by Enbion Micah Aan

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Book Cover

“GOD IS DEAD”, Nietzsche famously proclaimed. Many atheist movements use this statement as a rallying cry, but what they often ignore is what Nietzsche said after these three famous words:

…And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?

If we actually pay attention to Nietzsche’s words, it is quite clear that he is lamenting that the Enlightenment has moved Western philosophical discourse toward secularism. What Nietzsche really means by this statement is quite clear, he is asking: without faith as a guidance and a sense of what is sacred, how can human beings carry on? In other words, without faith, without spirituality, without the belief that our existence is not simply the here and now, how can human beings be functional? How will human power restrain itself in our attempt to be god or at least god-like?

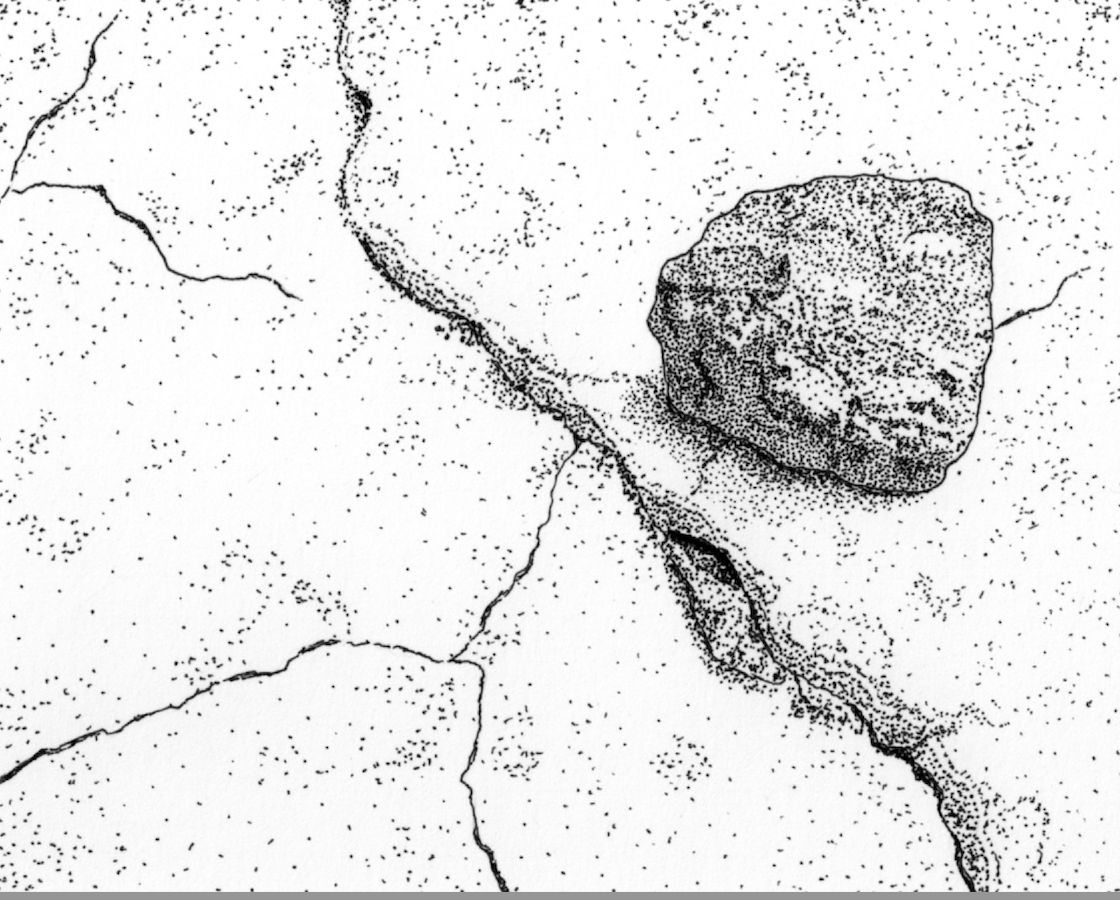

Book illustration by Judy Langemo Roth

Joshua E. Livingston’s Sunrays on the Beachhead of the New Creation, a book with 54 short stories with black and white graphic illustrations that serve the tales beautifully and integrally, deals with what it means to have faith (specifically Christian faith), and what it takes to have faith when our daily reality is decidedly secular. When secularism is practically a religion, what does it mean to believe, be spiritual, and attempt to see beyond ourselves? Does life have no meaning beyond what we are capable of understanding?

