by Brian Hioe and Florence Yi-Hsun Huang

語言:

English

Photo: Book Cover of Energy Flash

New Bloom’s Brian Hioe and Florence Yi-Hsun Huang interviewed Simon Reynolds about his views on contemporary music and reflections on his seminal work on electronic music, Energy Flash, a quarter decade after its publication. Reynolds was visiting Taipei for a series of talks at C-LAB entitled “A Future Slowly Cancelled.”

Florence Yi-Hsun Huang: Could you first introduce yourself for readers that don’t know you?

Simon Reynolds: I’m mostly a writer. I write all different kinds of things, like books, but also newspaper pieces, reviews, and things, as well as essays. I also blog a lot. So I use all these different kinds of voices. My blog is a much more friendly, informal kind of writing, where I don’t feel like I need to know the answers. Whereas with a different, more ‘official’ kind of writing, I have to do all this research.

In recent years, though, I’ve also become a teacher as well. Well, I’ve been giving lectures and talks for quite a long time, but now I have a job at CalArts, an arts school in California. I work in the music department there. I teach several classes. One is on DIY culture. Another is on experimental pop, which means whatever you want it to mean really. And then I do one called The Elastic Voice, which is about the experimental use of the voice. I can generally pick my favorite music to talk about. So for instance, I do a whole class on Miles Davis and fusion music of the 1970s, some of my favorite music. I do post-punk, techno, jungle music, shoegaze, post-rock. The students are very lively, curious young people, so it’s a good vibe.

That’s me. Writer slash pedagogue!

Cover of Blissed Out

I was born in 1963. As a student, I started writing for college magazines. My friends and I started a fanzine called Monitor. We had just left university, we were living in Oxford, claiming unemployment benefit. But we weren’t layabouts, we were working hard on this magazine, and it got quite successful. Well, it didn’t make money, but a lot of people paid attention to it.

Then I started writing for the music papers. This is the 1980s, when in the UK there were four music magazines–print papers–that came out every single week. So I wrote for one of them, Melody Maker. Then I started writing for other places. I did a book called Blissed Out: The Raptures of Rock, largely about the kind of groups I’d been writing about at Melody Maker – My Bloody Valentine, Sonic Youth, Pixies, Throwing Muses. I met an American, I got married, I was living in America but still writing a lot about British music. This led to a book, Energy Flash, about techno and rave culture. But before that there had been a book about gender and sexuality, a feminist book about rock that my wife Joy Press and I wrote together called The Sex Revolts. Then I did the post-punk book, Rip It Up and Start Again, in 2005. Then Retromania, in 2011, and the most recent book is called Shock and Awe, which is about glam rock. That’s sort of my career to date.

I liked dance music from the start of being into music, really, because post-punk had a lot of funk, disco, and reggae influences. But a big shift in my life was that I had mostly been writing about alternative rock and early rap, then I had this experience around 1991 of getting involved in the rave scene. Although I was 28 then, I felt like a teenager. So I had this adolescence that I really hadn’t had as an actual teenager, when I was introspective and a big reader of books and already writing a lot. But now here I was, in my late twenties, going out and dancing all night, staying up. And beyond that, beyond the fun, it was very intellectually and politically interesting. You just saw this culture emerge and it split up into all these different directions. Some elements were very European, other elements were very Caribbean influenced. Then jungle music emerged and it was very reggae-influenced and influenced by sound system culture. Very working class too.

Cover of Rip It Up and Start Again

The other thing that was big in the UK, particularly in London, was pirate radio. Illegal broadcasting. Almost no political broadcasting, though—it was all music. I feel like all of that youth energy in the UK that could have gone into radical politics goes instead into aesthetics. This kind of militancy that people felt about music–jungle, hard techno, or other genres of music. There’s a kind of mobilization of people, but for the cause of music. People would use words like “cause” to talk about rave or jungle –almost military language.

Pirate radio station in 1992 defending itself against police and local government allegations

Brian Hioe: Do you think it had to do with the Thatcher era?

