by Minsu Yoo

語言:

English

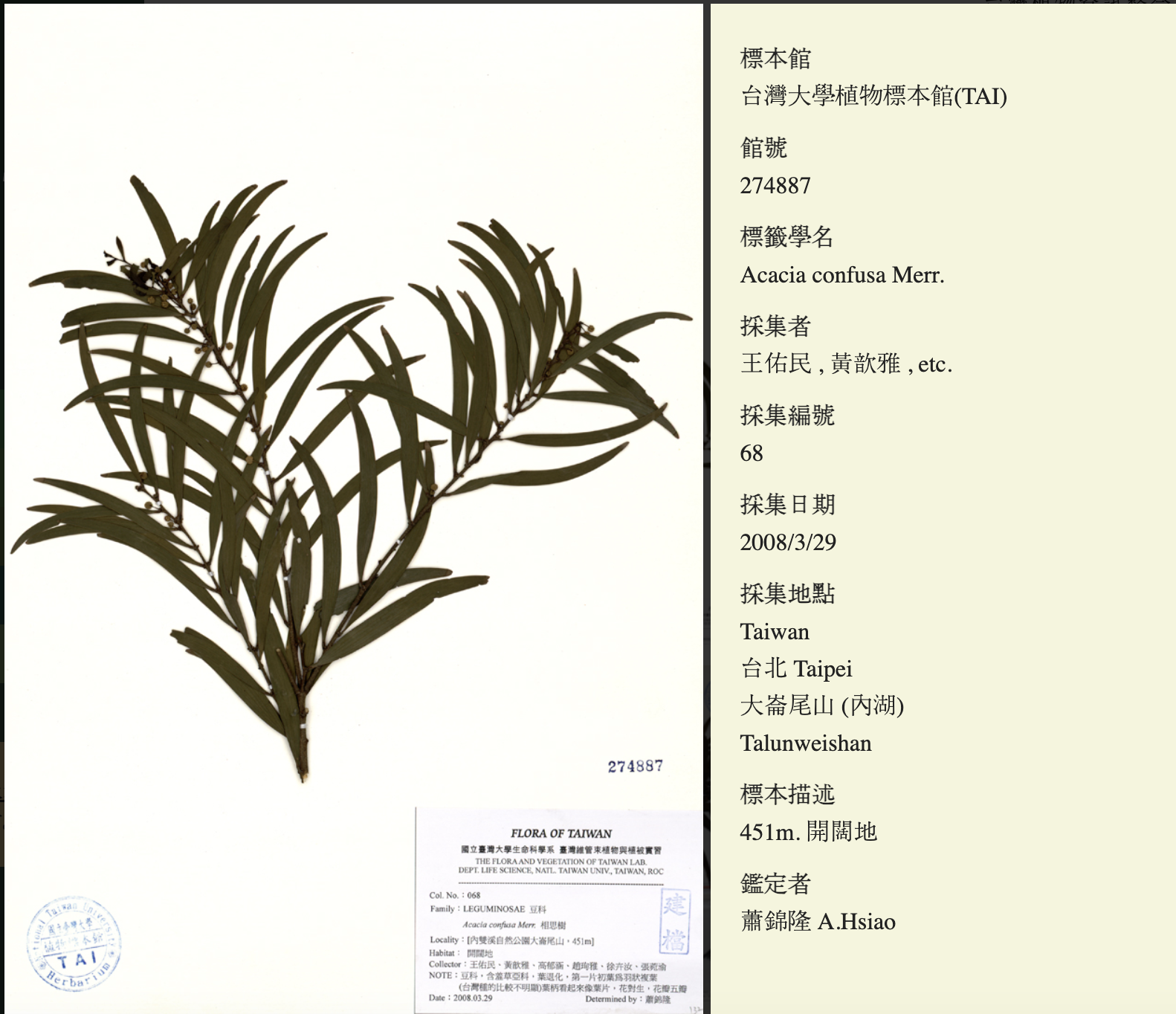

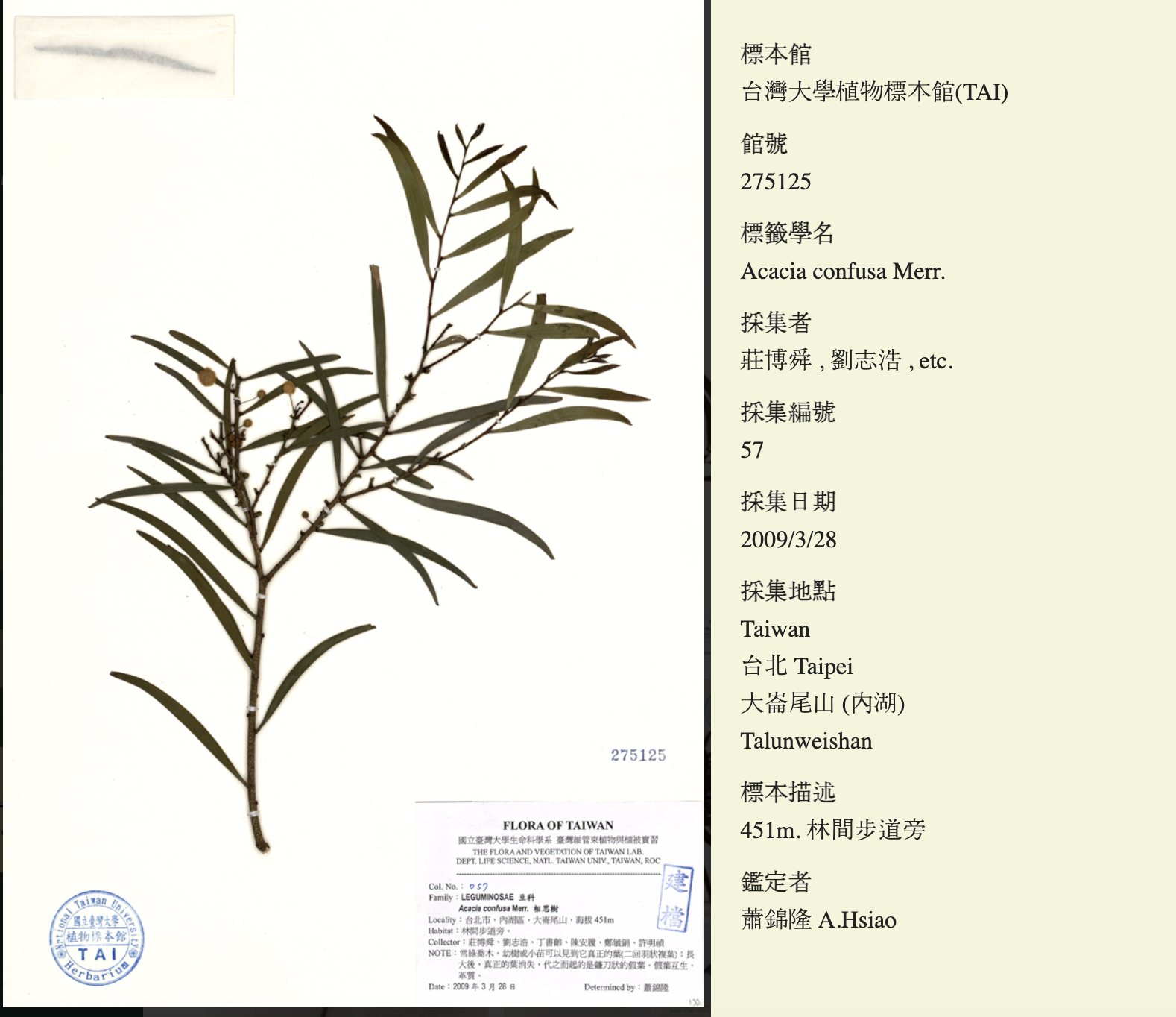

Photo Credit: National Taiwan University Collection Digitization Project

This is a fictional essay inspired by existing archives and personal encounters from the first half of 2024.

