbion Micah Aan

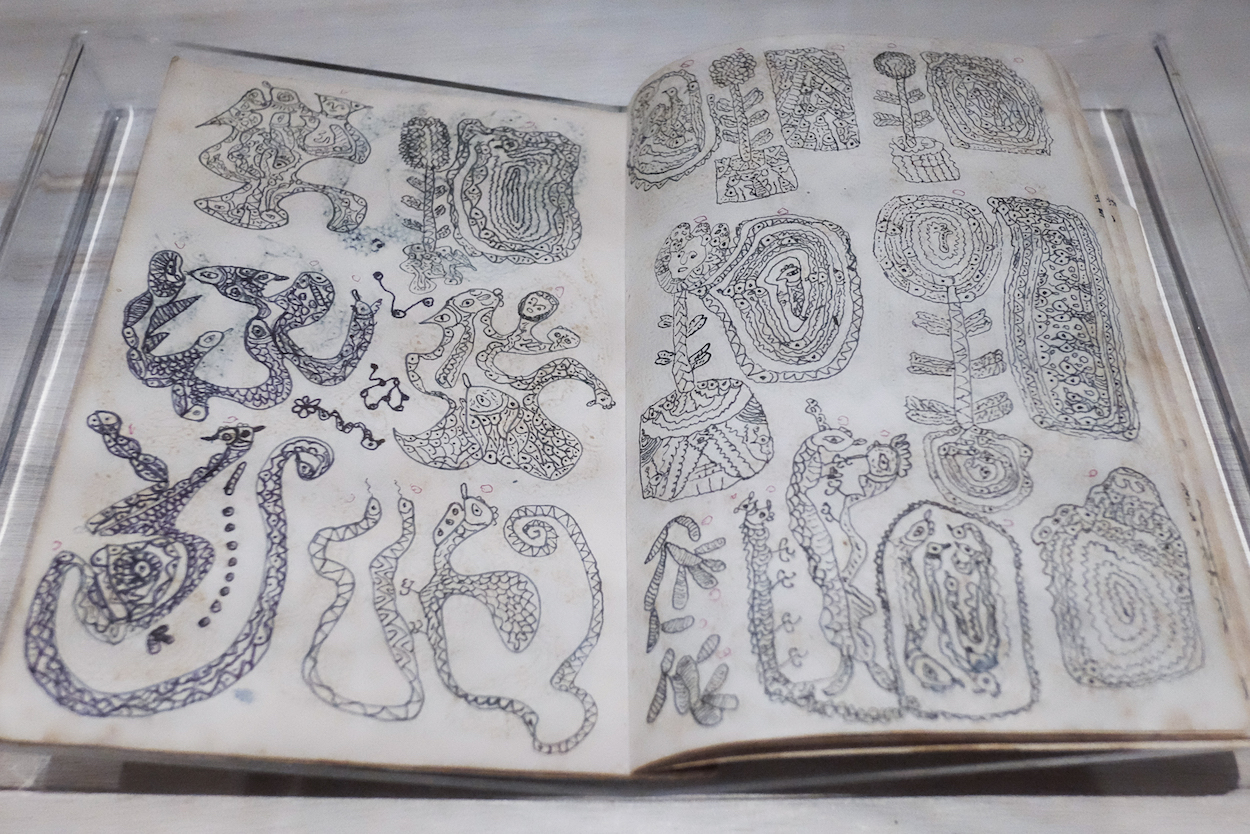

THE TAINAN ART Museum’s solo exhibition on Hung Tung, Re-presention of a Legend: Centennial Celebration of Hung Tung is quite comprehensive, with not only key pieces on display but also information about the media frenzy surrounding the artist. The exhibition also displayed less seen items, such as Hung Tung’s brushes and his sketchbooks. As such, this is an exhibition not only for Hung Tung’s fans and supporters, as well as people who are interested in the media’s role in creating an artist and its relationship to the art world.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Hung Tung, born in 1920, was possibly the first famous artist to emerge in Taiwan since the KMT regime’s takeover of the island. Hailing from Tainan, with a humble and working class background, he decided to start painting at the tender age of 50 in 1970. Thanks to his wife, Liu Lai-yu (劉來豫)’s support, Hung Tung started painting, with her taking on extra work to finance his new vocation. At the time, locals thought Hung Tung went mad, and some claimed he was possessed, possibly because of his experience working as a spiritual medium (乩童). As a painter who was not formally trained, Hung Tung experimented with unconventional paint and paint surface, often using poster paint (廣告顏料) on bagasse boards (甘蔗板). He was right-handed, but he experimented with painting left-handed and also using his penis to paint. To save money, he also used local plants to make paint, most notably, gluing Jequirity Beans (母雞珠) directly onto his paintings. Though illiterate, Hung Tung often imitated writing in his painting, painted calligraphy, and created his own brand of hieroglyphics.

In 1972, a reporter from Echo Magazine (漢生雜誌) wrote about Hung Tung when he showed his work next to a temple exhibition by hanging his paintings on a wall. The next few years, the media feverishly reported on Hung Tung, culminating in an issue in Lion Art (雄獅美術) dedicated to him in 1973 and an exhibition in the US Information Agency (now the 228 Memorial Museum) in Taipei in 1976, where crowds gathered to see Hung Tung’s paintings.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Aided by the media’s obsession with Hung Tung, his fame was meteoric. Despite this, Hung Tung refused to sell his work, claiming that his paintings are all one family and should not be separated. The media continued reporting on Hung Tung for the ensuing years, while he locked himself in his house to work on his paintings, refusing guests and exhibitions. His fame and notoriety caused serious disturbances in his private life, with tourists and curiosity seekers dropping by his house. But because of his refusal to sell his paintings, his living condition never improved and died in poverty shortly after the passing of his wife.