SR: That’s something people have talked about–raves as expressive of a desire for unity and collective experience, people gathering together. There was that element. But there was also kind of a capitalistic element, since people were hustling to make money to eat. Selling t-shirts, records, and there was a lot of crime involved. It was a weird mix of idealism and hard-headed graft.

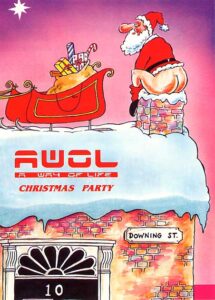

But for sure, rave had that element—people who felt they were oppressed, who were finding their spaces in these raves and clubs. For pirate radio, there was this kind of insurrectionary energy to it, but there was also this total distrust of all politics. I found various rave flyers that had jokey political themes. There’s one where Santa Claus is sitting on 10 Downing Street, where the prime minister lives. He’s landed his sledge on the roof and is taking a shit down the chimney. It was kind of like “Fuck off, all politicians.”

AWOL flyer mocking the governmen

And I don’t think it’s just because it was a conservative government in power at that time. They would have had the same attitude to a Labour government. They didn’t think any politicians cared about them at all. But it depends. That’s the very working class scene. There were other people, like the free party scene. More like hippies, very political in a way, but also kind of “fuck the system”.

BH: I’m curious how you would reflect on what has changed in the 25 years since Energy Flash came out.

SR: A lot has changed really. It’s almost hard to know where to begin. I’ve been living in America for a while, so the British scene I have less firsthand experience. But what I gather is one of the big changes in Britain is that it remains a multicultural scene but where once most of the Black influence came from Jamaica, in recent decades the majority of Black people in the UK actually come from Africa. And that’s changed the whole feel of music–there’s a lot of Afrobeats and all these different sounds. African-British people have a different relation with colonial history, they experienced colonization but unlike with Caribbean people, there’s not the narrative of slavery and being transported over.

Political and militant grime performance (by the MC Durrty Goodz)

It’s hard to generalize. But It’s something you notice with grime – that the MCs and producers, they have their artist name but their actual real name, it’s an African surname. With jungle, it was more often the case that people came from Jamaican backgrounds, Barbados, or other places in the Caribbean.

There’s been this interest in South African house music, amapiano, which is different since it’s a different part of Africa – Afrobeats comes from West Africa, in particular Nigeria. But amapiano is part of this African moment in dance music. And some years ago we start to hear about the Sound of Lisbon, which is another form of postcolonial hybridity. Portugal had a small empire, some of those African people moved to Portugal just like how Jamaicans and later people from Nigeria and Ghana moved to the UK. And just like with jungle and UK garage, a hybrid sound of African rhythms meets techno and house emerged in Lisbon. Very strong, stridently percussive beats, with a completely different feel to the music that has the reggae influence. Much less about the bass.

BH: It seems as though that has to do with shifts in globalization, or transnational movements.

SR: I think so. Immigration, refugees, but also tourism. People travel more. But also there’s this discussion about air travel can be bad for the environment, so deejays doing all this travelling, or ravers flying to Berlin or Barcelona for the weekend, it’s a bad idea. There’s much more awareness about gender and minority identity that has become much more explicit in the club scene. Before it was more of an undertone, as in everyone knew that house music came from gay culture, but there’s much more of a militant inflection now. People feeling embattled and that they need safe spaces.

BH: I also feel like there’s this framing of electronic music as this international culture of solidarity.

SR: Generally, it seems more politicized, with work that explicitly carries political themes. Before, I think there was this more vague feeling about unity, that everyone is welcome here, and these sort of utopian politics along those lines.

BH: Could you talk a bit about nostalgia? The longing after these different aesthetics in disco or jungle, or these different aesthetics that come up in this way.

SR: Through people like myself, and others that have come along later, there have been all these histories written. There’s a big interest in lost narratives being discovered – scenes and sounds and moments that never got written into history, until now.