1.

IN THE SECOND half of the 2020s, I traveled repeatedly from New York to Taiwan, partly for study purposes, partly for other reasons which were never entirely clear to me, staying sometimes for just one or two weeks, sometimes for several months. On one of these Taiwanese excursions which, as it seemed to me, always took me further and further abroad, I came on a bustling early summer’s day to the city of Taipei. Even on my arrival, as the bullet train rolled in high speed across the city track into the dark station concourse, I had begun to feel unwell, and this sense of indisposition persisted for me the whole of my visit to Taiwan on that occasion. I still remember the uncertainty of my footsteps as I walked all around the inner city, down Huayin Street, Nanyang Street, Tianjin Street, Civic Boulevard, Dihua Street, and many other streets and alleyways, until at last, plagued by a headache and dazed by the kaleidoscope of street noise, dust, and food smell, I took refuge in the Fine Arts Museum, next to the Main Station, waiting for the pain to subside. I sat there on a bench in dappled shade, beside small, many branched trees called Acacia Confusa full of brightly blooming yellow flowers.

I could not help thinking of the taxonomy archive, Flora of Taiwan, neatly arranged on one of the library bookshelves at the National Taiwan University where I took a brief visit some years ago on the plea of attending a conference. It was a long text, unostentatiously typed on plain paper with dozens of pages filled with the contents of the table both written in Chinese and English. With beautiful illustrations and color photographs of the leaves, the depiction of the plant consisted of classification family, particular locations of growth, traits of its habitats, physical characteristics, and its local usages. Originally called xiāngsīshù (相思樹) by local communities, it symbolized “the tree of lovesickness,” under which people presumably waited for their loved ones to return. Over the past decade, this tree has attracted the attention of middle-class Western tourists for its spiritual and commercial potential due to the high concentrations of psychoactive tryptamines found in its root bark. The term “Acacia” is derived from the Greek word “akia,” referring to the sharp points of the thorns on a related species, and “confusa,” denoting confusion or uncertainty, but also symbolizing Confucianism, a Chinese belief system that migrated to Taiwan in the 17th century. The herbarium specimen, pressed and dried, documented and labeled with information about the place and date of collection and the collectors, stripped of its visceral connection to the local landscape and quickly given a new name seemed to facilitate its integration into the ethnobotanical database.

A soft breeze, possibly from Xiangshan Elephant Mountain, moved through the branches, making them sway slightly. The small, round, yellow flowers seemed to whisper softly in response.

2.

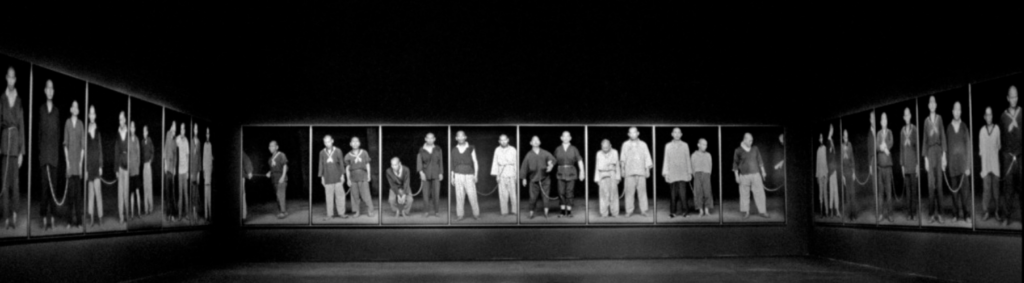

AS THE AFTERNOON drew to a close I walked through the museum, and finally went to see The Chain, which had first been opened only a few days earlier. It was some time before my bodily movements became accustomed to the structure of piled brackets in the form of suspended corridors that, together, formed a tubular-shaped composition.

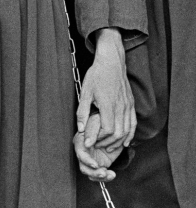

The monotonous walls of the inside space seemed to be repainted for the purpose of the exhibition, joined up with the steel-beamed glass windows. Upon smoothly passing through the myriads of tubular corridors, an overwhelmingly grand and dimly lit room took on the sight, filled with a horizontal chain of forty five black-and-white, life-sized portraits of inmates taken at a mental care institution called Lungfatang (龍發堂) in southern Taiwan. With a quotation from Dostoyevsky’s Diary of a Writer he almost certainly found the line in the preface of Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilization (1964) – “It is not by confining one’s neighbor that one is convinced of one’s own sanity” – the photographer Chien-Chi Chang (張乾琦) introduces his photo sequence in which 700 psychiatric patients live chained together in pairs, and are forced to tend more than one million chickens at the largest chicken farm in Taiwan.

I cannot now recall exactly what faces I saw on that visit to the surreal chain that bound around the wrists, but some faces have remained lingering in my memory. In the portraits of the pairs of mental patients in this real yet surreal drama, a stable patient was chained with one with more severe problems in an unorthodox kind of bonding therapy. I watched them closely for a long time, noting how their expressions revealed a hint of affectionate concern for their companions, attempting to project a sense of indifference upon being asked to look at the lens, with moments of spontaneous interaction and glimpses of impulsive emotions–uncomfortably reminiscent of humors, whims and childlike uncertainties–occasionally permeating the atmosphere. Otherwise, all I remember of the denizens of the Chain is that most of them had strikingly different hand gestures, and the ambiguous, secretive narratives the hands formed that don’t translate directly to sign language, found in certain paintings, ignite the imagination and curiosity of the audience.

I believe that my mind also dwelt on the question of whether Chang revisited the patients and their families when they were released from the temple after decades of living in “emotional chains.” Would they continue to live in pairs if they were to be immersed in the warmth of their partners’ presence? Would they not have dreams about hatching chicken eggs daily, surrounded by the feathers and sounds they produce? Wouldn’t they feel a sense of uneasiness sleeping in their own bed, having become accustomed to the temple’s dusty, bustling and crowded interiors? How would they have coped with their mental disorder episodes now, in the absence of the place where they have lived for decades?