Livingston’s collection of short stories do not offer straightforward answers to these weighty questions, instead, the stories are vignettes that often express a meditative mood, a thoughtful sentiment, and sometimes our innermost thoughts and feelings. They are often quite short, some are only a few sentences – for example, the first story is a simple note a mother wrote. Some of the stories can be quite dark and nihilistic, while some are quite hopeful. A few stories are rewrites of Bible stories, updated with modern secular sensibilities. Many stories are also commentaries on our contemporary situation and timeless human condition, with a wide range of subjects, from corporate culture, Plato’s cave, and even class issues. All the stories are thoughtfully written, and they can at times, be quite abstract. Some stories are cut into different segments and placed separately throughout the book.

Book illustration by Judy Langemo Roth

Certainly, not all of the stories are literally about faith in the age of secularism, as many are more about faith in general, and focusing on one subject that would make the subject repetitive and pedantic. Instead, these concerns are often only hinted at, as Livingston seems to prefer a subtle approach for the most part. The word “secular” never shows up in the novel, and yet, reading the novel, one gets a clear sense of what the struggle is – it speaks volumes when a writer can communicate the idea without ever using the word that most aptly describes the subject. The short stories are the trees of the forest, and the ground is the struggle. The book reads much like a wandering prophet’s notebook, with big ideas about faith in small doses.

One of the questions that really stands out is, what is good, when faith is unimportant in our daily life? Can we be moral in a world of extreme moral relativity? None of the stories give us specific answers. Here, Livingston trusts his reader to answer these questions for themselves, as the stories are mostly descriptive in the sense that the characters express profound doubts about these questions. These moody stories gesture toward the post-secular insights of Jurgen Habermas, who understands the need for us to reconcile secularism with faith.

