by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Film Still

IN TRANCE WE GAZE (恍惚與凝視的練習), directed by Singing Chen (陳芯宜), proves a nuanced, complex portrait of man’s relation to divinity in contemporary Taiwan. It accomplishes this by working on multiple registers, touching on the many forms that man’s relation to religious worship can take within traditional Taiwanese folk religion.

The film can be seen as having three distinct registers. In the first, a man comments on the difficulties of knowing whether the gods are real or not, knowing that many gods seem to have to do with the fear of death. He then narrates various dreams of the supernatural he has had in the past, including dreams of his dead grandfather or of being surrounded by ghosts. The man narrates this in Taiwanese Hokkien, using a style of narration similar to that used in 2017’s The Great Buddha+.

Film Still

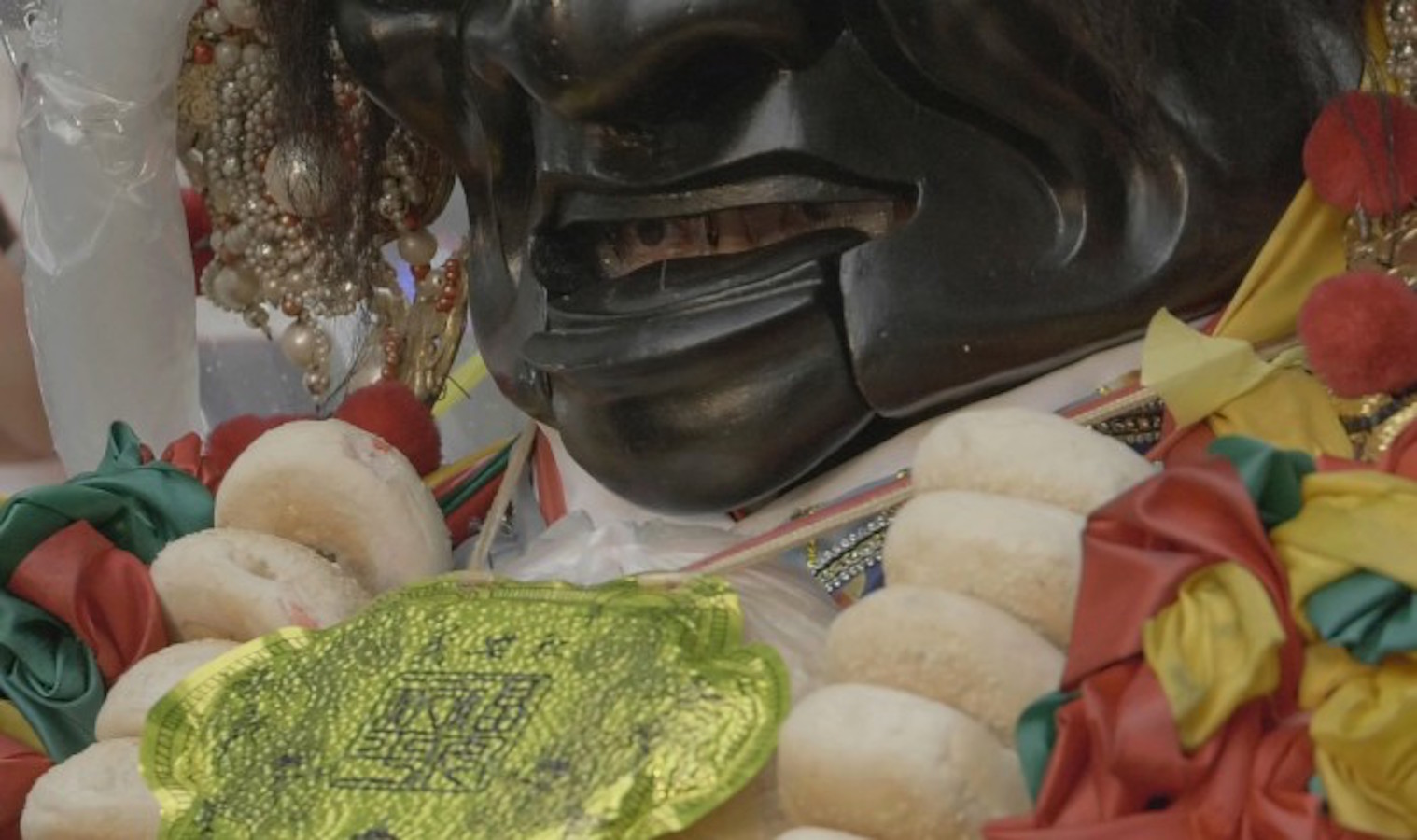

In the second register, which strikes a humorous tone, a man whispers the name of gods and goddesses in the Taiwanese pantheon in Mandarin, along with their epithets and what they are known for This takes place while the film shows statues of gods and goddesses in all their grandeur, alternating with footage showing an expert cleaning and washing statues of gods. This is juxtaposed with the serious tone of the Taiwanese Hokkien narration, so as to add a light touch, as well as to point to where religion can have moments of the comic.

A particularly funny moment is the inclusion of Jesus Christ statuary within this pantheon, though Chen may hope to suggest the syncretic nature of Taiwanese religion, which features Hindu, Buddhist, and Daoist deities alike, and which are of both Indian and Chinese origin. The narration for this second register is provided by well-known Taiwanese performance artist Huang Dawang (黃大旺).

The third register, then, is that of religious awe, with the use of heavy electronic music combined with footage of temple festivals in slow motion and some archival footage of the religious festivals of Taiwan in decades past. By using slow motion and montage to create a sense of awe, the film seems to hope to evoke how the sense of religious awe from temple festivals is derived from the everyday, rather than transcendental experience. Likewise, the film manages to show how religious festivals in Taiwan throughout the ages have variously sought to incorporate elements of technology into them, through its use of historical footage. The results are highly effective.

In Trance We Gaze, then, proves a look at contemporary Taiwanese religion from the perspective of the everyday. Religion is seen from the ground level, with regard to how religion can seem overly mundane and ordinary—or, at other times, it can appear utterly dreamlike. Religion can appear to be divine and awe-inspiring, but this can also be an immanent, rather than transcendental experience.

Film Still

A particularly interesting moment near the end of the film gestures toward the conflict between traditional religious practices and modernity, particularly as advanced by the nation-state. Historical television footage used near the end of the film points to efforts by the KMT government during the authoritarian period to stamp out what it saw as wasteful excesses of the religious. This moment also seems to suggest that the modern state seeks to stamp out religion, because it is a form of experience that is not easily subsumed into modern economic rationality. One can draw parallels with the depiction of religion in The Story of Southern Islet.

The film is a wonderfully composed one, featuring beautiful visuals and archival footage that is integrated quite well into the end product. Not only is image paired effectively with sound and music, but the sound design of the film is an accomplishment, contributing a great deal to the aural experience of the film—particularly when seen in theaters.

In Trance We Gaze proves one of the stronger depictions of Taiwanese religion in past years. The film accomplishes this through what is not only a non-mimetic representation of Taiwanese religion, but a depiction in which form coheres with content. As such, the film is highly worth watching, even if it pushes the boundaries of what some may see as documentary.