Over the years, images of the vivid chains against the backdrop of the bleak interior of the exhibition room have become confused in my mind with my memories of the Taipei Mental Hospital, which was formerly known as Taiwan Imperial. If I try to conjure up a picture of the empty hallway of the inpatient ward today, I immediately see the chains of life-sized portraits, and if I think of The Chain, the massed ranks of bunk beds spring to my mind, probably because when I left the museum that afternoon, I went straight to the medical university campus in which the photo archives I found inside were so vivid that they led me to mix up where I had actually been, or rather first passed by the neighboring alley to look up the façade of that extravagant building, which I had taken in only vaguely when I arrived in the morning. Now, however, I saw how far the hospital constructed under the patronage of the Japanese Empire exceeded its purely utilitarian function, and I marveled at the white decorative elements creating a striped pattern, featuring a symmetrical design with a central section flanked by two slightly protruding wings.

When I entered the great hall of the medical university building beside the hospital, my first thought, perhaps triggered by my visit to the museum and the sight of the photo archives exhibited inside the dimly lit white cube, was that these several hundred inmates, after the suspension of the temple, must have been investigated by professional psychiatrists under the modernized medical diagnostic grammar, classified into different categories depending on the severity of their symptoms, and rehabilitated by teaching them simple labor tasks. It was probably because ideas like these struck me as another chain, a curious confusion which may of course have been the result of the sun’s sinking behind the city rooftops just as I entered the reading room. The bizarrely dry and serene atmosphere contrasted with the local climate, as well as with the gleam of gold and silver filtering through the rows of bookcases in the open access area when I crossed the threshold into the guarded space. Like the inmates who, as I assume, were relocated from Lung Fa Tang to the psychiatric wards, the readers inhabiting this space seemed somehow miniaturized, whether by the unusually insulated silence except for the subtle sounds of page flipping and the continuously operating air conditioning system, or because of the immensity of the historical records inscribed on and wrapped by papers.

3.

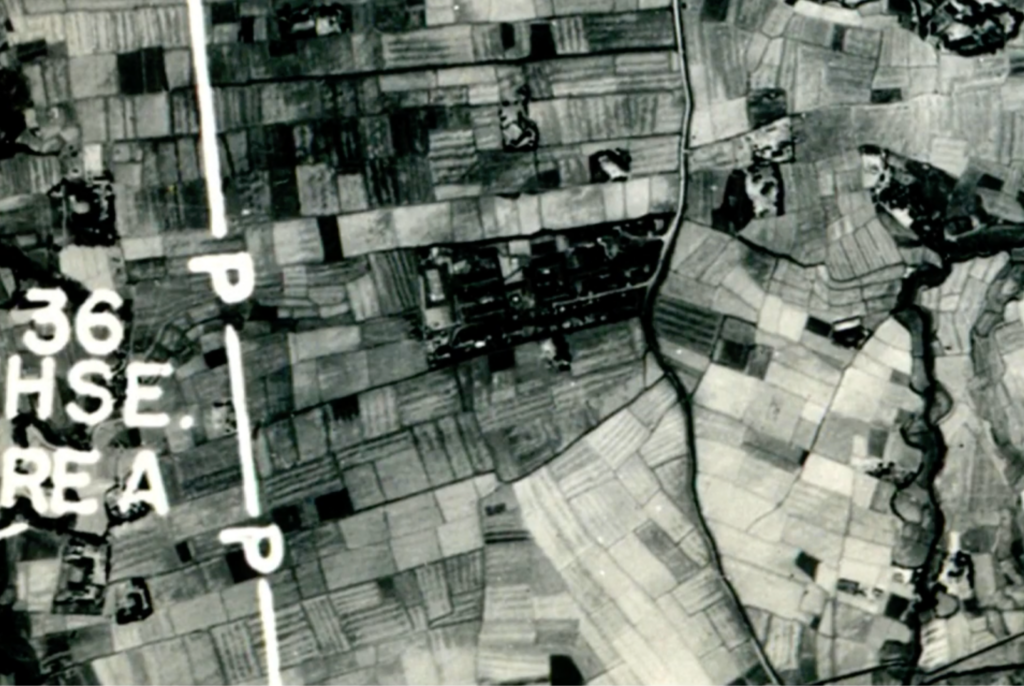

AS I WAS glancing through illustrations, images, and institutional records of the psychiatric hospital, I came upon an article – I don’t remember now if it was in the textbook for education and training for front-line staff members or the document of the Imperial University’s construction report–about the foundation of the first public mental hospital, Yǎng Shén Yuàn (養神院), as it is called in the official records, in 1934, four years after the Governor’s Office released an allocation of budget with a total amount of 300,000 yen to alleviate the (presumably) prevalent mental illness in Taiwan attributed to its maddening heat. While until the late 1910s the colonial government had stated that the care and custody of mentally ill patients was the responsibility of the patients’ family, relatives, and friends—a stance also reflected in the “Institutionalization of Mental Illnesses Act” in effect in Japan since 1900—the new “Mental Hospital Act” of 1919 explicitly mandated the government to establish widespread mental hospitals, which also provided legitimacy and momentum for the concept of building mental hospitals. According to detailed drawings of the building, one of the wards was built with iron grilles and locked at all times to treat dangerous patients, in which Shuzo Naka, the executive director then upon its establishment, examined and monitored them regularly.

Outside corridor besides the isolation room of the mental hospital. Image Source: National Taiwan University Collection Digitization Project

In the array of therapeutic endeavors of that period, ‘The Morita Therapy (森田療法)’ captured my attention. It was less a method than a philosophy, a beacon for those lost in the commotion of modernity, emphasizing a harmony between flexibility and autonomy, a necessity for those adrift in the industrialized work environment. Mitsuzo Shimoda, Naka’s primary mentor at Tokyo Imperial University, lauded the method as a significant Japanese invention in his book Psychology and Medicine (心理と医学), emphasizing it as an Eastern psychotherapy in contrast to Western approaches, noting its focus on the “inferiority complex” within neurotic personalities among certain Asian ethnic groups. Disciples of senior Japanese psychiatrists, tasked with supporting colonies such as Taiwan, Korea, and Manchuria, were able to implement and test therapy modules in various contexts and settings, facilitating the experimentation and adaptation of psychiatric practices across different colonial landscapes. Analyzing notes and diaries of his patients, Naka, as well, incorporates the method during his tenure at Yǎng Shén Yuàn. In the Governor’s Office Annual Report, Naka gives a detailed account of his patients’ symptoms, his treatments, and their effects, where continuing work even in the absence of motivation is encouraged, fostering a natural emergence of a desire to work. This process, he notes, leads individuals to realize that the symptoms which previously tormented them are, in essence, psychological.

