by Enbion Micah Aan

語言:

English /// 中文

Photo Credit: Enbion Micah Aan

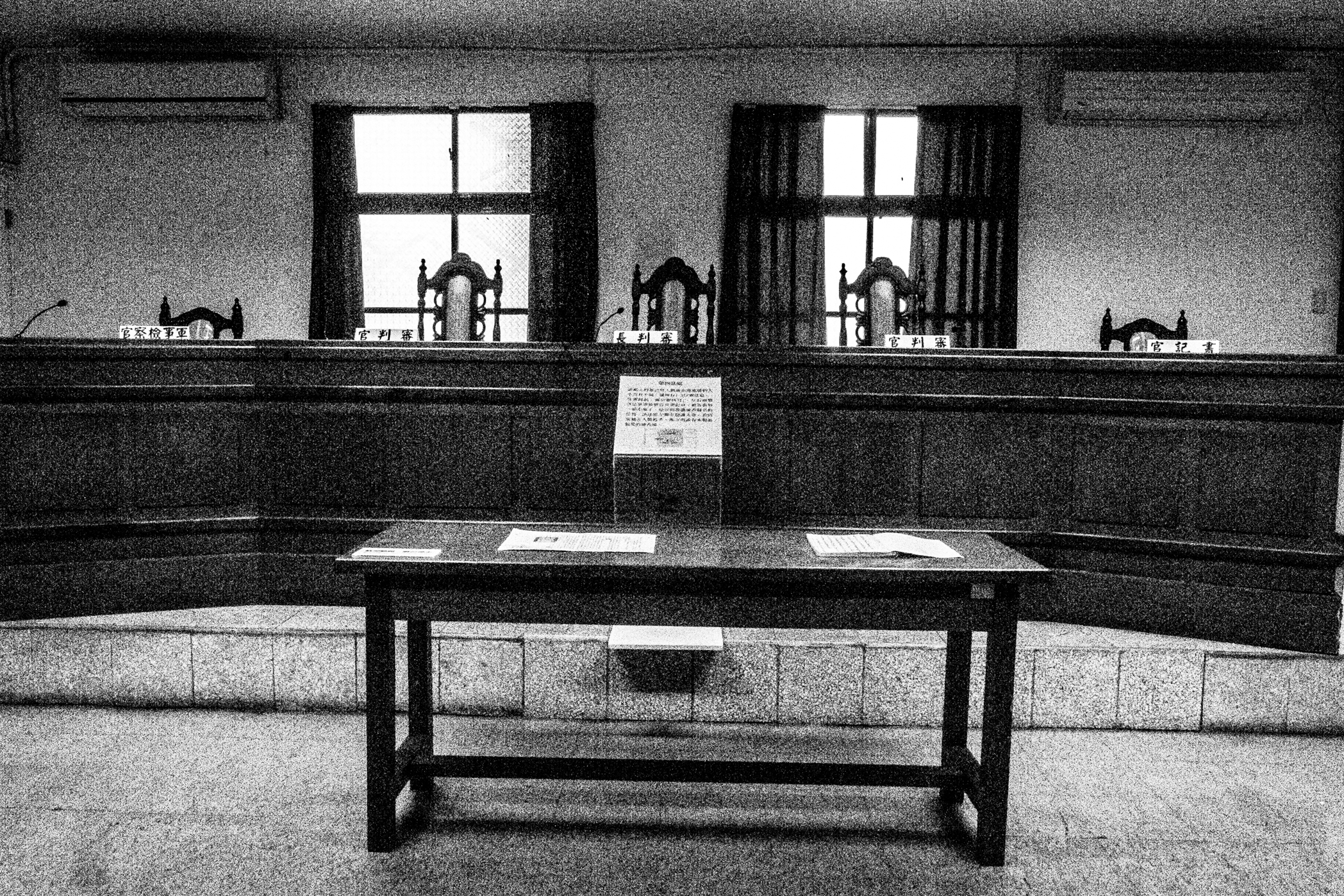

THE JING-MEI White Terror Memorial Park in Taipei is one of the two White Terror sites managed by the National Human Rights Museum. Without knowing Taiwan’s history, this park would look like a quaint college campus from a bygone era, but as the name of the park implies, this was a historical site dedicated to the legacy of White Terror, the very place where victims of White Terror were interrogated, tried, and imprisoned (the execution took place elsewhere, and the site has been demolished).

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Despite its now calm appearance, the historical park has preserved the military barracks, the Detention Unit of the Investigation Bureau, two military courthouses where the defendants had trials, the prison itself, where Vice President Annette Lu was imprisoned, and what caught much of my attention, a special jail unit for Wang Shi-ling.