I noticed this starting after 2000 or so. Before that there was a history, but we didn’t just think about it. Techno felt like future music, and the emphasis was not about tracing its roots but emphasizing that it seemed to come out of nowhere. As a writer, it didn’t seem to remind of anything. So instead of breaking it down to its sources or constituent parts, writers like me or Kodwo Eshun, we’d use a lot of new words. We’d come up with neologisms. We combined two words into one, what they call a pormanteau.

BH: It reminds me of the Walter Benjamin quote about the poetry of the future.

SR: I love history and in fact, I studied history at university. And I have become a kind of historian with the books. But I think there was a general future orientation in the writing about electronic music in the ‘90s. Kodwo Eshun really took this to the extreme, he felt there was a kind of ethical imperative to emphasize what he called the discontinuum: breaks with the past. Almost as if these sounds were literally coming from the future, like the Terminator. Which is definitely a more exciting way to think about it.

Jungle was a huge thing for me. And while it would have echoes of reggae in the bass and it would sample voices from reggae or hip hop or soul music, the overwhelming orientation of the culture was pushing forward. It would use the past as material to rework, but it wasn’t particularly honoring the past. I think it was the same thing for hip hop as well – the past was a set of resources to be repurposed and reactivated in the present. When you sampled something, it wasn’t a tribute to ancestors. If anything, it was more like grave-robbing!

Back then, there was no way to find out the kind of information we now take for granted, the back story of funk and disco and reggae. Think about it—there was no YouTube, the Internet didn’t really exist for most people. If you wanted to find out about the past, you would have to go to a library. A university or something – and call up old magazines. There weren’t many books even, compared to nowadays. But now all these clips from old TV footage or documentaries are on YouTube. You can find out about jungle, pirate radio, techno, you name it. There are endless blogs or online magazine articles on these obscure areas of dance music history. As a result, there’s a kind of museum element to this culture that didn’t exist before.

BH: Interesting. But I also wonder about how there’s increasingly more citations in music and callbacks to previous things. These callbacks to previous things. It seems to be very postmodern but also post-internet.

SR: That’s going on a lot. Even the Beyonce album, there’s one song, “Summer Renaissance”, where she both quotes and samples from “I Feel Love” by Donna Summer. There is this sense of honoring history, whereas I think when people sampled things in early techno or house, this wasn’t honoring ancestors or a citation, this was just a cool riff–something they could use. And they sampled all kinds of things, from movie soundtracks, pop records in the charts that month, all sort of trashy things. Just kind of repurposed it.

BH: Are there contemporary developments in music you find exciting?

SR: I’ve sort of reached this point where I love one record a year and then I like quite a few others, but almost none of them have that overwhelming effect on me. I do really like the Nia Archives stuff. Initially I thought it was a bit lame of me to like it so much, given that it is based on jungle, which is my favorite music. But the way that Nia Archives weaves her own voice and songs through those kind of beats – it’s really effective, absolutely gorgeous. And I like the Pink Pantheress stuff, which does a similar kind of thing.

But overall, in a funny sort of way, I’ve become drawn back to…not exactly indie music, but music that has guitars in it and the lyrics are really saying something. So this group Dry Cleaning is my favorite group in the past few years. Their first record New Long Leg is more post-punk influenced and their second record Stumpwork is more expansive soundwise. Musically, it’s the guitar-bass-drums format. What makes it stand out is this woman Florence Shaw who speaks the lyrics rather than sings them. She’ll break into a certain melodious cadence every so often, but it’s essentially spoken word over rock music. The use of language is brilliant, but in terms of affect, it’s quite depressing. It seems to speak how things are in the UK – which is bleak and grim, especially for young people. Her affect is numb, her voice is often very tired sounding. The second record has moments that are slightly more optimistic in mood. But on both albums, the lyrics are very funny and brutally honest and just weird. She uses fragments of things she’s overheard when traveling on public transport, strange bits of language she’s found in shop signs or Internet–advertising speak–but she’ll weave in her own feelings and thoughts. And the end result is very moving, I find.