I also spent several hours reviewing medical records from 1939 to 1942, the period when Naka became a professor at Taipei Imperial University, and there, among case reports of a Taiwanese youth undergoing the therapy, I came upon the report on a 25-year-old case–hereinafter referred to as Mr. A–who was a student at a high school in Taipei. This was also the year the Department of Psychiatry was founded, coinciding with the establishment of a 20-bed psychiatric ward in the affiliated hospital, which later evolved into the Taipei Mental Hospital. Coming from a wealthy background with a large family garden but has been out of school due to his suffering from neurasthenia – based on the diagnostic classification used by Naka – Mr. A was grappling with a mix of psychological and physical symptoms. Following the instructions of Morita Therapy, Naka encourages him to focus only on the work tasks. Despite his frustration with the tension between local Taiwanese and Japanese officials during his high school days and facing cultural dilemmas like the Taiwanese tradition of arranged marriage, Naka only offered general advice to focus on becoming a promising individual for the broader good, rather than dwelling on the societal realities around him. Amidst one of the sessions in which he reveals his concerns about Taiwanese identity and the social discrimination, Mr. A asks Naka: “Is this the reality of society? Or am I too neurotic?” Naka replies: “Don’t be restricted. You should be your own master wherever you go. For the sake of the Oriental nation, to become a promising young man. A sparrow knows the ambition of a swan.” After several months of therapy sessions which included a series of ‘electrical shock therapy’ and ‘water bath’, Mr. A, upon his hospital discharge, reevaluates his aspirations, deciding against further education to instead embrace practical knowledge and work as a civil engineering contractor, utilizing his skills for local and national benefit. He reconciles his view on love, prioritizing personal fulfillment and contribution over blind passion, and resolves to balance his future ambitions with his emotional life, indicating a matured perspective on life and duty.

4.

WHEN I TOOK leave from the reading room, making my way down the staircase to encounter the air heavy with moisture, the dimming light of dusk filled the landscape in shades of gray and lavender. It was then that I noticed a man nearby, remote control in hand, his gaze lifted to the vast expanse where the last rays of sun fought against the creeping shadows. The air, thick with the day’s last breath, carried the sound of cicadas, mingled with a distant mechanical hum. This hum grew clearer as a drone, like a creature of dusk, made its descent towards the man, reclaiming its physical form from the twilight. With focused attention, he observed the drone, which had been capturing the city’s transition from day to night, its satellite view revealing the melancholy of urban twilight. “The city carries a bit of a sense of sadness, does it not?” he mused, suggesting the moisture in the air might amplify this sentiment. My rudimentary understanding of the local language confined me to silence; I could only nod in agreement, sharing a moment of quiet reflection on the ephemeral moment of dusk.

