by Enbion Micah Aan

語言:

English /// 中文

Photo Credit: Cédric Alviani 艾瑋昂 (Von Taipei)

CÈDRIC ALVIANI is a multifaceted individual. Better known in Taipei journalist circles as head of the East Asia Bureau at Reporters Without Borders, Mr. Alviani is also a musician and a photographer.

I met Mr. Alviani for coffee one afternoon in Taipei, and we spoke at length about the state of journalism in Asia and also in the West. When the subject changed to my work as a photographer, we started talking about camera setups, and to my surprise, we use the same very unusual digital black and white camera system. He then mentioned that since I was in town, I could check out his exhibition in the basement of a department store.

Immediately after our meeting, I went over to the department store. I knew little of what to expect—I knew that it is often true that interesting people make interesting work. I also knew that the photographs were made in Paris. These two facts alone added to my anticipation.

Photo credit: Cédric Alviani 艾瑋昂 (Von Taipei)

Any photographic body of work made in Paris is always a little extra special since Paris is arguably the most important city in the history of photography. It was, after all, Louis Daguerre, a Parisian painter who invented photography. Sure, many great minds (for example, Sir John Herschel, Henry Fox Talbot, and Daguerre’s co-inventor Joseph Nièpce) contributed to the invention of photography, but it was the Daguerreotype that was ultimately granted the first patents for the clarity of his photographic process. It was also Daguerre, in 1839, who presented the photographic process to the French Académie des Sciences and changed the trajectory of visual arts forever.

As if having the bragging rights to the invention of photography is not quite enough, Paris also produced some of the greatest early photographic artists. Nadar was possibly the first celebrity photographer in the world. A caricaturist at first, Nadar turned his eyes to portraiture, and photographed famous Parisians of his day—he took the last photograph of Victor Hugo. Nadar is also often credited with the first aerial photography taken from a balloon that was specifically constructed for Nadar’s photographic needs, and the first photo interview. With his experience with balloons, during the Siege of Paris, it was Nadar who helped establish the first airmail service in the world, so Parisians were not cut off from the rest of the world. The Siege of Paris culminated in the establishment of the Paris Commune, and since airmail was the means of communication of the time, with the Prussians surrounding the city and cutting telegraph cable, I would like to imagine that a few of the estimated 2.5 million letters carried by Nadar’s balloons went into the hands of people like Marx and Bakunin. After the Paris Commune, the Impressionists famously were rejected by the Salon, and it was Nadar’s studio where these painters held their first exhibition. It was Nadar whose larger-than-life persona served as inspiration for Jules Vern’s Michale Ardan character in From the Earth to the Moon.

Photo credit: Cédric Alviani 艾瑋昂 (Von Taipei)

Paris, of course, also produced more astute, and perhaps, quieter, photography, in the way of the documentary photography tradition. The most well-known of these photographers is Charles Marville, but it was Eugène Atget who was able to elevate documentary photography above mere visual description of Paris and reached the heights of poetry. Atget’s body of work emphasized the Parisian culture of the craft and pre-industrial era. Atget was apparently very aware of what was going to happen to Paris with industrialization looming and obsessively photographed the city, and seemingly consciously avoided touristy landmarks—in his extensive catalog, there is no one picture of the Eiffel Tower. After Atget, with the technology of photography vastly improved, it was photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau, and Brassai whose street work cemented Paris in our collective imagination.

Historically, Paris, of course, has also been the center of the fashion world (think Louis XIV’s wigs), and many Haute Couture houses of today also hail from Paris. Photography, too, serves fashion in this regard. Some of the great Parisian fashion photographers were also great artists. William Klein, for example, brought the street photography aesthetic to fashion, and Guy Bourdin brought in surrealism and possibly the most splendid color schemes one would hope to see in photography. Klein, not content with merely taking photographs, lampooned the fashion industry in not one but two films (Le couple témoin and Qui êtes-vous, Polly Maggoo?). Bourdin, unlike what one would imagine a commercial photographer would be, was a serious artist whose dedication to his art gave him a reputation of being difficult. (For anyone interested in Guy Bourdin, Faces Places, a documentary by the late Agnès Varda, has a segment about him.) Alas, most fashion photography exists to sell an image and does not even attempt at reaching such heights.

Photo credit: Cédric Alviani 艾瑋昂 (Von Taipei)