I don’t know what was the last dance music thing I really loved. I was really into trap for several years. It is dance music, not in the Energy Flash way. But what really grabbed me about it was the amazing things people do with Auto-Tune. Funnily enough, the opposite of Dry Cleaning, which is so lyrically rich and meaningful. In this Auto-Tune trap, the words are kind of irrelevant. It’s all about this abstract mutation of the voice. With someone like Future or Playboi Carti or Migos or Young Thug, it’s often just weird sounds the rapper is making. And the rapping is somewhere between singing and rapping. With Auto-Tune, the technology finds the melody in human speech – so rapping starts to blur into melodic singing, and rappers learn to push that effect. They start moving into this zone which is neither pure rapping or pure singing but something in between.

There are lyrics and they tend to be the usual sort of trap subject matter—boasting about cars and girls and drugs. But strangely they don’t come across as macho. Because the Auto-Tune has this effect of making them sound vulnerable and sensitive, androgynous and angelic. They might be boasting about their expensive watch or making these horrible threats, but it doesn’t come across as tough, it comes across as sad. Often the feeling is a kind of melancholy hedonism—they’re at the party, having this wild time, but it’s not satisfying. Drake kind of invented that—the hollowness of fame and wealth.

I like some of the amapiano music. It obviously means something in South Africa. But the vibe I get from looking at the videos is similar to trap or upmarket forms of club music. Well-dressed people looking very flash and waving bottles of champagne. The structure of the rhythms and the way the bass moves is very interesting, but as a culture, I don’t know if it signifies much more beyond good times music.

BH: Would you say the way that people find music has changed? With, say, the decline of people going to record stores and now finding music online on the Internet.

SR: The way I use the Internet is actually a bit like going to a record store. I click around and go, “what the hell is that?! I never even knew this group existed.” I do stumble on things though chance. There are various ways of making that happen like going on Discogs and purposefully looking for things and you’ll accidentally find something else in the process. There is a sort of randomness wandering around on the Internet, especially if you go to things like blogs. Random people will remember something and throw it out there on Twitter and if you’ve got a spare minute, you may click on it, and encounter something you’ve never heard of before. I think there’s some randomness available. But with algorythms, there’s something sinister about the idea that someone knows that you want. It happens when you’re watching a TV stream as well, based on what you’ve checked out before, things will be ‘surfaced’ that they think you’d like.

Once upon a time I used to follow critics–I religiously followed certain writers and bought most things they recommended. It usually worked, most of things they recommended were great. I probably still carried on doing even when I was a writer myself and could hear almost everything myself. But at this point, it doesn’t seem to happen anymore for me – following the guidance of experts.

I was asking my students how they found out about music. They don’t read magazines, they just pick up on things through social media. When they discover something they like, they might go deep into research on that and that’s when they’ll do some reading. They get really deep into the back story. That adds to the enjoyment in a lot of ways. It’s a bit like this term “lore.” Like folklore or a story or a fairy tale. A myth or legend around a band or label.

The term ‘main character’ is also interesting, how people see themselves as characters in a game. I missed the whole era of games. I was just a little too old already when they really took off at the end of the 1980s. So a lot of these words seem surprising to me. Like “nonplayer character” as an insult!

FH: What do you make of contemporary shifts in writing on music? There seems to be less of it these days.

SR: I think there is still quite a lot. Books still seem to be in demand, though someone said it was all middle-aged people buying them, so perhaps that is just a temporary boom. Young people get in contact with me that have read my work and are excited about it and I can tell they’re reading other books. But it seems to be a bit of a minority interest among young people. It’s a big thing to ask someone to read a book these days, there’s so much stimulation, and so many things competing for your attention.

I find it hard to read books, I’m probably reading more than ever, but a lot of it is online, it’s news, or endless analysis of Donald Trump and what’s going on in America, and I am reading quite a bit on music, arts, and cultures. But though I read books, it’s not as often as I used to. I have about 300 books I haven’t started and I have a long list of books I want to get to. I think there’s still probably an appetite for context explaining what something means. With just sounds, it’s not enough, you still need to know the story–what it means, if it’s old music what effect it had when it came out originally, and with new music, it’s much more exciting if it’s not just a band on their own, but if it’s in a scene or captures a mood–like with a band like Dry Cleaning. They are actually part of around 20 bands in the UK that do the talk-sing thing.