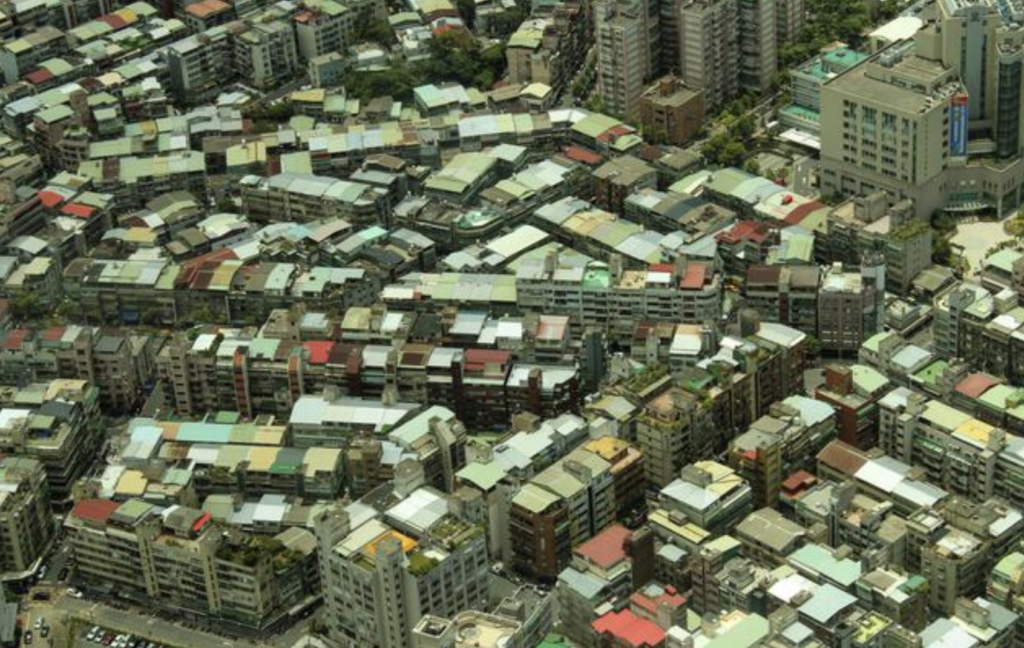

No. 372 Wufengpu, Songshan Village, Qixing County, Taipei Prefecture

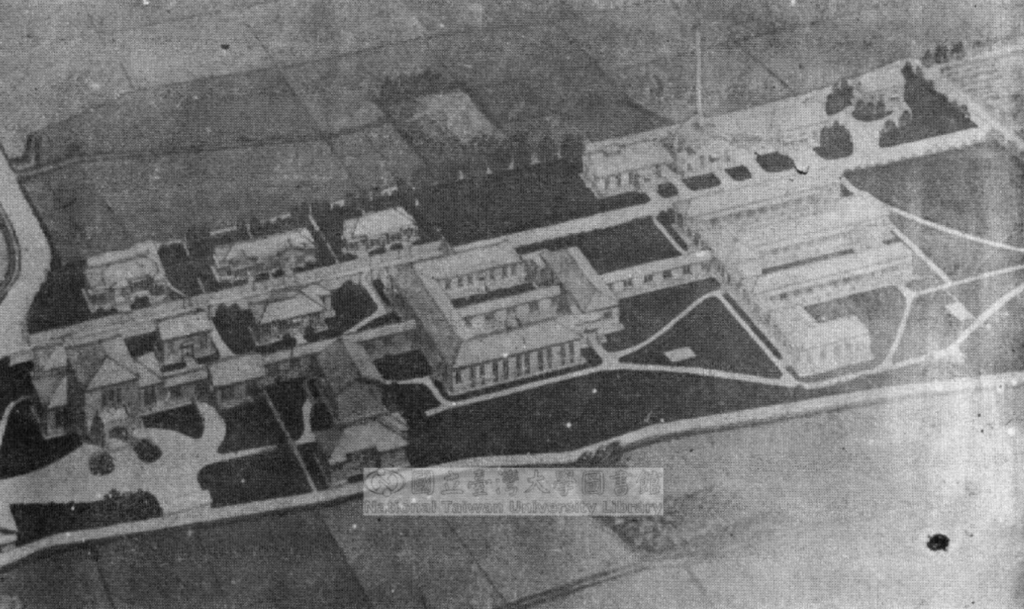

While I was inside the reading room, I had jotted down the location of Yǎng Shén Yuàn, which had stood for several decades until 1968, with its architecture highly resembling that of the Amsterdam Dolhuis or madhouse renovated in 1617, on my palm to visit it on my way back to where I was going to spend my first night. According to the current address, it is No. 138, Hulin Street, Taipei City, so I typed it into the virtual map to get directions. Although I was mostly inside the metro train while traveling, my shirt was drenched with sweat. It was unusually hot for the time of year, and large nimbus clouds were piling up on the southwest horizon as I crossed the eight-lane road. After hours of looking at photo and document archives, I still had an image in my head of an expansive compound with multiple buildings, chimneys, and pillars towering above a precise geometrical ground plan. However, what I now saw before me was a complex of multi-storied residential buildings showing signs of age and wear with green awnings, exposed utilities, and air conditioning units, as if the sanatorium had never existed. It was only by following the archaic traces of the ‘psychiatric theater’ that I could grope through the blend of sights, sounds, and smell. Pedestrians were walking along the bustling alley, merchants with their sleeves rolled up leaning against the building walls ready to close their stores, and motorcycles weaving through the narrow lanes. I felt reluctant to pass through its narrow passage into the ghostly remains of the psychiatric wards, but as I began walking on the very lane which had presumably been the center aisle of the building, the people on their wanderings and passing in tides suddenly seemed like mysterious processions moving towards the dark, as night was gradually falling over the dusk.

Aerial photograph of Yǎng Shén Yuàn, 1934. Image Source: National Taiwan University Collection Digitization Project

Aerial photography of the current scene at the same location, 2024

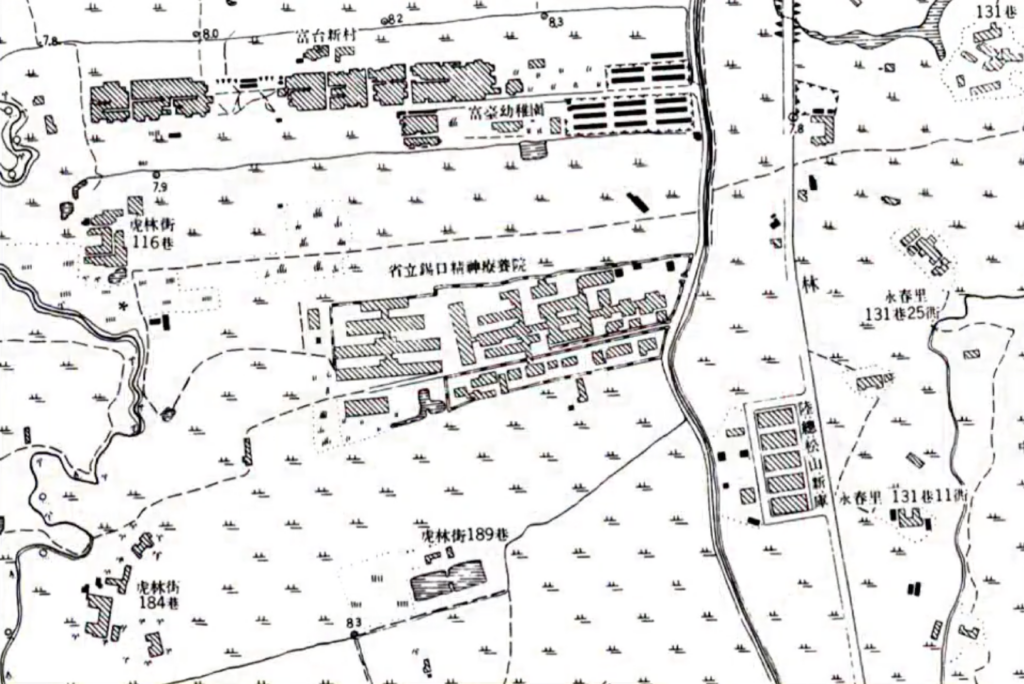

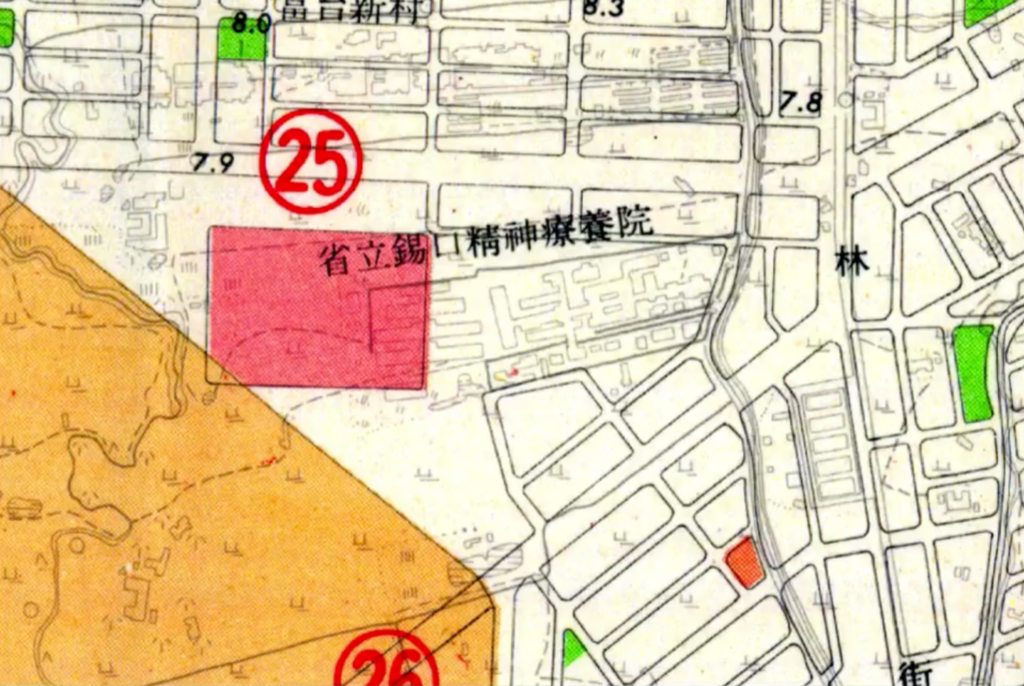

Historiographic sequences of Yǎng Shén Yuàn. Years taken (from top): 1936, 1944, 1956, 1968. Image Source: National Taiwan University Collection Digitization Project

References

張子午, 2018, 龍發堂最後的日子, The Reporter, https://www.twreporter.org/a/long-fa-tang-mental-disoder (last visited: 2024-03-15)

陳信諭醫師, 2018, 龍發堂的緣起、傳奇與爭議:臺灣精神醫療史上一頁難以分類的篇章, https://storystudio.tw/article/gushi/longfatang-kaohsiung (last visited: 2024-03-15)

巫毓荃、鄧惠文,〈熱、神經衰弱與在台日人:日治晚期台灣的精神醫學論述〉,《台灣社會研究季刊》54 (2004):61-104。同文經增補資料修訂後,以〈氣候、體質與鄉愁──殖民晚期在台日人的熱帶神經衰弱〉為題,收入於李尚仁編輯,《帝國與現代醫學》(臺北:聯經出版公司,2008),頁55-100。

Chang, Chien-Chi. (1998) The Chain – selected photo archives taken inside Lung-Fa Tang Temple, https://www.magnumphotos.com/newsroom/society/chien-chi-chang-the-chain/ (last visited: 2024-03-19)

Boufford, David E. Hsie, Chang-fu. (2003) Flora of Taiwan Vol 1. National Taiwan University, Department of Botany

Kitanishi, Kenji & Mori, Atsuyoshi (2008) Morita therapy: 1919 to 2015. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 49(5). pp. 245-254. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1995.tb01896.x

Trouillot, M. (1995). Silencing the past: Power and the production of history. Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press.

