by Ho-Chun Herbert Chang

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Shirley Zhang (IG: shooley.art)

I IMAGINED this happening in my late twenties, exactly ten years after high school graduation. A few of us would meet in Taiwan. I had just received my first promotion and at dinner, I’d humblebrag to all my friends. Justin–who would be earning the most–would pay for drinks, then pass out in the car. A few of us would be married, most of us single.

Instead, I found myself back in Taiwan with almost a hundred alumni, reliving experiences that were once my last. Lunar New Year, homecooked meals with grandparents, weekly Karaoke—the routines I’d given up when I crossed the Pacific.

For youth who spend their lives preparing to leave Taiwan, the hardest question is how to come back. The question comes in many forms—why I sit in LA traffic for dinner, when the night market is 5 minutes away back home? Why I should fear of walking out at night? How should I face my parents, who lived along their parents for more than forty years?

I’ve long pondered the life I’d live if I never left. This is the year I found out, on a small island untouched by the Pandemic. In the alternative timeline where we stayed. In the home that I always loved but could only exist in my heart.

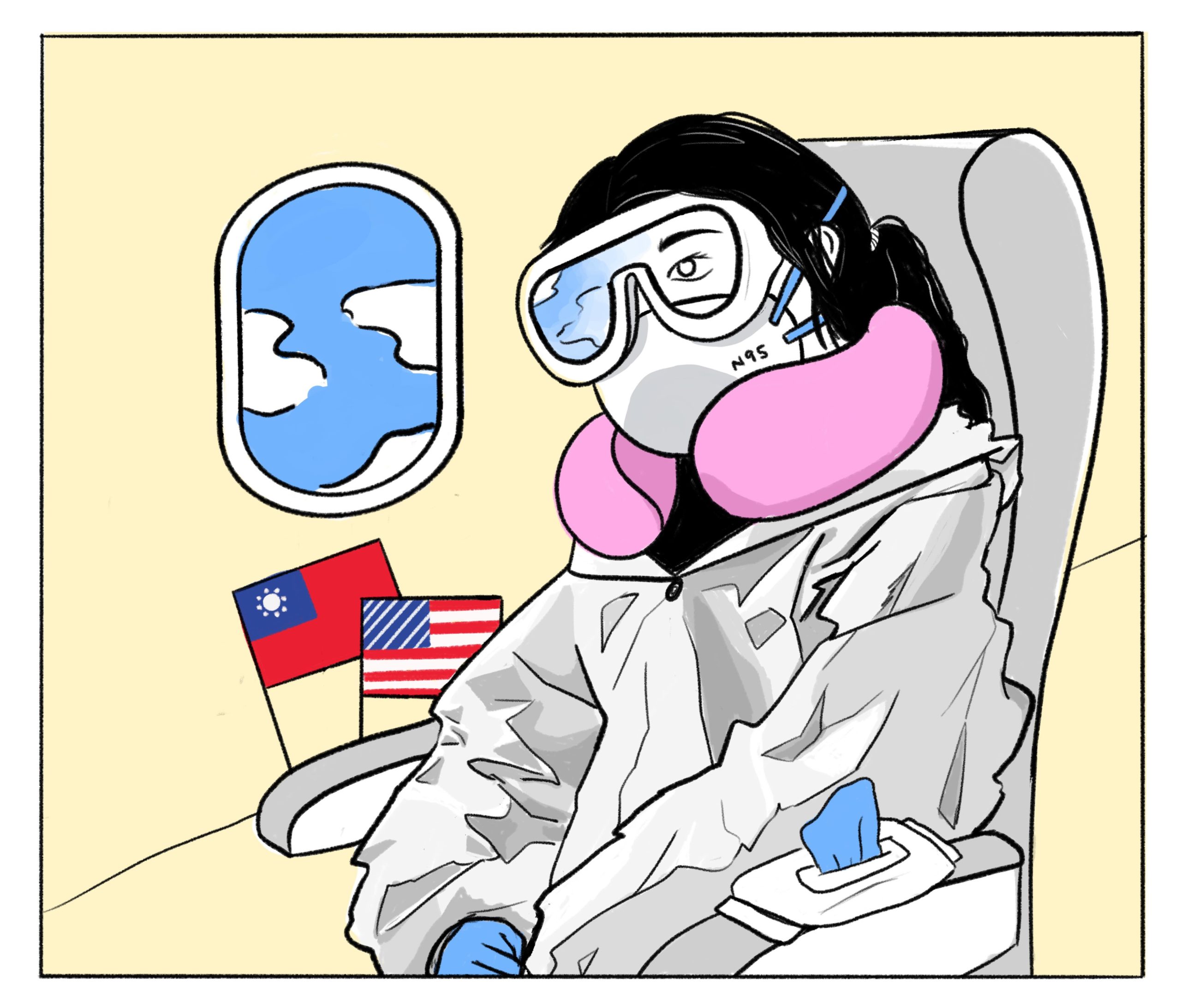

MAY 2020: LAX, and there’s only one place to be—in a long queue for the final flight, destination Taipei. Some students bobble about in hazard suits, but most kids wear plastic raincoats, the cheap, yellow, transparent kind you get for a dollar at 7-11. A sign tells me to declare my health, so I pick up a form, walk past passengers scribbling on the floor, and sign it on my thigh. Waiting while doing, this is an attitude you learn in breakfast shops while fighting hungry students craving soupy meat buns and danbing.

