by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

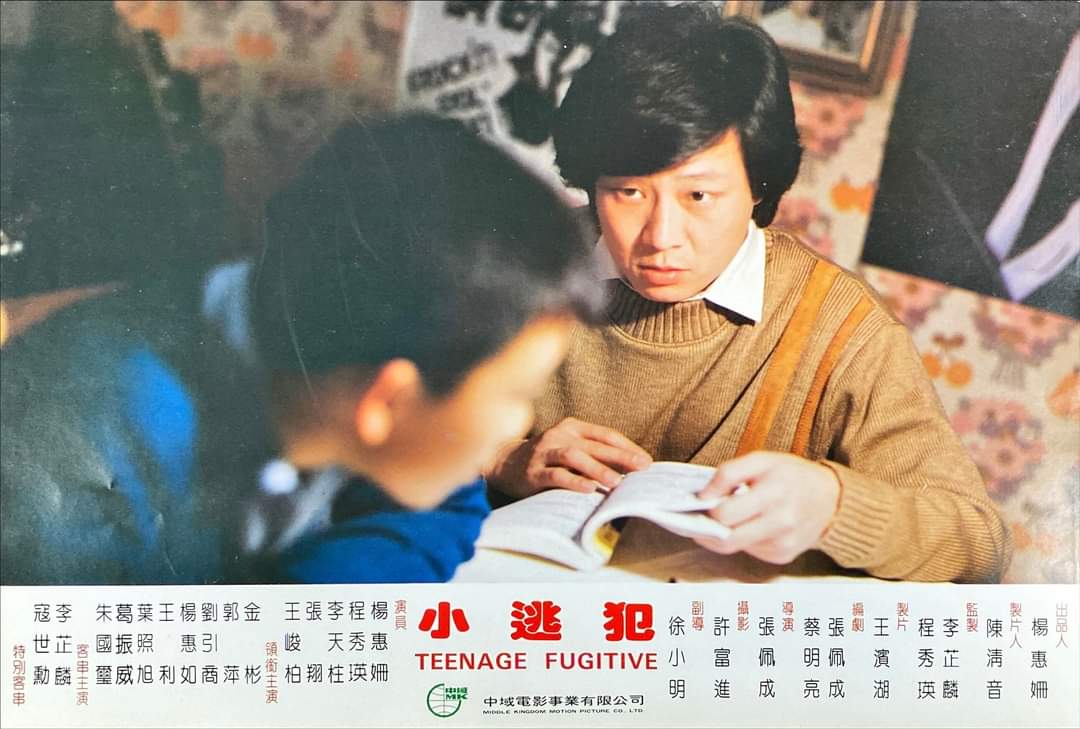

Photo courtesy of the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

This is a No Man is an Island film review written in collaboration with Cinema Escapist as part of coverage of the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival. Keep an eye out for more!

TEENAGE FUGITIVE, directed by Chang Pei-cheng but perhaps most notable for a script co-written by a young Tsai Ming-liang, gives a fascinating look into the historical context from which the Taiwanese New Wave originated.

The 1984 film follows the Zhang family as they are caught up in a series of events after a teenage murderer flees from the police. The youngest son, Xiaohong, unexpectedly befriends the eponymous fugitive of the film’s title, sheltering him secretly in the family’s home.

In the meantime, Teenage Fugitive fleshes out the Zhang family’s dynamics. Xiaohong’s older brother secretly watches his parents’ pornographic films with a friend, while his older sister is preoccupied with Japanese male idols. The Zhang matriarch, in the meantime, tries to balance her duties as a housewife alongside social relations with their neighbors, with whom she frequently plays mahjong.

Photo courtesy of the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

The young fugitive himself secretly watches the family, sometimes finding their interactions humorous. He himself is caught in a moral conflict during this time, feeling that he had no choice in the murder and must continue to flee, but knowing that the police are rapidly closing in on him.

If the Taiwanese New Wave was significantly influenced by Italian neorealism, Teenage Fugitive shows the New Wave’s more humorous side, as demonstrated in earlier films such as In Our Time.

Teenage Fugitive also allows viewers to see another side of Tsai Ming-liang. Among Taiwanese New Wave directors, Tsai perhaps goes the farthest with cinematic experimentalism. However, with Teenage Fugitive, Tsai strikes a lighter tone more similar to that of fellow New Wave director Edward Yang. Likewise, Teenage Fugitive has a more humanistic register than Tsai’s later works, which often highlight feelings of extreme alienation.

At the same time, one can observe some of the concerns that would later come to preoccupy Tsai. For instance, the notion of a group of individuals cohabiting a shared space but experiencing very different subjective realities recurs famously in Vive L’Amour. Nevertheless, as Tsai is not the director of Teenage Fugitive, the movie has a decidedly more straightforward filming style than Tsai’s later work.

Photo courtesy of the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

Teenage Fugitive provides an interesting snapshot of Taiwan during the late martial law period, then, as well as provides a snapshot of the thinking of the early Tsai Ming-liang. If it weren’t for a 2022 restoration, the film might’ve simply been lost to time, or become a historical curiosity. However, this restoration allows Teenage Fugitive to stand out as both a work belonging to, and outside, its time.

In this way, one can see not only the germination of Tsai Ming-liang’s work, but also the context from which he emerged—as well as the transformation in his work over time. After all, even if the relatively dynamic Teenage Fugitive won awards like best screenplay at the 1984 Asia Pacific Film Festival, Tsai’s films have mostly gained acclaim through their meditative shots and sparse dialogue. This makes Teenage Fugitive an intriguing look back at both Taiwanese cinema some four decades past and an early Tsai Ming-liang.