The museum offers free tours, and I was able to go on one during my visit. The tour happened to be about the prison itself, starting at a building with the unintentionally ironic name of Renai Building (仁愛樓 or Kindness Building). At the entrance of the building, a statue of a xiezhi (獬豸), can be seen facing away from the prison. The fact that the xiezhi, a mythological animal that symbolizes justice—whose horn is supposed to point out the guilty party—is facing away from the prison, might have been intentional on the part of the craftsman who made the sculpture—but no documents exist to prove that is the case. The intention of the artist/sculptor remains a mystery and is something to think about, as suggested by the guide.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Once in the building, it is clear that the system of imprisonment was set up to not only punish but also to humiliate and dehumanize the prisoners. The iron handcuffs were of the type you’d expect from a pre-modern era—the type you’d expect when you think of slaves in chains. These handcuffs, needless to say, are very uncomfortable and easily cause injuries. As we walked through the hall, the guide explained to us that the narrow window near the floor was used to pass bowls of food to the prisoners. This window was designed to be near the floor with the clear intention to dehumanize and humiliate the prisoners—it is as if the guards were feeding dogs.

When entering the gate to a courtyard where prisoners could spend ten minutes to get fresh air each day, we saw that the gate was designed in such a way that there are two doors—one is normal, and the other is a door within the door which prisoners would have to crouch down to enter. This, too, was designed to humiliate. We were able to visit only the men’s prison, as the women’s prison, on the second floor of the building is currently under renovation.

