by Enbion Micah Aan

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Hayden Schiff/WikiCommons/CC

IN 2016, Trump shocked liberal Democrats. They should not have been shocked.

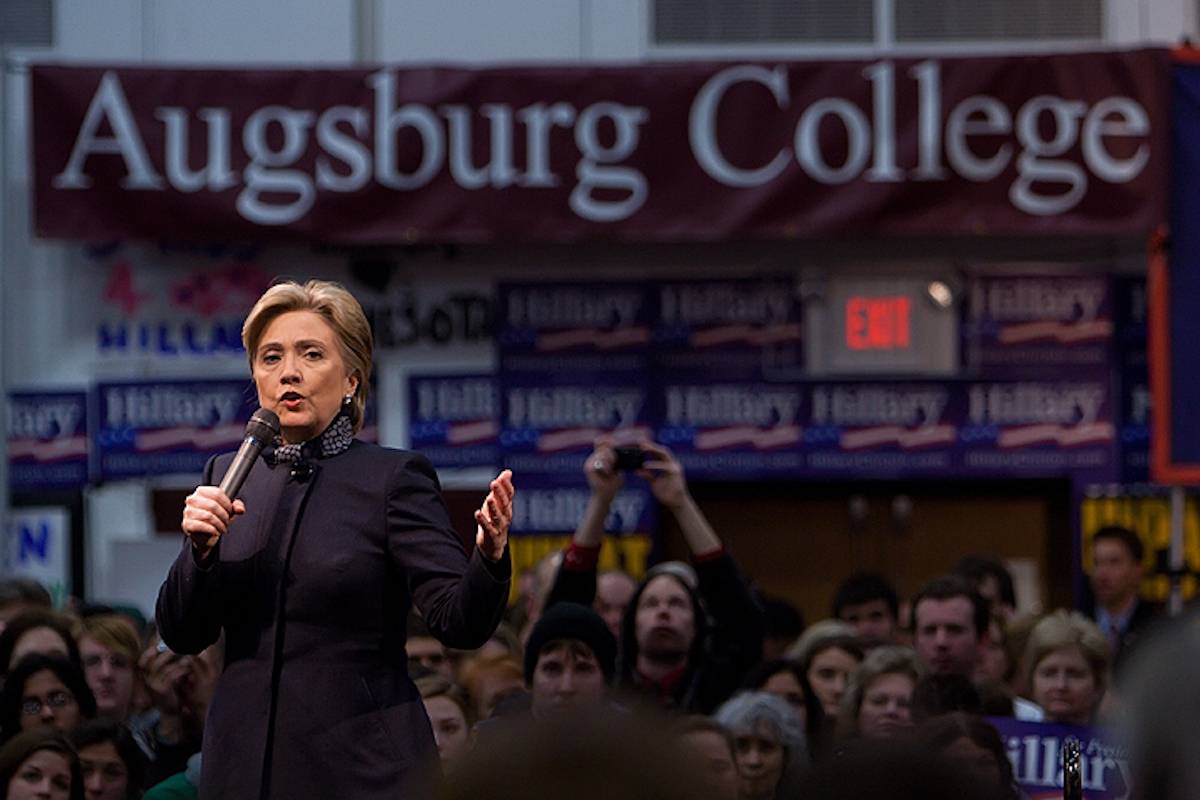

It takes a certain level of ignorance and magic thinking to believe in their candidate at the time. Hilary Clinton, after all, is the spouse of a president whose trade policies were largely responsible for the closing of factories and deindustrialization of the nation. After the factories closed, these same towns saw their mom and pop shops close when Wal-mart moved in. Hilary Clinton was a board member of Wal-mart. Imagine, now, if you lived in one of these unfortunate de-industrialized zones, and were told that you are sexist, racist, and, in fact, deplorable, if you do not want to side with the DNC when their very candidate has caused great pain in your town, wouldn’t “Crooked Hilary” sound just about right?