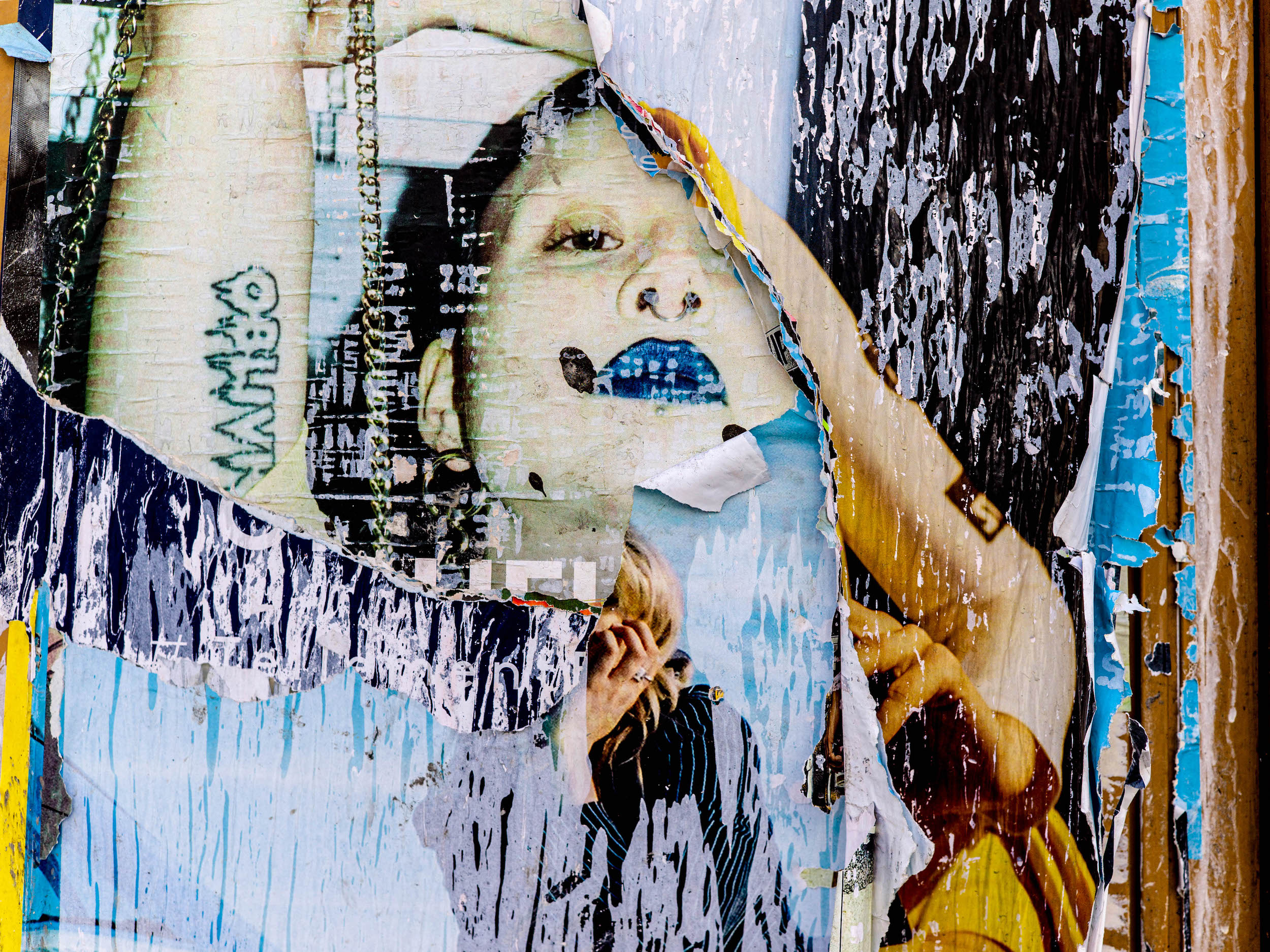

And fashion is where Mr. Alviani’s work shines in its commentary. The photographs were of outdoor fashion posters. Having been through the elements, the fashion statements the posters aimed to make look hollow. The superficiality associated with fashion photography in this context looks absurd. The colorful photographs scream out criticism of our contemporary consumerist world. This subversive commentary of our contemporary “fast fashion” culture is very self-aware, and in fact, is how the exhibition introduced itself: ”Uptown in the ‘City of Lights’, where the scent of urine often masks even the most poignant of chic perfumes, these incongruent scraps of consumerist society have taken on an element of subversion“. The location of the exhibition is perfect for the statement the exhibition wants to make – it takes place in the basement of Shin Kong Mitsukoshi, right below where all the high fashion stores are. This is not to mention that the Paris photographs exhibited in Taipei also speak volumes about globalized capital.

With minimal manipulation of the photographs, Mr. Alviani’s technique is firmly rooted in the straight photography tradition, and the visual style carries a strong anti-establishment punk rock attitude. These are very visually striking pieces that are very much in your face. The interplay of posters, wrinkles, and the graffiti underneath the posters, cries out urban, commercial, and possibly civilizational decay. The photographs also make the perverse nature of capitalist propaganda apparent.

Photo credit: Cédric Alviani 艾瑋昂 (Von Taipei)

And yet, this very in-your-face subversion is being shown in the most commercial of all places, a high-end mall, right below the merchandise that the art is critiquing. The very existence of this exhibition at such a venue highlights a contemporary conundrum – what now that capitalism has learned to embrace, eat, and digest attempts at subversion and criticism to the point that anti-capitalism becomes a vital force for capital? Mr. Alvini’s work in this context certainly suggests this dynamic, much like Slavoj Zizek’s allusions to Starbucks being capitalistic and anti-capitalistic at the same time.

In 1936, several left-wing photographers founded the Photo League in New York City to depict the struggles of the working class. Many great photographers (Berenice Abbot, Ruth Orkin, and Paul Strand, for example) were associated with this organization, and some of the most well-known photographs of New York were produced by individuals in this league. It was also one of the first photo agencies with women in significant leadership roles. One of the luminaries from the Photo League was Aaron Siskind, who was perhaps the first photographer to explore the expressive possibility of wall degradations, specifically, peeled paint and fallen posters. The Photo League was eventually shut down by the government’s anti-communist efforts. In this basement where so many contradictions in our contemporary culture present themselves, I can’t help but wonder that if Siskind was alive today, would his work look much like Mr. Alviani’s?