Behind me, an auntie digs for a pen. I reach for my spare, then stop. This pandemic is truly the ultimate test for our social instincts. I slip on latex gloves then offered her a black pilot gel pen. She thanks me in mandarin, and I tell her to keep it. The familiar scent of home returns now. It’s never the cityscape stretching beneath the clouds, nor the taxi winding through familiar roads. It’s the scolding aunties and their cringing husbands at departure.

But for the first time in a decade, I will travel one way. I have no clue how long I would stay, and what it meant for the life I had built in the States.

IT IS A strange ritual we do, calling a place we never expected to return to home. But leaving Taiwan was what I spent most of my life preparing for. After public school for elementary, I transferred to an International School. It never occurred to me how binding this decision would be. Soon, the SATs replaced my national entrance exams, Spanish replaced Chinese, high school volleyball replaced cram school. I was on my way out of Taiwan, as were the 60 graduates our high school produced every year.

Earlier in the afternoon, a girl from my high school appeared on Instagram, driving around the foliage of Westwood in a convertible, which surprised me since she attended college in Boston. Sure enough, she’s on my flight, the only affordable way out of the States.

“We can finally go home!” she tells me. I roll my eyes in agreement. Most of our friends already departed in March, when the lockdowns began. I chat with her as we board, before my 16H takes me away from her 12C. It’s nice to see a familiar face, so spontaneously. Taiwan is surely a small world.

Photo credit: Shirley Zhang (IG: shooley.art)

Photo credit: Shirley Zhang (IG: shooley.art)

My seat is empty when I arrive, but a girl in a UCLA sweater soon joins me. Wearing swimming goggles and a gown of plastic, she’s the most stressed person onboard. Before sitting, she sprays every surface with alcohol—the windows, monitor, front pouch, and my arm on the divider, nothing escapes. I ask if she needs help with her bag, and she grunts as if telling me to shut up, then wipes down every surface again with Chlorox. Finally, she sits, a copy of Rich Dad, Poor Dad clutched tightly with her latex gloves.

The flight attendants are checking seatbelts when her mother suddenly calls, to remind the girl to change out of her skirt.

What if I suffocate! The girl yells back. Then I’ll die and you’ll never see me again. She aborts the call and her mom rings again, asking why she hung up. The attendant wisely skips our row, and I almost laugh. Almost, because the anxious weight in her voice feels heavier than this steel crane bound across the Pacific.

This weight is felt by every one of us. The country our parents believed to epitomize progress and opportunity crumbled after rejecting health practices we’d learned in kindergarten. We travel alone, but are united in our risk calculus. if we had to die from COVID-19, it sure as hell wouldn’t be in the United States.

THE INSTRUCTIONS are like a video game’s tutorial mission. Upon touch down, make your way to the Quarantine Taxi. The Taxi will then transport you back home or a quarantine hotel. For two weeks, eat and sleep alone. Speak to no one.

I pass through customs at 6 AM and my taxi driver, a middle-aged man in brass science-teacher glasses, agrees to drive me down the island for the price of $85. He douses me in a fine mist of disinfectant, and we are off to Kaohsiung, a port city 190 miles down south. As we merge onto the highway, I call my parents to put in my order for a danbing breakfast. First things ought to be first.

Around Miaoli, we pull into a rest-stop, for me to use the restroom and my driver a smoke. I should be quick, but I can’t help but stop. Everyone is walking around normally. After social distancing neurotically in the United States, the crowd’s ignorance toward me, who could very well be Taiwan’s newest case, is unpleasant. But this invisibility is familiar as well. The feeling of being Taiwanese but not Taiwanese, observing both worlds but belonging to neither. My slow pull away from public school in high school returns in a haze.

I slap my face with water. It’s too early in the morning to contemplate so deeply. Back at the car, the taxi driver sucks hard on his cigarette. He leans against the sedan in striped Oxfords and dark suit pants. Seeing me, he waves his cigarette and asks if I was hungry.

“This guy hadn’t had a Taiwanese sausage for two years,” he began, smoke fuming from his nostrils. In the dewy morning sunshine, it looks almost healthy. “He rushed into the food court without telling me. That was not ok, so if you’re hungry, just let me know and I’ll get you something.”

What a stand-up guy. I’m moved but I shake my head. After squeezing back into the cab, he tells me about “delivering people” through winding mountain roads. Young women have it worst. Trips are eight hours and as night falls, the only rest stop is the shrubbery by the road.

On the highway, the Taiwanese countryside gushes by like liquid. Scrap metal cover small sheds, rice paddies stretch into the horizon where the central mountain range juts out lazily. The humid sunshine lacks the ephemerality of Los Angeles afternoons, but makes the air more tangible.

