by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

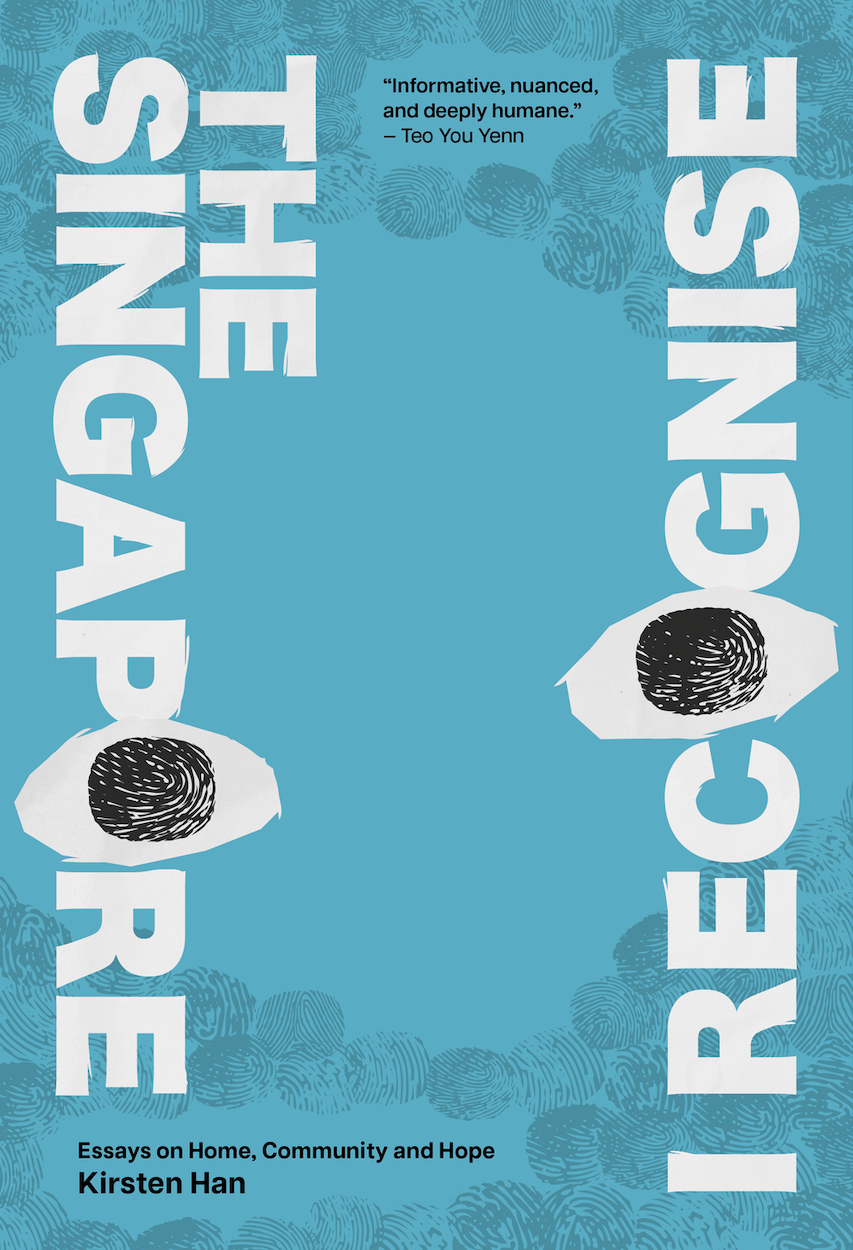

Photo credit: Book Cover

KIRSTEN HAN’S The Singapore That I Recognise provides a glimpse of Singaporean civil society activism in recent years. The book stands out not only as a personal account of Han’s own journey as a journalist and activist, but also with regards to what it shows about Singapore today.

Han’s book takes its title from previous incidents in which government officials derided and denied her account of Singapore, stating that this was not the Singapore that they recognized. However, as Han points out, there are many different Singapores, and some simply turn their eyes away from aspects of Singapore they don’t recognize to avoid reckoning with its uglier realities.

Han details that this was the case for herself, but that experiences studying abroad and experiencing other political contexts came to show her other aspects of Singapore. The Singapore That I Recognise discusses some of the incidents that Han has been involved in through more than a decade of activism and journalism, then, as well as touches upon the experiences of other Singaporean activists. For example, Roy Ngerng’s experiences being sued by the Singaporean prime minister, as well as how the Singaporean government threatened to prevent him from returning to Taiwan during a visit there, are described at length. Likewise, Han discusses some of her work in the Transformative Justice Collective pertaining to advocacy against capital punishment. Han further recounts an episode in which the Singaporean government sought to tar her and other activists as agents working with shadowy external forces to undermine Singapore after a meeting with former Malaysian prime minister Mahathir.

Perhaps what stands out most is Han’s deep investiture and humane concern with Singapore, even as government actors seek to frame Han as disloyal to Singapore or being less than a “loving critic.” But, in this way, Han manages to get at how the Singaporean government has sought to paint activists as hoping for something less than the best for their home.

Indeed, Han’s writing is at its strongest in detailing the invisible red line that residents of Singapore subject themselves to. This is in self-censorship to avoid being targeted by the government, whether in terms of expressing political viewpoints or freely associating with individuals who are politically active in various capacities. Yet to this extent, Han evokes how the Singaporean government has managed to retain power through inculcating society with this mentality of self-censorship combined with discrediting critics with accusations of disloyalty.

The Singapore I Recognise is vivid, incisive writing. The book is not to be missed by any of those who have a stake in Singapore–or stand for democracy and freedom against any government that maintains power at the expense of the citizens.