But if you can connect what a band is doing to the state of the country, the state of the world in 2023, it makes it more interesting to have this sort of macro-text. I’d like to think people still want that – need it, in fact. There’s still something to be said for the kind of piece where you connect a whole bunch of things together. Or even if the piece is about just one record, going deep into the world of that record. As a supplement to the record, that kind of criticism is very valuable. I personally also enjoy reading negative pieces, even about things I like–finding that something I love didn’t do anything for someone else, or that they actively disliked it. People are different – it’s interesting how and why we react differently to art. I grew up with that kind of negatve writing, so I’m programmed to enjoy that.

When musicians get worked up about a bad review, it shows they crave attention, the validation, even simply being taken seriously. A piece of criticism can help them understand what they are doing better than if they were left to their own devices. Some musicians–not all–get something out of this kind of writing.

FH: What do you think has changed since you wrote Retromania?

SR: I’m speaking about that tomorrow. The funny thing is that everything the book describes is still going on and new forms of retro phenomena have happened since 2011, when the book was first published. In some respects it feels like there’s been an increase of retro. There were a lot of articles in newspapers and magazines last year and this year about revivalism or other retro syndromes. And often the writers would quote from my book. Retro seemed to be resurging as a topic.

At the same time, I felt like there has been quite a lot of new futuristic things happening. Music, especially a few years ago, especially with all the trap using weird Auto-tuned vocals, and then some of the deconstructed club stuff, like techno or conceptual stuff, often also doing things with the voice but not in the context of hip hop. Doing it more in the form of the Berlin experimental scene. People like Holly Herndon.

And then all this technology. Deepfakes and AI. Those are futuristic, but not in a good way—scary futuristic. I feel like retro culture is as big as it ever was, really. And then are lots of new retro things like hologram tours. It seems very sinister to me. You can take a voice of a dead star and have them sing onstage in realistic-seeming performances. I imagine we are at the point where you can digitally simulate or replicate the voice of a dead singer and have them sing new songs. There has been talk about having dead stars act in movies, like James Dean. James Dean only acted in three movies in his life. But there’s enough information there that they can digitally simulate his mannerisms, his gestures, his facial expressions, as well as his voice—and they can make a simulacrum of James Dean play new roles in new movies. That’s very disturbing.

So that’s retro, but sort of retro and futuristic at the same time. It’s like science fiction with an element of retro. So I think the book is still relevant about this necrophile retro-culture.

That said, there are various criticisms of the book that could be mounted. The book is very much about music and the idea that music should be coming up with new sounds. Both me and Mark Fisher, our retro critique is very much bound up with sonic innovation. That’s just one kind of innovation. There is another kind which is about lyrics – new, original ways of writing, new kinds of emotional content. You could even talk about innovations in personality – the kind of subjectivity or persona in pop music. Or the mode of singing and vocal delivery, as with Dry Cleaning’s Florence Shaw. Their music is almost traditional – “good old fashioned post-punk”, on the first album New Long Leg at least. Almost like if post-punk had become a style like the blues – a finished, settled style rather than an experimental process as it was originally. They abide by the rules of playing post-punk music. But what’s new in Dry Cleaning is the mode of singing–or not-singing. The vocal delivery. And the lyrical content.

Similarly, a lot of the interesting music today is new less in terms of musical form but more because of the emotion content – it is expressive of queer or trans subjectivity. Or it is about feelings and affects that are unique to our time. A certain kind of sadness, anxiety, and overwhelmed nervous strain in the face of information overload. All bound up with digital technology and social media. That’s the element in the music that makes it modern, makes it contemporary.