At 9 AM, I arrive in front of my apartment. My parents wait with my grandparents, who hold a bag of danbing just like I requested. When my grandma comes forward to hug me (a behavior I had “Americanized” into my family), I step back quickly. I could not live with myself if I gave her COVID-19. She looks shocked and slowly comprehending the severity of COVID-19 in the United States.

Still, I see their beautiful smiles behind their masks. Careful that our fingers did not touch, I collect my long-awaited breakfast and keys to the apartment. And with that I enter my monasticism.

MY QUARANTINE begins uneventful, if not a little extravagant. My favorite Japanese diner and family friend sends me bentos of my favorite dishes. Slow-grilled salmon collar, torched flounder nigiri, unagi wrapped in tamago— after four months surviving on onions, it’s downright Michelin.

At 9 AM, the health and sanitation bureau calls. An elderly woman asks if I have any symptoms and if I’m getting enough to eat. When I hear her uncertain Mandarin, I tell her in rusty Taiwanese, more than enough. Like my grandfather, she seems more comfortable with Taiwanese. For more than a week, I wake, answer the phone in Taiwanese, eat good food, read, and sleep.

It happens on the tenth day, after dinner. Intense nausea, fever, and a dry cough. The bedsheets feel starchy and after staggering to the restroom I spewed my dinner into the toilet. In 10 hours, I somehow develop all the symptoms of COVID-19. I resign to a night on the bathroom floor and in the morning, I call the bureau before the elderly woman can call me.

They tell me to sit tight. Within minutes the Doppler shift of an ambulance grows in volume and vanishes outside my apartment. I stumble to the elevator, and as I shut my apartment door, I recall all those times I pretended to be sick, to skip school. It feels like karma.

Outside, an EMT waits for me in protective gear. I muster an energetical greeting and he leads me into the ambulance, closes the door with a practiced jerk and slide, switches on the siren, and accelerate d. I cling desperately to the seat. The 10,000-pound toaster oven hammers down the street and tosses me like a salad, and all the while I wish I had just stayed home.

When we finally arrive, the EMT shoots me a look of pity then points me to empty plastic stools on the pavement. I chose the one furthest in the shade, and he leaves with a quick salute.

Twenty minutes pass. My T-shirt grows moist from the summer heat, but since it’s my first time outside I experience a strange moment of serenity. Across the streets, shops seem to sprout from my childhood. Open veranda storefronts that aren’t sure if they were in business, or not expecting customers. Stacks of yellowed newspapers cover cabinets that long exhausted what they were displaying. An ah-bei (uncle) sits in front of an electric fan, bare feet kicked up and smoking a cigarette. Rusted metal bars protect second-story windows, inherited from past decades of petty crime. Clothes flutter on the balcony, drying in the same sun baking me into oblivion.

It takes me a moment to comprehend the store signs, which jolts me awake. Wedding Makeup and Bone Collection. These shops provided funeral service by the hospital, tasked in sending loved ones away as they were beautiful on their wedding.

The view from Ming-Shen Hospital, Kaohsiung. Photo credit: Ho-Chun Herbert Chang

In this moment, I am a foreigner learning about my own culture, about the business of death across this tarmac river. In discovering this unknown part of Taiwan, my surroundings sharpened around me once more. The plastic chairs scattered on the sidewalk, the grid of electric tape. The weathered concrete of the old hospital. Everything stands in contrast with what I’ve heard about Taiwan in the US. Wired magazine framed Taiwan as cyberpunk, fully embracing cutting-edge contact tracing as the gold standard of COVID-19 response. But behind the glamor and hype, reality is much simpler. Taiwan aggressively closed its borders when other countries would not, due to Taiwan’s contentious history with China and experience during SARS. Public cohesion is strong; backlash against economic loss was muted.

I shiver despite the heat. If the virus were to arrive upon these shores, I suspect this island nation would be just as frantic and under-prepared. How many people would be sent away, in their wedding make-up?

As if on cue, an overworked doctor comes out from the ER, hair disheveled, and reminds me I was not there for sociological inquiry. He swabs my mouth then sends me into a pressurized chamber. A portable X-ray is called in, which presses me against the ICU bed. For a moment, I am the dough inside a medical waffle machine.

Next steps are a blur. I am released, and after paying 8 dollars for the ambulance ride they drive me home, with the sirens off.

Two days later, I tested negative despite ongoing nausea. By the principle of exclusion, my mother concludes my seafood congee must have gone bad. Within 24 hours, I leave my apartment, and with my first steak in four months my quarantine draws to an end.

SUMMER PASSES in such a repetitive fashion. I wake up, analyze data, play tennis with my dad, cook with my grandmother. I sync my rhythm with the life I’d led, with my body in Asia but my mind in the States. I took this dogma so seriously that I’d unconsciously avoid cafes where my friends appeared, on social media, as if to partition my past and peculiar present.

That had been the promise of college, to kill the parts about myself I didn’t like, and keep the ones I do.

