by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Online Screenshot

CHINA HAS been rocked by protests in the past days, which have taken place in major cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu, and others. The protests, which are broadly against the restrictive measures maintained in China as part of COVID-zero, broke out in the wake of a fire in Urumqi that killed ten and injured nine.

Some believe that the actual death toll may be higher. Namely, outrage ensued because firefighters were unable to enter the complex to rescue victims because of measures against COVID-19, locking victims inside as they burned. This takes place in the wake of riots in Zhengzhou at FoxConn facilities against new regulations that would have required workers to work through the Lunar New Year holiday, mere weeks after workers left by the thousands, fearing quarantines after the emergence of clusters among FoxConn workers.

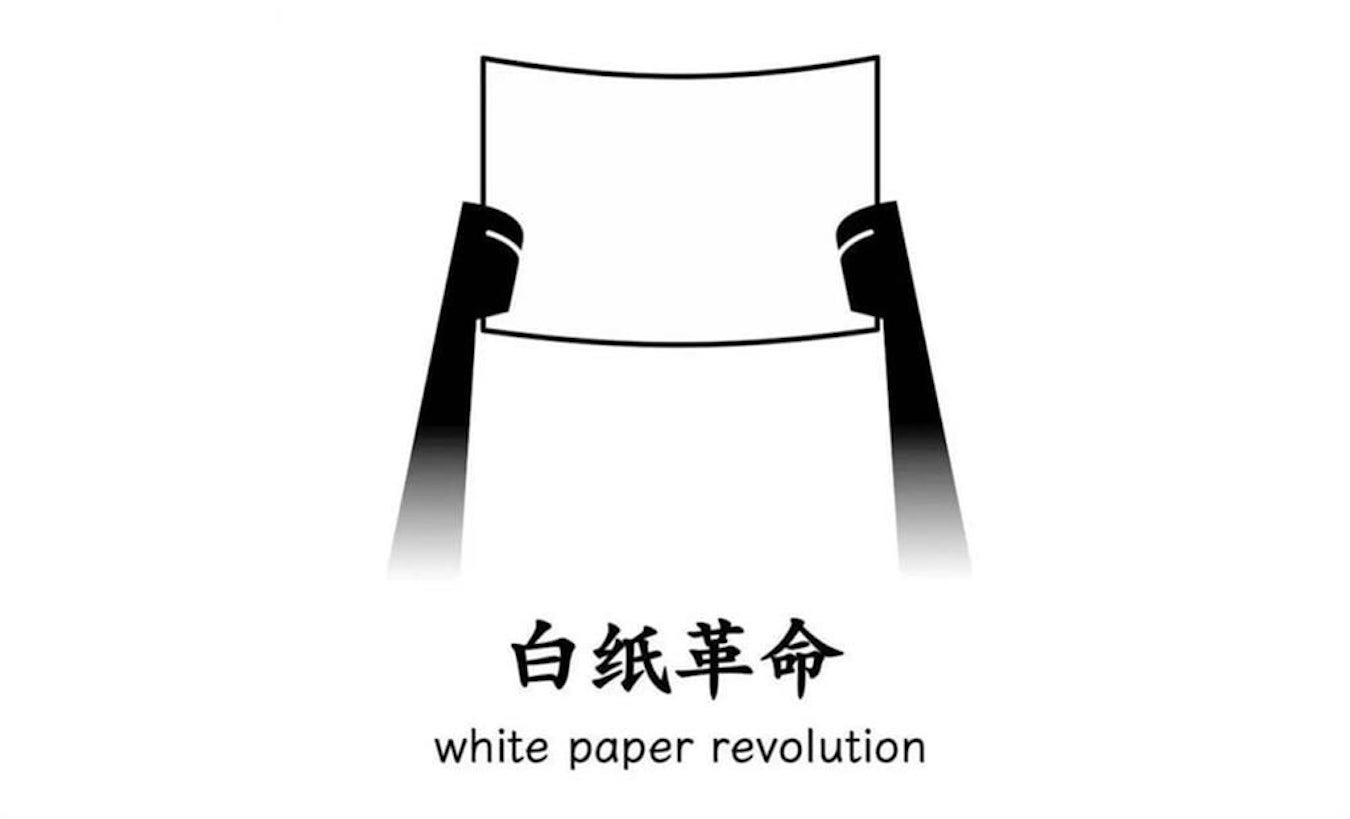

The protests have been termed the “A4 Revolution” by some. Namely, protesters have often taken to holding up blank pieces of white paper as part of their protests. This is due to authorities cracking down on signs with slogans on them.

The blank sheets of paper reflect that the message of the protest, in many ways, does not need to be spoken out loud. It is self-evident what protesters are demonstrating against.

At the same time, a blank sheet of paper can contain everything and also nothing. Certainly, the blank sheet of paper also reflects how the demands of the protests are open and abstract.

After all, there is no singular demand from the protestors, but likely a series of overlapping demands. Some simply hope for an end to restrictive rolling lockdowns that have led to food shortages even in developed urban areas such as Shanghai. Still others, as evidenced in some of the protest chants that have been seen in the protests to date, call outright for the downfall of the CCP and for Xi Jinping to step down. This, too, maybe proves quite fitting for the blank page.

This was such a brilliant video I subtitled it so more people can watch it. Beijing students’ response last night to accusations that there are ‘foreign forces’ at play in this weekend’s protests

‘The foreign forces you are talking about – are they Marx and Engels?’ https://t.co/umdFaVhz2s pic.twitter.com/RoohkFaZgE

— Cindy Yu (@CindyXiaodanYu) November 28, 2022

Likewise, the blank page proves an ironic rejoinder to the Chinese government’s fears of a “color revolution” fomented by external foreign influences, aimed at destabilizing the country. Protestors have often sought to emphasize the point that they are regular Chinese people, rather than foreign agents. White, of course, is in some sense a color while also colorless.

More generally, with the term “A4 Revolution,” one notes that social movements often take their names from everyday objects. One thinks of, say, the 2014 Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong. The name of the movement came from the use of umbrellas by protestors to deflect tear gas canisters fired by the police. Or the Milk Tea Alliance. The name of the online netizen movement between Thailand, Myanmar, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and elsewhere was drawn from the fact that all of these locations commonly drink milk tea beverages.

The commonplace nature of the objects that movements take their names from reflects how the participants of such movements are themselves ordinary people. Insofar as such objects are commodities, perhaps there is something to make of the worker as the living commodity–and under capitalism, we are all commodified. With the Milk Tea Alliance, this reflects that residents of east and southeast Asian countries are aware of the milk tea beverages of other countries due to globalization.

In acts of protest, demonstrators appropriate objects from their everyday surroundings. But the spectacular rupture of the everyday that protest movements lead to are precisely synthesized from the ordinary moments of life.