So my thinking about “retro” has opened up a bit. It’s good to do a book and then change your mind, rethink it, have new ideas, or end up disagreeing with yourself. If you write a book, the book should not be the end of the process, the last word on the subject. The book continues to get written even after it is published, through the process of other people responding to it and saying ‘you’ve got this wrong’ or ‘you should have talked about that’. The book continues to get written in your head too, because your thoughts keep on developing. When I did Retromania, I did a huge number of interviews with magazines and on the radio. I also did many public appearances. People would say things to me in the audience, sometimes angry things, or violent disagreements. So I’d have to instantly think of a response. It came out in a whole bunch of translations in different countries, each year it seemed like a translation would come out, so I would do more interviews, or there might be a book tour. As a result of this kind of prolonged exchange of views, I actually had sharper ideas about the subject later on, several years after the book first came out in the UK. So the book is not the end of the story. There’s more that develops after it enters the world–hopefully. If you do a book that people talk about and disagree with, that’s a great result.

FH: I’m curious about how you see the Y2K phenomenon. The panic about the year 2000 and attendant social phenomenon. For example, the genre of hyperpop. Many of the sounds and aesthetics, and how the artists dress themselves, according to the year 2000.

SR: I suppose in some ways, it seems inevitable. It’s been twenty years since then. That’s the traditional gap for when something becomes a site of nostalgia. So right about now would be when the Y2K period starts to get looked back to. Also, 1999, 2000, and 2001 were quite an optimistic period in pop culture—the economy was doing well, and much of the pop music of the period was very happy. It makes sense that people would be drawn to it. There was Missy Elliott, Daft Punk, and Britney Spears. There’s always bad things that happen in the world, but it was a relatively stable, optimistic time. Then after that, you have 9/11 and the Iraq War, the economy went bad–from a Euro-American perspective, at least.

FH: We’re kind of a more DIY publication, so we were curious what you’d have to say about music journalism, as well as the relation between politics and music.

SR: I’ve always been uncertain about the role of music and politics. I’ve never been able to make up my mind what power songs have. I think music can create communities, people who are isolated or oppressed or just lost in some way. Alienated. They can find a strength in a community based around music that is expressive of those feelings. That’s clearly something that happens again and again, particularly with minority groups. The music itself may not have any explicit politics, but the politics is the culture that surrounds the music. A lot of gay music in the past, as with disco and house, does not really have an explicit political message beyond a general ethos of love, unity, tolerance, and acceptance. The song lyrics have largely been about dancing, sex, romance, staying up all night, escapism. But the politics resides in the space created around the music.

Same with a lot of black music. Black music, like R&B or dancehall reggae, is often about having a good time, dressing up in our best clothes, we’re here to party. But having the space to do that provides a vital social function that is, if not political, at least proto-political. It has a political or social value. It doesn’t need to be directly critiquing government policies or racism, because all that is understood by the community anyway. The point of the music is simply to build something that says ‘this is our space, we are free to be ourselves here, and have a good time in spite of all the bad shit’. There’s a politics to that.

Whether songs change people’s minds, I can’t be really sure. In some ways, the best thing music can do in terms of politics is make people feel good. They can feel they’re not alone or they have people on their side. We shouldn’t necessarily expect pop or any other kind of music to be a form of enlightenment.

When I grew up listening to post-punk music, it was things like Gang of Four and Scritti Politti. I did encounter ideas through them that had a profoundly illuminating and stimulating effect. Yet I wonder if, given the kind of person I was, I might have found those ideas anyway. Perhaps a little later, but soon enough. Because I read books, I was political-minded, I was an aspiring intellectual, I was interested in theory and philosophy. I was already ripe to respond to these ideas in Gang of Four and Scritti Politti.

So it’s hard to say what the actual political power of music is. But one thing I would say is that with politics and music, if you add politics to music, it often makes the music better. It gives it a sense of urgency and motivation. People who believe that music has the power to change things, they often make really strong music as a result of that belief.

I would almost say that politics has done more for music than music has done for politics! Then again, historically, there have been moments where political songwriters have been very important. Bob Marley, Victor Jara. If these kind of singers weren’t dangerous…Jara would not have been killed by the Chilean regime, if his songs hadn’t been seen as threatening by that regime. So it must have some power. If people at the marches and demonstrations are singing your songs or the authorities try to ban your records, that implies there’s some kind of power.