However, with Covid, there is no end in sight. As summer vacation draws to its end, a high school classmate asks me to play volleyball. A recent UC Berkeley graduate, David is caught between college and veterinary school. I work at our high school, David tells me, Middle schoolers in Biology class. Those little jerks. I remind him we were much the same. I once stuck a wad of gum in his hair, en route to a sports tournament. Forced to shave his head, like a little boy, he told his mom he’d kill me at school. A year later, we became friends as if my sins had been forgotten, went through puberty, co-captained varsity volleyball, until college did us apart.

Haikyuu!! anime

He picks me up Sunday after lunch. As he drives, he speaks of our one lingering regret. In our senior year, we traveled to Shanghai for our volleyball tournament. After battling through team after team, we lost the final to the home team. Two months after our loss, Haikyuu—the popular Japanese volleyball anime— spread around the world. We could only wonder if watching the show together would have helped us win. Volleyball is, strangely, to Taiwanese and Japanese youth a Bildungsroman rite of passage. Sociologists posit it’s because teamwork is crucial, a value essential to Japanese society and hence Taiwan, a vestige of their colonial influence.

My high school was the same way, built into the 60-year-old colonial carcass of an elementary school. Barbed wires curled atop a concrete wall, thorns long rusted with age. Old and underserviced, it was rebuilt, grounds-up, after our graduation. As David pulls into the school, the new school in all its glory emerges. Four stories of airy, open halls, complete with LEED-certified Scandinavian sensibilities. Seminar rooms better suited for parliamentary meetings than teaching kindergarteners. We walk past a dance studio that oversees a full-length swimming pool, state-of-the-art science benches, integrated Apple projectors, before finally arriving at the indoor gym with gleaming hardwood.

By 2 PM, 30 alumni have shown up across seven class years. Some faces have grown more rugged, some more mature, and for some, the impact of Freshman 15 was evident.

David, as a staff member, is the host. Once he rolls out the balls, small friend groups form bumping circles on autopilot, in Déjà vu as they had more than a decade ago. Soon, teams form by natural osmosis— triplets of friends link to form units of six.

The first game runs as one might expect—like the dumpster fires in mandatory PE class. Bodies crash, balls fly everywhere, rarely do we string together a full bump-set-spike.

Once it ends, I start a hitting line by offering to set. It’s the most natural to dissolve existing teams, since attackers must communicate with the setter to present their best self. The setter is thus an attacker’s best wingman. Do you approach with a curve? How high do you want the ball? For Ching who unconsciously approaches straight on, I give him an arcing ball with space to land. For underclassman David, who likes to run early, I set with a faster pace.

Over the next few weeks, trust builds and the teams fracture. Sunday volleyball becomes “a thing,” the hardwood our church. More alumni attend and we run two courts.

What surprises me most is how easily we became friends. By living in the United States, differences that seemed unbridgeable during high school—grade level or social cliques— are subsumed by our shared marooning. And stranger than my new friends is playing with my old ones. Now managers of their family business or emerging artists; pre-professional bankers or slogging through graduate school, we would never intersect in the United States. On a college campus in the US, we’d be labeled woke snowflakes or econ snakes, insoluble identity tags that prevented an afternoon at the beach. But they were exactly these—labels we only picked up in America. Back home we were the same kids that graduated together in 2014.

New routines form. Early mornings and late nights, I’d groggily touch base with colleagues in the States. Lunch, meet up with a close friend, probably at the local Shi-Shen Tang shop. Monday night, badminton with my classmates. As much as I try to resist its gravity, I am drawn into the orbit of my past life.

FALL COMES as it always does— when you can stand outside without sweating. My grandmother announces she bought tickets to a classical music performance at Kaohsiung’s new music hall, and my uncle would be conducting.

The idea of publicly listening to anything is so alien that at first, I don’t comprehend her. But once I do, I harbor only anticipation as this would be as much an architectural adventure as a musical one. Designed by the same architect as our school, the new music hall has made rounds in architecture magazines in Asia.

We drive into a massive complex melding Scandinavian wood-and-polymer with Tadao Ando exposed concrete. Ushers take our temperature and log our presence for contact tracing. They wear plain black T-shirts and loose pants, stylistically similar to your typical Muji mannequin. In the hall, polished wooden seats glow in tangerine, the observatory decks in caramel, the perforated walls in milky beige. The stairs, accented by strips of diffuse gold, ascend panoramically across three levels. Finding my seat feels like wading through a warm canvas.

Only after I sit down do I wonder who was performing as, in addition to the orchestra, my grandmother mentioned three violin soloists. I wonder because our borders were closed to all except citizens of Taiwan. In my narcissism as the audience, I forgot musicians are also people subject to the same quarantine, jet lag, and visa bans.

I reach out for a program, then stop myself. I don’t need to know the violinist, or if they went to Juilliard. The music could speak for itself. To my surprise, a familiar face emerges with the thunderous applause. It’s Ray Chen, beyond his numerous international accolades, he achieved internet infamy through YouTube. He was born in Taiwan but soon moved to Australia.