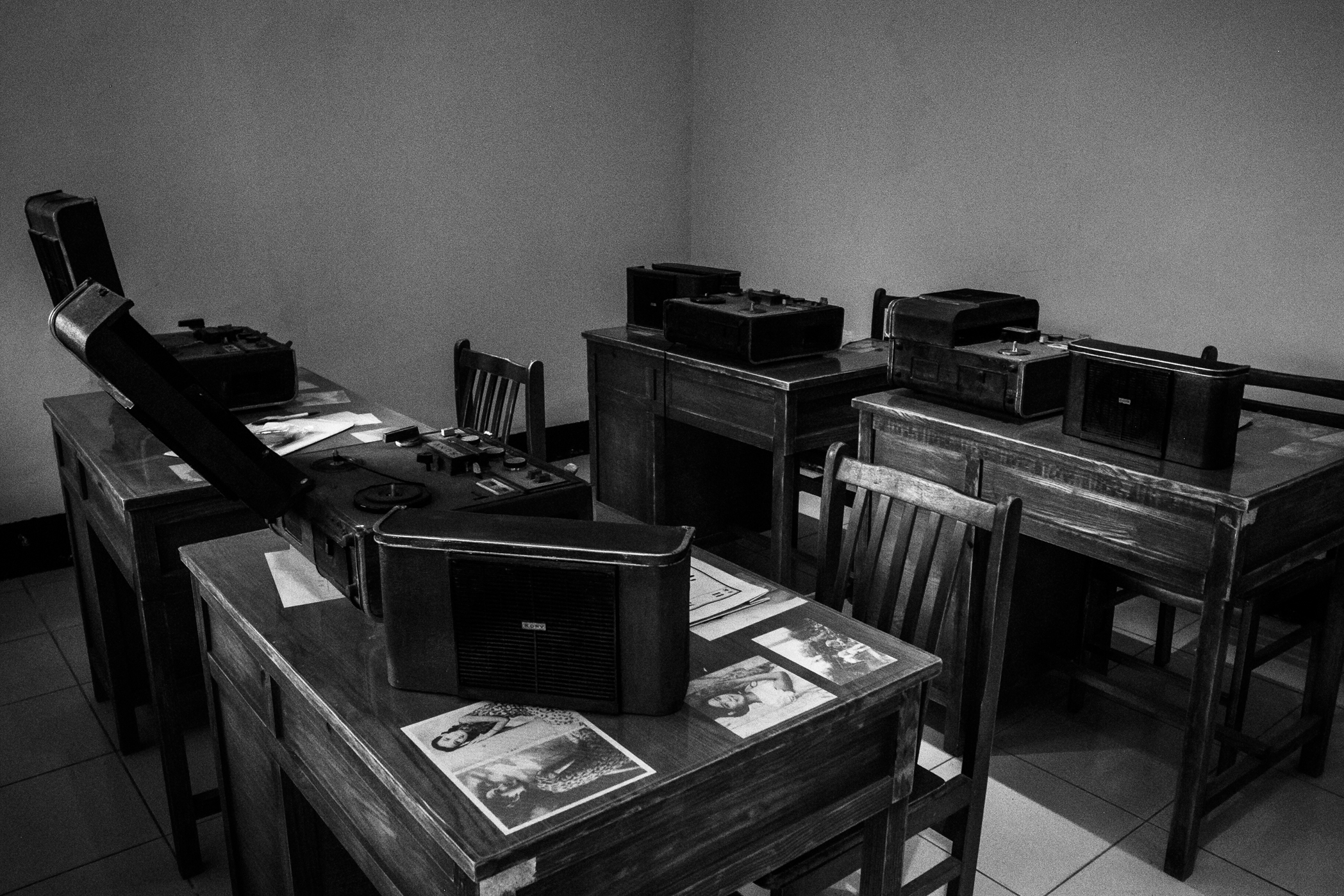

Other than the actual prison cells, visitors can also see the prison’s visitor room and see how conversations between visitors and prisoners were monitored in an adjacent room. Because of this, the prisoners and their loved ones would instead resort to writing on their hands to convey messages. On the other side of the building, one could also walk through laundry facilities where prisoners worked—this prison would take on commercial laundry work and make profits off prison labor.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Not all prisoners were treated equally. Some were assigned privileges, such as the in-house doctor, who was also a prisoner. The guide explained to us that the doctor had enormous responsibility for treating every single prisoner, and at times, prison officials would make the doctor leave the prison to treat their own families. The doctor, in return, received some special privileges in the prison. This relative privilege reminded me of our contemporary times —doctors are assigned a sort of a sainthood in Taiwan, to the point that the next presidential election will most likely have two medical doctors competing for the position. However, the most privileged prisoner was also the most notorious—Wang Shi-ling (汪希苓).

Wang Shi-ling was not a political prisoner like the rest of the population in this compound. Wang was an admiral and also Director of Intelligence at the time of his arrest. He was arrested and imprisoned in connection to the murder of Henry Liu. Henry Liu (劉宜良), wrote under the pen name of Chiang Nan (江南), was a Taiwanese American reporter based in Daly City, California who wrote an unflattering biography of Chiang Jing-kuo (蔣經國). The ROC government then ordered the killing of Liu by contracting gangsters from the Bamboo Union. The responsibility for the killing ultimately rested with the Chiang family, most likely Chiang Hsiao-wu (蔣孝武), Chiang Ching-kuo’s son and Chiang Kai-shek’s grandson. However, Wang Shi-ling took responsibility for the killing and was “imprisoned” at this facility. Wang, to this day, still denies Chiang Hsiao-wu’s involvement. What is clear is that Chiang Ching-kuo sent his son away to Singapore and stated that the Chiang family would pass on continuing its control of Taiwan to the next generation of Chiangs in an interview in 1986.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Wang’s housing unit is not like the rest of the park, to be sure. The living space is larger and much more comfortable than the rooms in the military barracks—it has a bathroom, a living room, and a bedroom—essentially it looks like a room from a holiday resort. Initially, Wang was handed a life sentence, then the sentence was commuted to fifteen years, and Wang ultimately only served six years, living in what many would consider luxury at the time.

Chen Hu-men (陳虎門), another member of the military who was convicted in connection to the murder, changed his name to Chen Yi-qiao (陳奕樵) and was promoted in the military after his imprisonment. He later competed for a legislator seat in the 2018 election under Mingkuotangs (民國黨 or MKT) party ticket. Chen now serves as chairman of the ROC Loyal Comrades Club (中華民國忠義同志會總會理事長), and even supports LGBTQ rights today.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Ultimately, only one person, Tung Kuei-sen (董桂森), served jail time in the US for the murder of Henry Liu, an American citizen. The generous treatment of criminals that are affiliated with the KMT is not surprising, as in Taiwan—in order to make sure that Taiwanese children learn that morally and historically questionable actions, such as murdering someone, should be carried out, these actions were usually rewarded. This is still true today. For example, the current New Taipei City mayor, Hou You-yi was one of the arresting officers of “Nylon” Cheng Nan-jung (鄭南榕), and Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安), the great-grandson of the genocidal dictator and a current legislator, is widely seen as a star of the KMT. What’s even more absurd is that in 2007, many luminaries from Taiwanese politics and entertainment, including Wang Jin-pyng (王金平) , Ker Chien-ming (柯建銘), and Jay Chou (周杰倫) attended gangster Chen Chi-li’s funeral. Chen Chi-li (陳啟禮) was one of the three gunmen who went to California to murder Henry Liu. None of the individuals who attended Chen Chi-li’s funeral suffered any public backlash.

The National Museum of Human Rights is a new establishment that officially opened in 2018 after six years of preparation. So far, the museum is doing an admirable job in presenting Taiwanese history to the public. The role of the museum plays in informing the public should not be underestimated, as visiting these “Sites of Injustice”, is an experience akin to a pilgrimage for Taiwanese people.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

While I look forward to seeing more from the museum, I hope that in the future, the museum will be able to present Taiwan’s history in a more global context, as Taiwan’s historical trauma is not an isolated phenomenon. Specifically, the period of White Terror happened in the backdrop of the Cold War, in the context of America’s proud post-war tradition of staging coups around the globe and supporting genocidal right-wing regimes in the name of fighting communism. Additionally, I hope that these “Sites of Injustice” will not simply be historical time capsules, but rather, as sites of living history, connect the past to the present—I hope that through such sites, we can critically examine the contemporary justice system and the repercussions of historical trauma.