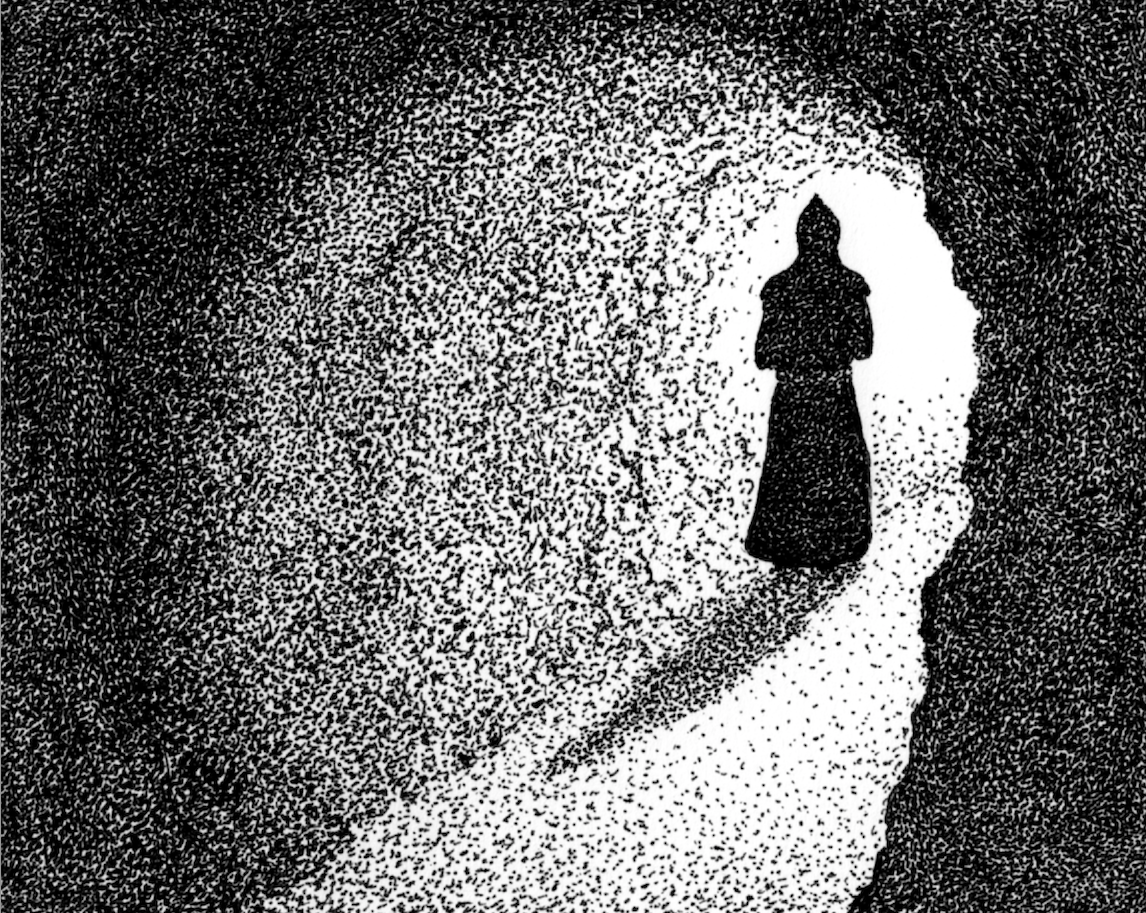

Book illustration by Judy Langemo Roth

Another reappearing characteristic is that of the use of animals in the stories. The way Livingston uses animals is quite consistent with how Christian fables use animals. The animal characters are archetypes that give us moral lessons, and this usage reflects that they are only significant when useful to humans. Using animals as mere symbols and practical use is so common for those of us in the West that we often take this for granted. However, in the pagan tradition, as well as indigenous folklore, animals tend to take a much more significant role, oftentimes having equal or even greater significance than humans.

In the ancient world of Greco-Roman culture, birds are often prophetic and are messengers of gods. For example, in the Iliad, King Priam’s prayer for his son Hector’s body after being killed by Achilles, was answered with a black eagle. Margret Robinson, an indigenous theology scholar and an activist, proposes that Mi’kmaq legends to be an alternative model to Western human relations to animals, as in Mi’kmaq tales, animals are portrayed as siblings to humans. In contrast, animals in Christian fables are merely symbols and instruments. Jesus himself gave people fish to eat, God himself instructed Noah that everything that moves is on the menu, and human beings are created in God’s image, making humanity the supreme creature on earth.

Underneath Livingston’s concerns and Nietzsche’s lament for the loss of faith in the secular world, it seems some of the Christian structure remained. This is what Norman Cohn argues – that the secular world, while without God, is structurally the same. This relationship of domination to animals perhaps illustrates this point quite well – according to USDA reports, we currently kill 235 million turkeys a year in the US, and globally, it is estimated that humanity kills 3 billion animals per day. This particular relationship of domination does not stop at animals, as we also extend the same courtesy to all of the natural world, polluting rivers and oceans, clearing forests and jungles, and pumping greenhouse gas into our atmosphere. The apocalypse, it appears, will be man-made.

Book illustration by Judy Langemo Roth

The loss of faith in the secular world could perhaps partly explain how humanity at this point in time would have what Freud calls, “death drive”, as nothing is sacred, and the loss of spirituality may very well mean unrestrained human power. However, it seems like beyond the loss of faith in the secular world, perhaps, if Cohn is correct, the secular Christian structure is also a contributing factor, and the reclaiming of Christian faith may not be enough to save us.

As a reviewer, I have the duty to inform the reader that Livingston is a friend. We met when we were both quite young, both barely in our twenties, and I was his wedding photographer. When we first met, it was immediately obvious to me that he was intellectually mature beyond his age, and he was already meditating on questions of faith, love, truth, and all sorts of weighty and complicated issues. He has always been intellectually curious and enjoys thinking about profound questions about life. His interests and sensibilities are expressed in his stories in this book. His voice is unmistakably his, and his concerns are important and deserve our attention. With any luck, perhaps, we will be able to see another book from Livingston, to further deal with the issues he might not have been able to in this volume.