Like that distinct movie effect where the camera lens, I feel fractures in my memory, contradictions of existing schemas. I have grown so accustomed to expecting the Itzhak Perlmans, Hilary Hahns and Sofia Mutters playing on stage it somehow never crossed my mind that the performers could be Taiwanese or of Taiwanese descent. A stage full of Taiwanese, with an audience bearing the same face and name feels casual, communal, intimate.

Chen displays pristine Pizzicatos, and my uncle conjures up a lively Stravinsky. In the great expanse double basses thrummed like Timpanis. Halfway through the third movement, I spot a pale face across the hall—a high school friend, decked out in a T-shirt and lounged back. From volleyball, I knew she was an artist based in the UK, until she escaped Britain’s spiral of infections and put her career on pause.

Ray Chen Performing in Wei Wu Ying. Photo credit: Ho-Chun Herbert Chang

Intermission. My friend catches my eye and waves, and I am overcome with a double vision. In the afterglow of the spotlights, we stand on a stage of our own. The expectations our families had for us are the same as the musicians on stage. Each soloist is that neighborhood kid who had left the island, procured their western degrees, became the role models who mastered music irrelevant to our own national history.

But unlike the violinists on stage who spoke in a universal language, the curse of living in the States, was that for every step you took forward, was an irreversible one away from Taiwan. Our music will always have an audience, every ridiculous Paganini arpeggio seemed to say. We’ve found a way back here, a way to live, What about you?

I REMEMBER a conversation I had during volleyball, over bottles of Pocari Sweat, with the most recent high school graduates. I asked how they were spending their gap year. They told me they just got their scuba diving license and lounged at the beach. Life was good. Still, they couldn’t wait to leave Taiwan and live in some historic city.

I had felt the same way, those years ago. New York, Boston, San Francisco, Edinburgh, London—there was something about these cities that insisted to newcomers to consume the city’s essence, to be the city, and in doing give up part of themselves.

What do you look forward to the most?

“I can finally wear whatever I want,” a soon-to-be New School student exclaimed.

Could you clarify?

“Well here, you kind of have to dress worse than you want,” he replies, “Or else you get judged? There is always someone watching.”

Social cohesion is a double-edged sword. In Taiwan, if I dropped my wallet someone would hand it back to me. I feel comfortable leaving my laptop in the open. That same care is also a sterilizing gaze, an unhealthy weight that modulates what you should wear, can wear.

IT’S DAVID’S birthday, and we’re on our way to the staple of Taiwanese life. Karaoke.

For context, these aren’t karaoke bars in Europe or the States. These are Macy-sized box stores with hundreds of rooms, where friday-night salary workers, high school students with fake IDs, drunk college kids, and Taiwanese of all walks gather to belt.

The place David booked isn’t the best—lyrics are projected onto a small nook on the wall, and microphones are tethered to the walls instead of wireless. A small disco ball underwhelmingly spins from the ceiling, and darkness obscures the cheap furnishing and liquid stains. The room reminds me of where a hostess was murdered in a classic Yakuza flick.

But what can we do, he only has coupons for this place.

I didn’t do much karaoke in high school. But once in college, I held many sing-offs with the Taiwanese Association. Singing mandopop, abroad, had a different valence. Cheesy Jay Chou songs weren’t just an exercise of sharing our background, but a monthly reminder of who we were. But as a result, my personal catalog remained locked to my high school playlist.

We order fried burdock, the cheapest beer, and hot tea to soothe the throat, before finally snuggling into flaking leather. With us is David’s girlfriend and a couple of high school friends. Bodies on auto-pilot, they tap away at the touch-screen, queuing songs. For these pros, maximizing coupon value took precedent over politeness. By the fifth song, I realize I’m out of my depth. I don’t recognize a single song. I forgot that karaoke is just as much a social skill as it was technical, demanding not just attention to chart-toppers but consistent practice in the shower and the car.

Strangely, these songs didn’t sound like Taiwanese pop that I knew from memory. Ballads are infused with a distinct independent edge. Street food has woven its way into rap and trap, slaps hard. Funky disco lines from the 80s are everywhere. It’s as if I’m understanding the words but the underlying culture seems to have shifted in my absence.

Finally, my Jay Chou song appears. Wow, this song has been sung to shit, a friend snorts. She says this with no ill-intent. I am hurt, nonetheless. I finish with a round of sympathetic applause and pass the mic to June who also returned from abroad. With also a limited selection but encouraging friends, she works her way through Avril Lavigne’s first album. Halfway through “Complicated,” it became clear that those who returned early, to continue family business, sang the top hits like well-trained performers. The recent returnees resigned themselves to Lady Gaga and Backstreet Boys.

I find a temporary solution. Near the end, I sing one of those timeless hits my mother used to listen to on the radio, now erased by YouTube’s algorithms. This garnered approval, and in it, a desire for redemption.

