by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

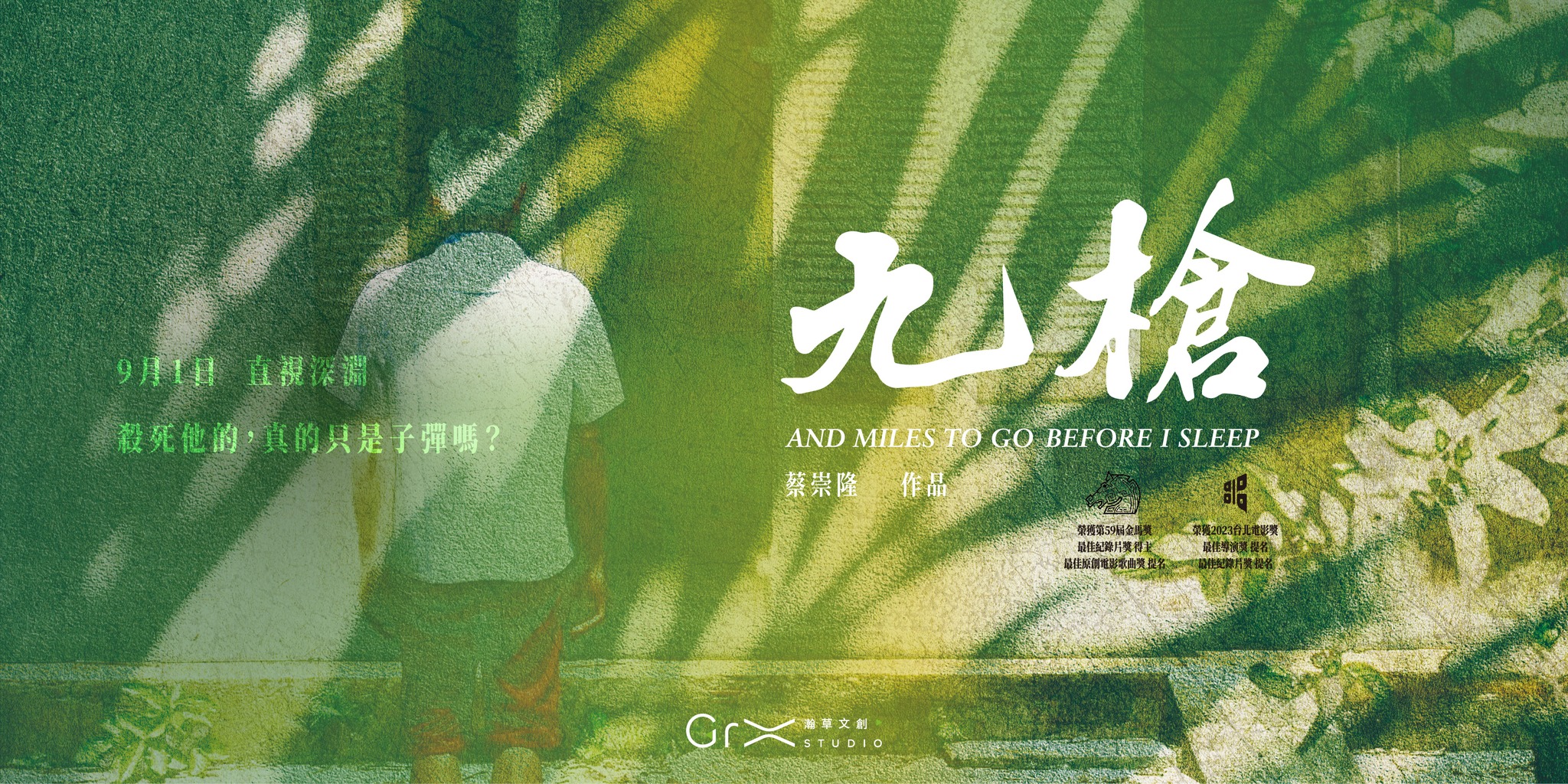

Photo credit: Film Poster

AND MILES TO GO BEFORE I SLEEP proves a powerful document of the contemporary situation facing Taiwan’s migrant workers.