Hillary Clinton. Photo credit: Calebrw

Liberal Democrats today are neither Liberal nor Democratic. Liberal Democrats today no longer tolerate debates, preferring to shut out all dissenting opinions and compete with others in their moral purity. Meanwhile, internally, the DNC does everything it can to shut out its left-wing insurgence and close opportunities to organize its party around working class issues. “The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains.” were Marx and Engel’s immortal words, and contemporary Democrats want us to have handcrafted chains that are made in a prison, managed by a diverse staff, and all involved in the making of the chains are polite enough to use PGP’s.

How FDR’s “Party of the People” morphed into a Party of Elites is the central theme in Thomas Frank’s new book, The People, No. It is a moving account of 1890’s Populists and their enduring legacy, and how the meaning of the term, “Populism” coined by the People’s Party in 1890, changed from a word that is associated with class struggle in America, to signify the ignorant, anti-intellectual masses everywhere globally. Nowadays, “Populist” simply means whatever liberal elites do not like, but the origin of the term suggests a great optimism in America’s own class struggle.

In 1890, the American People’s Party waged its French Revolution, without the guillotines. Although the People’s Party’s movement ended in a resounding electoral defeat, these ideas endured through the 30s, and later culminated in FDR’s Presidency, which built the modern progressive policies we know today. This Populist sensibility that emphasizes class struggle and an economic democracy showed up numerous times in American history, and Franks’ moving account of this class struggle is an endearing effort to explain to readers that class-based movements were once very significant forces in American politics that ultimately shaped the nation in ways we do not realize.

Frank has the rare ability to speak about serious political issues without taking himself too seriously and to write in a way that is as moving and penetrating as it is entertaining. However, If one needs to nitpick, it would have to be the extraneous concluding section after the book already presented itself with a perfect ending with a poem by Carl Sandburg. The book would have ended with a positive Populist sentiment and without predicting fundamental changes to come. This concluding section feels quite obligatory and Frank, perhaps wanting to cheer up to activists and organizers who are currently under COVID-19 lockdown, verges on making predictions here.

Morris Berman, one of the most prescient historians on the subject of American decline, said of Chomsky’s work as “removing the wool” from people’s eyes. The problem with this approach, for Berman, is a “false consciousness” argument, or the claim that the ideas were injected by the evil elites, and once the “wool” is removed from people’s eyes, people will see the truth and a leftist revolution is sure to come.

But if one is to examine more closely, as Berman has, it is not the case that the American electorate is simply misinformed and unaware of the manipulation of the elites. What if the electorate genuinely prefers demagogues such as Trump and the slick political maneuvering of Obama and the DNC? The question is entirely different if the People no longer hold democratic ideals as sacred and founding principles of the nation. After all, in every election, voters are free to choose, and the electorate has always sided with anti-Populists whether in style or content, as Frank himself observed, when the deceit by both parties is actually quite obvious.

Despite this, voters have consistently, for decades, voted for politicians who serve elites’ interests. The Republicans did not hold guns to their primary voters to vote for Trump, nor did the DNC force their voters to not side with Bernie Sanders. John Steinbeck who also witnessed the same decline of the leftist forces in The People, No, observed: “Socialism never took root in America because the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.”

Cover of The People, No

As excellent as the book is in sketching out the dialectical relationship between “populism and anti-populism”, how class struggle is necessary for change and reform, how important bold economic reforms are needed, how our fundamental attitudes toward politics need to be transformed, its concluding section seems extraneous. One notes that it feels like an obligatory and feel-good optimism that is aiming to be aspirational more so than it is rooted in actual political circumstance.

Thomas Frank has always been an astute political observer, but it indeed takes a special talent, in talking about Populism, to capture the spirit of important leftist social movements that emphasized class struggle. The People, No ultimately captures the positivity and the spirit of the past revolutionary attempts, in the democratic belief in people, in the education of the masses, and in a government that should be for the People, by the People. Although I may not share the positive outlook stated at the end of the book, Frank’s reason for optimism is well argued in the way that it urges us to take a leap of faith toward leftist, working class organizing and away from existing power structure and cynicism, and it is a special experience reading a book with penetrating political insight that can potentially counter the prevailing lefty pessimism in the Trump era and afterward.