As the weeks pass, I find myself on Spotify’s Taiwan Top 50 frequently. A song appears one day and immediately enraptures me. Titled “Your Name Engraved Herein,” it’s the theme song released ahead of a movie of the same name. I listen to it in the metro and while in the car. Once the film premiered, the song achieved top rankings in Hong Kong, Singapore, China, and eventually made its way to the New York Times. The plot is simple, following the friendship and eventual romance of two middle school boys. Both in the marching band, they develop feelings for each other, in a time when this is obviously taboo. To mirror this, simple guitar chords pave way for the soaring melody of a French horn.

The lyrics that come shortly after, that remain constantly in my mind, capture taboo perfectly— even breathing feels like an indulgence. I sing it in our next karaoke and end up with tears in a room smelling of smoke, whiskey, and fried chicken. Taiwan, which I remembered as pragmatic to the point of conservatism, had let loose like a friend I could relying on drink with after work, and listen to my internal dramas.

This was the first time Taiwan felt like an alternative timeline. A life where I could grow old with my childhood friends and see my parents weekly. One where we’d never set off for the States. One that was possible.

I’M SURE you’ve heard of the Ship of Theseus, the thought experiment which ponders the question: once the components of a ship are completely replaced—from the deck to the oars to mast—is it the same ship? Visits back to my high school are very much the same. Teachers and students come and go, but clubs and classes remain. Nerdy kids spearhead decathlon, and their extroverted friends chair Model United Nations. There’s always a K-Pop dance crew and musical performance group. Same clubs, different faces.

So, is it the same school?

My answer to this is no. High school was indistinguishable from the faculty. Mr. Oddo was one of these unnegotiable presences. Coming to Kaohsiung after 30 years teaching in New York, he was the model of a high school biology teacher. To get students interested in marine science, he took them diving in the Maldives. He wrote no less than forty college recommendations every year. He was also my soccer coach. With no field, we practiced in a public parking lot and often left with shit on our shoes. With no children, every one of us felt like one of his kids. So, when he left to teach in South America, not only did he leave an irreplaceable hole in the science department, but my reason to visit.

High School is a metaverse. Photo credit: Double Identity, 1967 DC Comic

However, unexpected faces took up the mantle. Like David, my ex-girlfriend works part-time at our school and teaches mathematics. We go way back. I had known her since third grade, shared our middle school years, went to prom together. In my sophomore winter, we broke up amicably in Boston. Staying friends has been simple, so long as you limit what you speak of.

With a major in music and talent for getting along with anyone, she began singing A Capella with three seniors at our high school. She texts me one day, if I was interested in beatboxing. With only experience in spontaneous improvisations and making recordings for my linguist friends, I said yes. A week later, I arrive at her house as I had in high school, when we played sonatas on the violin (me) and piano (her). I was back beside the grand piano I never thought I’d see again, the living room I’d never return to.

She pulls up, and three seniors spill out her SUV. They say hi then lounge on my ex’s sofa, completely comfortable. The first practice runs as expected—looking over the sheet music and listening to the original performance. But with no expectations what friendship with high school students would be, I feel surprisingly comfortable. Here’s what I learned about them in the next two months, over McNuggets, IKEA meatballs, and our weekly practice:

- Daniel (tenor/bass) is interested in Taiwanese politics, wants to study political science, already dates college girls. Great voice, sang for the United Nations.

- Sandy (soprano/alto), equally book smart, tech smart, and street smart, is someone that can learn anything by YouTube tutorials.

- Annie (alto), the most chill, is as good a dancer as a singer, and probably spends too much time chilling at the beach.

We perform two songs from Pentatonix, one for Halloween, one for Christmas on the last day of school. After our last performance, my ex goes to a faculty meeting and I somehow find myself chatting in a circle of seniors, who will enjoy their winter break in cafes. They will be submitting their college applications. I ask the most natural question: what they wanted to study. Half-expecting non-commit eye-rolls, a flurry of precise answers emerged: molecular chemist, doctor; lawyer, political scientist. Strangely, the contours of their futures are much more visceral than my own, seven years ago.

This is only one of the differences. There is a greater presence of Mandarin over English on campus. Whereas we were taught to repress our political preferences growing up, they seemed comfortable in it—be it gender identity or views on Taiwanese politics.

Spiderman and its many renditions pop into my mind like a time-capsule. Our high school experience was the millennial, Tobey Maguire version—crappy cafeterias, self-obsessed teenagers whose primary objective was popularity. Kids now grow up in the Marvel, Tom Holland version. Brains are requisite for popularity and high school internships are sexy. High school seems like a healthier place, at least one where I’d enjoy, one where I could be myself more comfortably. Students today have a greater view of what lies beyond high school, yet simultaneously has a clearer picture of what Taiwan means to them.

As they pile into their taxis, I hope they remain friends. People inevitably move on. Wedges crystallize even if there are limits to what we can talk about. But in those listless evenings alone in a new city, these are the people you want to ask to the nearest diner, just to be alone together.

BY FEBRUARY, I remember Christmas and New Year’s mean little more than end-of-year discounts. Because in February, factories no longer spew smoke. SUVs pack the highways, loaded with children, en route to hometowns. Restaurants cater to family, not customers. Lunar New Year arrives.