Wang, Sumei. (2017) Radio and Urban Rhythms in 1930s Colonial Taiwan. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 38(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2017.1285152

Wu, Harry Yi-Jui & Cheng, Andrew Tai-Ann. (2017) A History of Mental Healthcare in Taiwan. In: Minas, H., Lewis, M. (eds) Mental Health in Asia and the Pacific. International and Cultural Psychology. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-7999-5_7

Notes I randomly took for thought processing (‘Is this an archive?’)

… The act of archiving has increasingly been conceptualized or even equated with the mechanisms of colonial power. Azoulay (2017) defines an archive as “a place or a threshold, a repository of documents or an apparatus of rule, an achievement or a contested act of violence.” For they are predominantly collected by centralized governing bodies, accumulating documents in layers and safeguarding them for specific purposes. Individual stories and events are subjected to the grand narrative of the colonial institutions, classified and categorized into the historiography and the making of the nation-state. During the so-called golden era of the information age, where individuals were not merely invited but compelled to grant institutions access to their personal information for using their technology and maintaining a ‘working life,’ the most private everyday lives were silently collected, organized, and analyzed.

Yet, no one is able to challenge the imbalance of power regarding archives, as the extraction of personal data by technology companies was a legitimate action, agreed upon through contracts that consented to the deep probing of one’s private life in exchange for material possessions. Individuals must struggle for their lives in order to adapt themselves to the biopolitics of “faire vivre.”

It became unimaginable to conduct research without ‘possessing’ a personal laptop, a smart phone, and enough space in the google drive. Although jotting down various notes in a handheld notebook sparks thought, producing a finished ‘work’ necessitates creating content through electronic devices. The cost of engaging in a certain act requires certain assets. However, was the notion of “the right” without a cost ever possible? This notion somehow evokes a sense of being punished. Why doesn’t the slogan “of the people, for the people, by the people,” resonate deeply with her? What does “access” mean in this context? What does it mean to acquire information? Busy hands, a mouth ready to speak, a mind’s endlessly turning gears, compelling and organized writing, bodies poised to sprint—all of these she observed. Yet, she feels no sensation in her feet. It’s cold, raining, and there’s nowhere to shelter. Everything has a cost. How much capital remains for her to cover these costs? Where can she obtain more capital? Contemplating this eventually leads to a numbness in some part of her body, so profound that she forgets the coldness.

Landscape – forgotten – abandoned building – ghost strata – why are we so obsessed with ghosts?

Beginning with addressing my uneasiness in embodying the possessive nature of ‘human rights,’ I wanted to pose a question on agency, originally regarded as the basis of autonomous thinking.

Kant characterized the Enlightenment as an expansion of knowledge made possible by man’s courage to refuse the tutelage of others and use reason freely.

The view of history as the narrative of progress toward an improved state would become increasingly dominant in the nineteenth century. The function of archive as a means for an increase in knowledge was to be cumulative, progressing toward the final realization of freedom in its universal form.

Instead of presupposing the fixed norms of existence, I’d like to focus on the process of thinking along the lines of modernity – the threshold and the minimum criteria of maintaining a social life. As Derrida observes, memory serves as a psychic archive where real experiences are both preserved and obliterated upon inscription, which consists both of the technological milieu of the material and the affective and abstract semantics.

Thus, my purpose of the essay is to look into the grammar and forms of archive in our contemporary daily lives — including index, recording devices, and the availability of curatorial choices — that enable us to engage in various social systems.

I’ve been having trouble finding a specific case to look at its trajectories and traits that function as a framework of understanding contemporary forms of life. I end up situated in the field of media studies (a.k.a Friedrich Kittler’s works where he looks into the intricate relationships between technology, media, and military.) Take, for instance, the emergence of machine learning and how it impacts on the process of our decision making.

But what about psychic archives? The archives in which we preserve our most intimate memories largely pertain to aesthetics. Aesthetics is a certain appreciation of beauty which can range from the standard of sensorial order, cultural patterns which lead to the judgment of tastes. The psychic archives contain the potential of collective projects on political changes – e.g. the politics of nostalgia.

The exergue, the grammar, the hermeneutic apparatus through which documents are generated.

The liminal spaces, the borders, and the internal frontiers (Stoler, 2022)

Piason Natali argues that nostalgia is a distinctly modern word, an idea dependent on a way of worlding that is distinctive to modernity. That is, having and not having arise together (2)

The word nostalgia’s life was over as a medical condition (Johannes Hofer), as the conglomeration of symptoms previously associated with nostalgia was absorbed by other diagnostic categories and came to be connected with melancholia and, later, depression.

For Marx, nostalgia – the yearning for the past – was an explicitly political problem—an obstruction to social justice. Often the suspicion came from the assumed connection between nostalgia and the preservation of privilege. Those devoted to the past inhibit history’s progressive movement towards less exploitative modes of production. Marx makes the call for the burial of the dead to be left to the dead themselves, appealing to such notions as false consciousness and alienation.

The Dead Don’t Die (2019) – Within bourgeois society itself, these elements from earlier social formations will be found as “unconquered remnants” of the past. Those who inhabit such spaces are walking dead; they are “alive as if they were dead.” They are akin to those Dipesh Chakrabarty called the “living dead in our midst”

Nostalgic practices have been insistent throughout the social lives of humanity both within and across national borders. The power of nostalgia is precisely its susceptibility to being co-opted into various political agendas, which nostalgia cloaks with an aura of inevitability. Walley – viewing these very same nostalgic practices as critical and subversive. The political kitsch – reading nostalgia into politics.