In particular, the documentary focuses on the series of events around the shooting death of 27-year-old undocumented migrant worker Nguyen Quoc Phi in August 2017. What provoked widespread outrage from migrant worker advocates at the time was that Nguyen was shot several times by police and left to bleed out, with no effort to perform CPR. This is where the title of the documentary in Chinese, “Nine Shots” (九槍) comes from.

Police claimed that the use of force was justified, seeing as Nguyen attacked them with rocks and was attempting to steal a patrol car. However, questions were raised about this story by Nguyen’s family and acquaintances, seeing as he did not know how to drive.

A significant portion of the documentary hones in on Nguyen’s death. The police camera footage of the shooting is replayed many times in the course of the film, showing that police were more concerned with sending a police officer with a nosebleed to the hospital in the first ambulance that arrived at the scene after the shooting than treating Nguyen.

Police officers interviewed in the film suggest that the officers on site did not realize that they had fatally injured a man, not having had the training to have learned this. Police continue to treat Nguyen as dangerous in spite of his fatal injuries, dragging him out from under the patrol car insisting that he would not feel pain, and cuffing him even when he is in no condition to resist. As Nguyen’s defense lawyer comments, by that point, Nguyen was only “a piece of meat”—already dead, but simply flailing about, even as officers still treat him as some hazardous, deadly danger.

The documentary is highly effective in combining the use of documentary and news footage with footage shot in a more cinematic lens. Nguyen’s death is initially presented through a mixture of cinematic footage shot in the location where he died interspersed with police footage of his death.

To some extent, the movie uses a mythopoetic frame to allow viewers to understand Nguyen as a person after his death. Male narration in Vietnamese reads from Nguyen’s personal reflections, as drawn from Facebook posts, not dissimilar to the style of documentary that has become popular in Taiwan in recent years through movies such as Le Moulin, mixing documentary and art film. This is used alongside interviews with Nguyen’s acquaintances, such as his parents, siblings, and a Taiwanese friend.

Yet the documentary ultimately uses Nguyen’s death as an entry point in the larger constellation of issues facing migrant workers in Taiwan. The movie goes on from Nguyen’s case to discuss the conditions facing migrant workers in factories that they would want to flee the conditions of their workplace, or with regards to how the freedom of movement for migrant workers was restricted during COVID-19.

To this extent, the film goes on to elucidate how migrant workers take on the dirty, dangerous, and demeaning tasks that Taiwanese do not want to do themselves so that Taiwanese can live relatively luxurious lives, and yet there is significant fear-mongering around migrant workers. Industrial accidents, the beatings and even the killing of migrant fishermen on the high seas, and the deaths of migrant workers in factory fires are highlighted.

This uses, similarly, footage of migrant workers themselves as they work, as well as interviews from experts. A particularly powerful interview is with a Taiwanese firefighter who describes being haunted by the feeling that if he had acted faster, there would have been more of a body to recover from a factory fire–from his comments describing the intensity of the flames in the tin-plate buildings that factories are frequently built from, one realizes that as a firefighter with not only first-hand experience but a significant degree of technical expertise, his view is that survival in such structures after a fire breaks out is virtually impossible.

Though And Miles to Go Before I Sleep clearly takes the side of migrant workers, other viewpoints are also represented. In one part of the film, the documentary juxtaposes interviews from employer organizations, migrant worker brokers, and migrant worker advocates. Even as employers frame migrant worker brokers as at fault and brokers frame employers as at fault, what emerges from all three groups is a view that the import of migrant work as labor is deeply tied up with the government, going back to Taiwan’s authoritarian period.

Similarly, the movie interviews the sister of the officer who shot Nguyen to show her perspective. However, some of her comments prove rather shocking, such as suggesting that the Philippines should be a positive example for Taiwan in that police officers who take violent actions against drug users there do not face such harsh punishment.

As such, an underdeveloped aspect of the movie is how police officers and others justify actions against individuals using drugs–such as Nguyen may have been at the time of his death–as not having fundamental human rights. The movie argues that some may turn to drugs because of the pain from their work or other reasons, but the dehumanization of drug users in Taiwan could have seen more discussion.

Either way, And Miles to Go Before I Sleep is a powerful work. Though graphic and, in fact, quite shocking, the documentary is not to be missed, for shedding light on important social issues facing contemporary Taiwan.