I spend Nian-Ye Fan (the year’s final meal), in a mountain cabin shared by my extended family. We eat home-cooked meals at our mahjong table, centered around the local specialty—clay pot chicken. Free-range mountain fowl are tied in urns and slow-cooked. I slip on transparent, plastic gloves to pick the loose meat, while ignoring the carcinogenic decomposing plastic.

Day two of the New Year, I visit my mother’s family. On the way I hear karaoke in Taiwanese in the streets, which my grandmother disparages for being too loud. My father’s family emulated the modernist Japanese family, with valued gentile reservation. My mother’s, from Taichung, is a bit more traditional.

It’s been a decade since I’ve felt this quiet source of cabin pressure.

Last time was in high school. I returned early to find my mother cooking. Our stereo usually played classical music but, on that day she was listening to a Taiwanese song. And when the song ended, unconsciously, she switched to Saint-Saëns.

STRAWBERRY SHAVED ICE with my grandparents one winter evening, and as the news about Taiwan’s vaccine embargo gurgles in the back, my grandfather refers me to my father. It is a slip of the mouth rather than memory, but his mistake opens the past, and he complains about the same shaved ice he ate all those years ago at the 1967 Tokyo Expo.

My grandfather was a rising architect who helped design Kaohsiung’s harbor, the port that propelled Taiwan into economic relevancy. His dream was to study abroad in Japan, and following the success of the port, his chance came. The government deployed him to Japan, entrusted to learn from imperial engineers. After saying goodbye to my father, aunt, and grandmother, he boarded one of the world’s first Boeing 747s, visited Korea en route, then touched down on the Haneda airstrip.

He was assigned to the Fukushima Harbor. Fearing radiation after the war, the Tokyo elites lobbied against land routes for uranium, necessitating a port to receive the radioactive ore. Following the 2011 Fukushima disaster, they may have a point. He spent a few weeks there, inspecting the structural design. Right before his trip ended, his hosts brought him to the Tokyo Expo where he bought gifts and treats, including the overpriced strawberry shaved ice. As he perused the gift shop, a 3D world map caught his eye. Embedded with flags, delicate figurines popped out at the press of a button. He bought it for his kids on the spot.

In his hotel room before his flight, he made sure to rip off the flag of the Chinese Communist Party. Any reference to them would mean lifetime in prison. But when the customs officer searched his bag, they held him back.

“Isn’t this the flag of the Soviet Union?”

“What does Taiwan have to do with the Soviets?” he asked politely, “Don’t textbook maps contain the Soviet flag as well?”

The unyielding officer confiscated the toy. While ire may sometimes fade overtime, his indignation lingered weeks after the confiscation, so much that he drafted a forceful letter to the Customs Bureau. Don’t maps in textbooks also show the flag of the Soviet Union? This was not the treatment I expected after representing Taiwan in Japan.

Weeks pass. His doorbell rings one afternoon and two men stand outside, hard-boiled and suited. They were KMT, the occupying mainlanders whose officers enforced the island-wide martial law. My grandfather asks my grandmother to make tea while he quickly combs back his hair (as he does now) to greet them, then offers them a seat at our salon. One of the suits unclamped his briefcase, reached in, and returns with the toy map. He places it between them, and my grandfather stays still, unsure if he has permission to reach forward.

The other suit says sorry, then dips his head to bow—courteous, but not apologetic. My grandmother serves them tea, they chat about his time in Japan, before they leave.

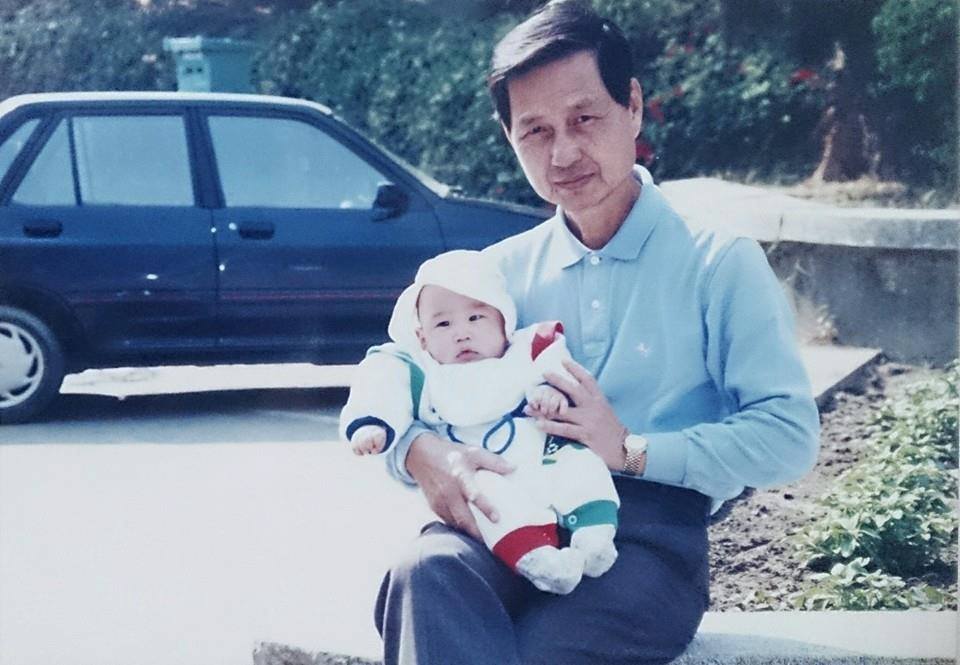

When recounting his memories, my grandfather reminds me of a novelist, showing; never telling. He articulates these stories in passing as if they happened last weekend, his tone meticulously casual to concealing hyperbole. But at 90 years old, the line between exaggeration and grace invariably blurs. He knows it, knew for a long time.