A better understanding of how individuals and groups remember, commemorate and revitalize their pasts, and the crucial role played by nostalgia in the process of remembering. – ‘a new phase of accelerated, nostalgia-producing globalization’ (Robertson 1992: 158). – ‘accelerism’ (the acceleration of modern temporality coined by Robert Musil in The Man Without Qualities) The nineteenth century saw nostalgia lose its clinical connotations and started to take the metaphorical meaning of longing for a lost place and, especially, a vanished time. A crucial role in the formation of anthropology as well, with the first ethnographies by Franz Boas, Bronislaw Malinowski, Edward Evans-Pritchard and Marcel Griaule, among many others, fuelled with a longing for vanishing societies and ruptured equilibriums – a structuring temporal framework for the social sciences, when many anthropologists were blind to their own usage of time (Fabian 1983). – In the wake of the literary turn, researchers paid more attention to the past as it is lived by social agents and to concepts closer to human experience (Ricoeur 2000)

A more phenomenological approach, capturing the way people remember, forget and reinterpret their own past.

The social aspects of nostalgia – Recent anthropological literature has confirmed that nostalgia as affect, discourse and practice mediate collective identities, whether they are social, ethnic or national (Bissell 2005, Bryant 2008, Cashman 2006, Herzfeld 2004). Nostalgia is ‘a potent form of such subaltern memory’, underlining ‘nostalgia’s empowering agency’ and ‘critical potential’ (2010: 181)

Svetlana Boym distinguishes between nostalgias that are ‘restorative’, aiming at the ‘transhistorical reconstruction of lost home’ (Boym 2001: xviii), and those that are ‘reflective’, ironic and longing for the longing itself.

This raises important questions for anthropologists: what forms can nostalgia take and, when identified, how to grasp them in thick description? – the very complexity and ambiguity of memory practices that we should strive to describe

In the fabric of nostalgia, physical objects play an important role. Not unlike the famous madeleine cake of Proust, materialities mediate people’s relationship to their past and, often, they trigger powerful mnemonic responses (Parkin 1999, Radley 1990).nostalgia for communism remains a contentious semantic space.Bach examines the symbolic and economic appreciation of everyday life objects that came to epitomize the socialist era, emphasizing how they have been transfigured into what he terms ‘nostalgia-objects’

massive purchase of socialist objects by local collectors, today obsolete as compared with newly imported Western goods, constitutes a mourning for some aspects of their past. Bach’s study of the re-evaluation and re-appropriation of GDR objects further teases out the complex process by which nostalgia intervenes as a vector of cultural transmission.

nostalgia is ‘a force that does something’ (Dames 2010: 272).

Milan Kundera in The Unbearable Lightness of Being when he writes: ‘In the sunset of dissolution, everything is illuminated by the aura of nostalgia, even the guillotine’ (1984: 4).

its pragmatic conditions and effects.

Perhaps such days have always been a dream rather than a reality, a phantasmagoria of loss generated by modernity itself rather than its prehistory. But the dream does have staying power.

Nostalgia moved beyond depictions on screen, seeping into the stuff of everyday life, linking desire to design, décor, and dress.

Nostalgia – Therapy – linked to ideas of displacement and loss.

The emergence of “memory sciences” at the end of the 19th century, which includes psychoanalysis, draws from phenomenological psychiatry and philosophy, notably the works of Eugène Minkowski and Martin Heidegger.

After several decades of declining influence, psychoanalysis is now enjoying a revival of public interest and intellectual esteem. The notion that the stories we tell ourselves, especially about our own past, are false or incomplete. Those stories make up both the foundation of our identity—the “I” of Western society consists of such experiences and affinities—and potentially the bars to our cages, because they trap us in patterns of thought and feeling that may lead us to destruction. The patient comes to treatment because he is suffering, yes—but more fundamentally, because he has reached a narrative cul de sac.

The neuropsychoanalysis movement “attempts to infuse into neuroscience some of the real, lived complexity of the life of the mind, and conversely, to introduce into psychoanalysis some of the scientific rigor of neuroscience,” The late British neurologist Oliver Sacks wrote that the joining of neurology and psychoanalysis would be “a profound and almost unimaginable union . . . between the inner and outer approaches.”

“I think we may be starting to make progress.” But the extended reminiscence that Solomon published after Friedman’s death, “Obituary for the Analyst,” also reminds us of how complex, mysterious, and even beautiful the therapeutic process can be.

The result is a retrofitted psychoanalysis that is humbler, hipper, more communicative, and considerably more tolerant than it has been since Freud first floated his revolutionary notions in Vienna. The rigid neo-Freudian orthodoxy that long held a lock on American psychoanalysis has gradually given way to a gentler theoretical pluralism, and, in a major sea change, analysts are no longer required to have medical degrees.

revival of psychoanalysis – autonomy – documentation – make live

Biochemistry of memory and its social locations and functions

Neural maps implied in most visions of biological memory and the social maps

A graphic trace – the spirit of ‘pastness’ itself –

What about myself? I have recently begun talking therapies, and I also take psychoactive substances here and there to fully be and focus at the moment and the environmental surroundings.

Psychedelic-assisted-therapy is an interesting realm to touch upon, for it often leads to a rearrangement of navigating forms of life via neurological input, noetic experiences, and dream tripping – the urge to play with consciousness. Human design has become a popular framework for assessing personalities as a way to understand ourselves in the most sophisticated sense.

But most importantly, my own personal concern always had to do with money. How money flows and enacts certain narrative is such an interesting question to inquire about.

Maybe I can delve into the revival of psychoanalysis in the field of psychiatry?

How does psychoanalysis function NOW versus THEN?

What are the roles of dreams and secrets – or the so called ‘unconscious’ – when it comes to our memories?

Unconscious as the medium of determination by the past, but as an inexhaustible source of novelty in life? From inductive reasoning to paradigmatic perception shift.

How can this field of psychoanalysis be discussed in the political economy?

As a talking cure, psychoanalysis should depend on the discourse of the patient – how did the sciences of memory (including psychoanalysis) and phenomenological psychiatry and philosophy change and evolve? With Kittler’s historiographical approach – the relationship between literature, madness and truth.This era is exposed to the history of struggles to occupy places, a history filled with violence. Archives are remnants of a battleground. She surfs through the (…) In 1929, Freud – psychoarcheology – sovereignty –

Personal and intimate aspects of documents – the potential for collectivity

Sadness and melancholia.

Archive represents the form of memory—a mechanism for perception which encodes and institutionalises(res-) publica into impenetrable secrets.