Like with postpunk, deconstructed club has a discourse around it that is very critical. That must have some kind of effect on consciousness. People think about this music. The people making it and the people listening to it.

FH: I’m also curious because rock music has this history of being rebellious or making people have this sense of awareness of the system. It has been this sort of tradition. But what about the tradition of electronic music being political–or is it anti-political?

SR: It’s interesting you use the word anti-politics… Sometimes music is a refusal of the political. A lot of rave culture was like, “Fuck the system, we’re going to make our own world.” That was part of the meaning of the word underground. The government isn’t doing anything for us, the police are against us, it’s hard to get good jobs, but we’re going to create this subculture that is our own little utopia or heaven on earth. Our place, where we belong. So it’s a refusal of politics as conventionally understood, the realm of elections and political parties and pressure groups.

There have been other moments in music that have been like that. Reggae music in the 1970s. Some indie music in the early days, that was a refusal of wanting to have a job or living a conventional life. In a way, organized politics was part of what was being rejected.

That said, I think if you want to change the world, there’s no shortcut to actually getting involved in conventional politics or activism. Whether its electoral politics, or organizing around a campaign or issue. And music seems to play a role in that. People are always playing music at rallies or benefits, people have songs they sing. It creates a sense of unity and purpose. Although the real work is the organizing.

FH: I think politics is not just going to vote or attending some parties or going to the street, I see it as how we perceive or engage with this world. Paying attention to specific social issues, being part of a discussion, and some public engagement. When people rave, sometimes we talk about politics and have a sense of community, but how can we go farther to have this–to go beyond this capitalist society?

SR: You want to take these magical moments and articulate them into a longer scheme of making things better. I haven’t got any good answers. I’d go and have these magical experiences like you’re describing in clubs and then I’d wonder, is this leading anywhere. Are we all just burning our brains out? I don’t think anyone has really come up to an answer to that. It feels like something important is happening in the club or at the rave, but how do you translate that into everyday life and into long-term politics?

Maybe you don’t need to, maybe it has a significance in itself, and has a valuable, therapeutic function for a lot of people. There are stories of people who have had their personalities changed through raving and became much better people because of it.

FH: I’m curious about what you think of when you think about Asia.

SR: In Retromania, I make this very vague suggestion that maybe the next thing in music will come from Asia or India—places where the population is relatively young, there’s a lot of economic energy, but there’s still this traditional culture. And that culture is being torn apart by all these new forces and pressures—the Internet, the way the whole world is connecting up. The scenario I imagined is similar to what happened historically when rock and roll emerged, or earlier, when jazz emerged. You had the collision of traditional, local music forms and recording technology and mass media. It’s exactly what happened, but in the 1950s it happened in the southern states of the USA. A local music form managed to spread like wildfire because of television and records. It took the rest of America by storm, and then the whole world.

So I was wondering if something like that could happen in the East. Although the civilizations here are among the oldest on the planet, something feels younger about this part of the world. I don’t find K-pop interesting myself, but the energy of it. A lot of the energy is coming from business, this sort of hyper-capitalism. People talk about the Asian Tigers. For Europe and America, maybe their time has come in terms of being the source of where things come from.

When people from the West come here, what catches their eye is often the most traditional thing, so they’re not necessarily attuned to the new things that are happening. Since what they immediately notice is what is most unfamiliar to them, and those are usually the residual elements of the culture, rather than the emergent ones. So in some ways, what catches my eye here will then be the most conventional or old-fashioned things. But I’m noticing what is most different from what I normally encounter back in America. Ironically, when you visit as a tourist, you’re mostly visiting a country’s past–the churches and temples, the countryside, the cathedral, the ruined building or palace.

What I like to do when I go somewhere I’ve never been… See, I could go to museums, but I’ll probably forget all the beautiful and precious artifacts I look at. What I’ll actually remember is the feel of a place and the vibe of a people. So my favorite thing to do is go to a street market or a food market, which is where the soul of a country resides in many ways. But young people who live here, probably what they are most interested in are the things that are breaking with tradition or the everyday.