The summer after my first year in college, at our mountain cabin. My grandmother picked vegetables in the garden, my father parked the car, my mother and sister strolled on uneven cobblestones. It was an ephemeral pocket of silence that existed due to the unintentionally coordinate of absence.

Grandfather and I, 1996. Photo credit: Ho-Chun Herbert Chang

I was reading a novel on the porch when my grandfather sat down next to me. In place of his usual casual dignity was a pensive expression, directed toward the betelnut trees speckling the mountainside. He turns to me suddenly, then taps his head.

“There are many things I should tell you. While my mind is still clear,” he says. His tone is matter-of-fact, thoughtful but not sentimental. Every summer since, every game of Go feels like a test of cognition. The delicate control over his emotions has weathered away, slowly, surely, gracefully.

For this, I am unapologetically grateful for the time afforded with my grandparents, by the pandemic. Never would I have had the chance to hear what they were once reluctant to say, lest I judge their delightful past insipid. Never could I sit at the dinner table, and learn how Japan was to my grandfather, as America is to myself.

MR. ODDO passed away on a spring Tuesday. I hear it from my high school principal, who tells me Oddo was not feeling well, tried to contact the embassy in Myanmar, and en route to the hospital he collapsed. Vaccines are right around the corner. It is a wake-up call, that our time in Taiwan is due to a global pandemic.

I write about him all night, trying to distill every memory I had of him. At 5 AM I toss it online, sleep, and wake to the messages of his past students, each sharing their own stories of soccer practice and biology class. We hold his memorial at our school in May, two months after his passing. We dress in format attire, a tradition from our varsity soccer days. We recall the public encouragement from class and the quiet moments over dinner. We act cheerful, the way Mr. Oddo would want us. State-side, hundreds of students over his illustrious 30-year career hold their own remembrance.

As the service ends amidst the new courtyard, among the last members of students, faculty, and staff who know Mr. Oddo, I feel something come to an end—my time in Taiwan, and the high school I could always come back to. The gears of the academic year churn forward, unrelentingly. Universities declare their in-person fall plans. The a capella kids have gotten into college— UMichigan, and two to UC Berkeley. The kids at weekend volleyball dwindle, as they return abroad. Ray Chen, the violinist, was last seen in Hawaii on Instagram.

Soon, the question comes as it did a year ago, while browsing Google Flights. Should I book a one-way or a round trip?

It’s clear, now, what I feared was falling in love with life in Taiwan. Because life on this island—simpler and grounded—would betray the life I had planned, what my family built for me. It had always seemed like a choice between the two. Moreover, if this year appeared like a fantasy, it’s because it is—never again, hopefully, will we need to maroon ourselves in Taiwan to avoid a pandemic.

However, the pandemic has shown me a way to carry Taiwan with me abroad. For the longest time, being Taiwanese abroad was inextricable from political opposition with China. Identity was an exercise of gestalt, defined by who were weren’t. But the late-night indie flicks, the stories of my grandparents, and the budding pride and wisdom of high school students, these are all tangible kernels I can bring across the Pacific. With distinct artifacts replacing our political opposition, it’s possible to be what we are, rather than what we are not.

And in this sense, high school is no longer just a time to look back upon, but my community abroad.

So I book a one-way, but also write a to-do list: text my grandparents and parents on LINE. Ask in Taiwanese how their day was. Track Taiwan’s Top 50 Playlist, and practice in the shower. Read the news and Taiwan’s new suite of science fiction, and road trip with high school alumni. Whenever possible, fly back to steam fish with my mom and play tennis with retired uncles in the park. Burn incense and sweep the tombs of my great-grandparents, in the small pineapple field that is our family grave. Mahjong in the mountains with my grandparents.

I’ll carry this reunion for years to come, this year when Taiwan moved as the world stood still. It’s a reminder that I don’t need to be a visitor. It’s fine being a kid of Taiwan, slowly finding my way home.

Ho-Chun Herbert Chang is a writer and Ph.D. candidate studying depolarization in social networks. He recently covered the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2020 USA and Taiwanese Elections, and the Floyd protests, and his work has been featured in Scientific American and the New York Times. He received his M.Sc. in artificial intelligence and majored in math, social science, and creative writing at Dartmouth college. He is a finalist for the 2022 Guthman Musical Instrument Competition.