The material aspect of the archive, or “the technical model of the machine,”

Both the inscription on the external medium and the intimate marking that obscures the boundary between external and internal

Collective memory through narratives of nostalgia

‘Ethnography of archiving’ – to detail the judicial and non-judicial discourses and bureaucratic maneuvering involved in the creation of an archival report, thereby unraveling the power relations, mediating processes, manipulations and bureaucratic performances that make commission reports problematic even today

In its dominant version, it contends that the historical narrative bypasses the issue of truth by virtue of its form. Narratives are necessarily emplotted in a way that life is not. Thus they necessarily distort life whether or not the evidence upon which they are based could be proved correct’ (6)

Making the (interactive) archive the basis of collective memory, rather than leaving memory as the substrate which guarantees the ethical value of the archive – Allowing new traffic across the gap between the internalities and externalities of collective memory

The work of the imagination – proliferation of imagined worlds and imagined selves

People can ‘craft’ the scripts of possible worlds and imagined selves –

Re-writing time and agency – the deconstruction of the Western concept of invention – time articulates people’s understanding of agency: literally, what makes things happen and what makes acts relevant in relation to social experience, however conceived (Greenhouse, ) – not necessarily be restricted to humanity – This account of agency is shaped by the socially produced articulations of time that underlie it

When a culture is guided by a different temporal schema, agency can be understood quite differently. –

‘The constructivist one denies the autonomy of the sociohistorical process’ – ‘the historical process has some autonomy vis-a-vis the narrative’ (13) – ‘Few of us engage in an explicit recall of images every time we routinely tie our shoes’ (14) – Memory systems are inextricably linked in practice – ‘There is evidence that the contents of our cabinet are neither fixed nor accessible at will’ (14) – Events otherwise significant to the life trajectory were not known to the individual at the time of occurrence and cannot be told as remembered experiences’ (15) – The revelation itself may affect the narrator’s future memory of events that happened before (15) – ‘That past is constantly evoked as the starting point of an ongoing traumatism and as a necessary explanation to current inequalities suffered’ (17)

Limit the range and significance of any historical narrative.

A castle, a fort, a battlefield, a church, all these things bigger than us that we infuse with the reality of past lives – Embody the ambiguities of history – The mystery of their battered walls (30) – We suspect that their concreteness hides secrets so deep that no revelation may fully dissipate their silences. We imagine the lives under the mortar, but how do we recognize the end of a bottomless silence? (30)

If the museum is dominated by historical time, it also means that history has screened out many events and been ignored. The spatial entity of “discovery” created by classification and screening, or the emergence of “found objects” as art objects in art history, is originally the complementarity and vacancy created by the loss of historical time. The relationship between space and objects has been activated through different historical times. It is certainly curious whether there is an Asian version of Surrealism. In East Asia, in which art is regarded as a foreign product in the face of “modernity” and art becomes a language that needs to be learned, the relationship between art and Western viewing on the small island of Formosa may need to be considered more carefully. The trend of Surrealism started in 1930 almost at the same time as Freud’s theory entered East Asia.

Exploring the strange modernity produced by the translation and transplantation process of psychological science at that time.

… W.G. Sebald

[1] In January 1969, the United States and Taiwan governments signed an official agreement of academic collaboration to publish the first edition of Flora of Taiwan. Completed and published between 1975 and 1979, which includes six volumes, there are 562 pages in Volume One, 722 pages in Volume Two, 1,000 pages in Volume Three, 994 pages in Volume Four, 1,166 pages in Volume Five, 665 pages in Volume Six, and more than 5,000 pages in total. The contents include the accepted names and synonyms, descriptions of all taxa, indented dichotomous keys to different taxa, citation of herbarium collections, geographical ranges and habitats, bibliographical references, illustrations and color photographs, directory, and index, covering 233 families, 1,355 genera and 4,220 species of indigenous vascular plants in Taiwan.

[2] Founded in 1971 by an abbot named Li Kun-Tai in Kaohsiung, Lungfatang was originally a Buddhist temple. Li’s approach to healing involved a unique method where he tied himself with a straw rope to his friend’s son, a young man suffering from mental illness who sought to become his disciple but was unable to attend to his basic needs. Through this method, Li explained principles and taught him how to behave. Remarkably, within a few days, the disciple became cooperative and appeared to undergo a transformation. As word of mouth spread about this unconventional method of healing, the small Buddhist temple, Lungfatang, began to continuously receive patients brought by their families for care.

Twenty years after its inception, Li had since renamed himself Hieh Kai Feng, and had accumulated 600 mentally ill assistants. Most were bound together with chains, having been entrusted to his care by their families, who were overwhelmed by the stigma of caring for individuals considered lunatics or societal outcasts. What was expedient in the early years later evolved into the famous “emotional chain,” which connected the restless and passive people with iron chains.

A decade on, by 1999, the temple had become Taiwan’s largest chicken farm, boasting a population of a million chickens that laid eggs and produced waste in nearly identical volumes. The farm was maintained by 700 mental health patients under the temple’s supervision, navigating through a mix of slurry, eggs, and chicken carcasses. To improve upon the limitations of using string for control, Hieh Kai Feng had transitioned to using light chains as a more effective method to manage the significant number of patients. He connected them one by one, throughout the day and night. Satisfied with the outcomes, he took pride in his system, convinced that his efforts were not only in the best interest of his patients but also significantly relieved the families of the heavy responsibility they bore. Later on, he trained the public in talents such as song-jiang dancing and wind instruments, demonstrating miraculous treatment results.

The temple/rehabilitation institution was suspended at the end of 2017, after a severe cluster of amoebic dysentery and tuberculosis broke out in the temple. After sending thirty one infected patients to the hospital for treatment, the Health Bureau of Kaohsiung City relocated the patients to professional medical institutions depending on the severity of the symptoms. From the end of October to the beginning of November, a number of psychiatrists were stationed to diagnose all patients, including the master of the temple.

In 2018, Wen Rongguang, the first psychiatrist to enter the investigation of the temple in the 1980s, went to the inmates and conducted in-depth interviews with video recording equipment. (**)

The story of the two cases illuminates the complex nature of the incommensurable differences in the epistemologies of mental health care. On one hand, Lung Fa Tang took pride in its unique achievements in patient care, opening its doors to professionals to showcase its work and seek recognition; on the other hand, there were mission-driven pioneers of mental health care, eager to explore autonomous, non-medical models.

[3] Morita Therapy is an inpatient psychotherapy method developed by the Japanese psychiatrist Shoma Morita in the late 1910s, designed primarily for patients with neurotic personality disorders. Morita posited that the neurasthenia prevalent in Japan at the time was not a neurological or physical illness, but rather stemmed from the psychological impact of neurotic tendencies. He argued that neurotic individuals’ fear of death reflected their intense desire to survive. The core of Morita Therapy involves guiding patients to engage in spontaneous work, thereby experiencing their profound survival instinct. It aims to foster an attitude towards life that integrates with the real world, encouraging the pursuit of self-realization within it.

[4] Shim-pua marriage was a Taiwanese tradition of arranged marriage, where a poor family (burdened by too many children) would sell a daughter to a richer family for labour, and in exchange, the poorer family would be married into the richer family, through the daughter. The girl acted both as an adopted daughter (to be married with a young male member of the adopted family in the future) and free labour. Due to the lower-class status of the girls, discrimination was often present, and slavery-like treatment was not uncommon. Marriages occurred after puberty, with ceremonies ranging from lavish to simple, based on financial means. The practice, common in poor and rural areas, ensured sons had wives and helped continue family lineages, contrasting with costly “major marriages.” Shim-pua marriages declined with societal and legal changes by the 1970s.