Serious commentary on Hung Tung’s work can be quite a challenge, as his work does not conform neatly to any particular style of painting. While it is easy to see why much art jargon, such as “primitivism”, “nativism”, and “outsider artist” is often used to describe his work, to talk about his art in isolation of Hung Tung’s environment and the historical context would be a mistake. The museum knows this, so it specifically used the French winemaking’s concept of “terroir” to describe how Hung Tung’s art was inspired and nourished by the local culture that surrounded him. Interestingly, the exhibition, perhaps out of concerns that some viewers would think it takes no skills to paint in Hung Tung’s style, had a “Self-learning Trajectory” section to show how Hung Tung developed his skills as a painter.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

It is self-evident that Hung Tung was not a completely unskilled painter as his paintings indicate masterful commands of colors. However, the constant emphasis on Hung Tung’s craft and skills in the medium of painting can be quite misleading—many commentators bestow Hung Tung the status of a “genius” and even more inappropriately, “Picasso of the East”. Unlike Picasso, Hung Tung was not a great painter in terms of techniques, and this is actually quite self-evident as well. As a painter, Hung Tung was no virtuoso. His paintings are highly repetitive. His composition is always the same—always all over. Though his work can be classified as folk art, he was not quite the master painter from the folk tradition like Maria Prymachenko.

It is quite apparent, judging from looking at Hung Tung’s paintings, that he did not understand nor care to have complete comprehension of fundamental pictorial principles, such as perspective, focal point, scale, composition, etc. Hung Tung’s single-minded dedication to the art of painting should not be dismissed, but it is curious that commentators tend to emphasize his prowess in terms of technical skills—an aspect of his art that he clearly never excelled in and is not actually of the paramount importance to his style. To observe Hung Tung’s obvious limited skills and range as a painter does not mean his art should be outright dismissed. Arguably, the appreciation for his art stems exactly from this very limitation. Despite his clear technical limitation, his paintings do transport viewers to a different mental space, most likely childhood, and the accessibility of his work naturally speaks to the power of his paintings.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

The most interesting aspect of Hung Tung’s art may be politics, but this is never really discussed by commentators. Somehow, the fact that Hung Tung came to fame in the middle of White Terror and had his most important solo exhibition in the U.S. Information Agency, a Cold War propaganda institution that sought to suppress the left, is never discussed. Somehow, it is difficult to find historical and political commentaries about an artist who had the front row seat to all of Taiwan’s historical trauma.

Given the unthreatening quality of his paintings, it is easy to see how Hung Tung’s work was allowed to come to prominence during the Martial Law period when a Chiang emperor ruled Taiwan. What is even more interesting is the public’s fascination for his art since the 1970s. Some have argued that embracing Hung Tung is a rebellious reaction to an overwhelming cultural dominance of the West, but this argument misses many elephants in the room—namely, the KMT totalitarianism, the Cold War, the White Terror, and the preceding World War II. What perhaps can explain the public’s embrace of Hung Tung is probably the most obvious feature of his paintings—that they are cute.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Kawaii, the Japanese notion of “cuteness” is not just a style but is very much linked to postwar vulnerability, as noted by Kumiko Sato at the Association for Asian Studies: “The relationship of Japanese culture and cuteness has developed on several different levels in the country’s cultural environment. After defeat in World War II and postwar recovery, Japan’s cultural proclivity toward dependence and indulgence seemed to lead the nation to conclude that its political and economic dependence on the United States was the key to success. This subservient relationship has perhaps nurtured Japan’s “childish” popular culture.

Notably, that Hung Tung’s paintings carry much of this kawaii sensibility and possibly have much in common with Hello Kitty, which also came to prominence in the 1970s, is something most commentators ignore. Given the historical context, it is not difficult to imagine how Hung Tung’s work can psychologically serve to negotiate with the political fact that the population is living in a totalitarian state. The notion of US dependency is also fully illustrated by the fact that Hung Tung’s most important exhibition took place in an American propaganda agency.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

What is also interesting to note, too, is the racial dynamics of Hung Tung. Though there are no statistics around this, it is possible that Hung Tung was not only the most famous artist but also the most famous benshengren artist in the 70’s in the sense that he was racialized, not as a “passing” or “respectable” benshengren. It is also possible that the coverage of Hung Tung started a trend in the media in the ensuing years. The media was controlled primarily by waishengren elite, who recognized the need to have benshengren presence on television and newspaper in order to reflect the ethnicity of the viewership and often resorted to the complete erasure of benshenren Taiwanese identity or claiming benshengren as “Chinese” or “passing” as Chinese, eventually developed the propensity to single out eccentric non-threatening racialized benshenren individuals as human interest stories—a minstrelization trend that ended just fairly recently.

Hung Tung, a painter with a curious brush, an uneducated and illiterate man who went through the Japanese colonization, World War II, 228, and his miraculous rise to prominence right in the middle of White Terror coupled with the media obsession proves to be a fascinating case for anyone who is interested in Taiwanese art and Taiwanese history. Hung Tung may not be the best of painters in terms of his techniques—he does not need to be, but it is hard not to admire his single-minded dedication to his art, the absurdities of his story, the eccentricities of the artist, and the creative energy and joy that is expressed in the paintings.