by Anila S. Pan

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Jr Korpa/Unsplash

Subconscious (noun.)

Below your conscious mind; refers to a domain of experience that is hidden from our awareness, but nonetheless impacts our behavior. Sometimes used interchangeably with the unconscious.

THE SUBCONSCIOUS works in strange ways.

It lurks beneath the skin. It festers and grows and takes root. It’s a disturbing thought, truly. To think that what you cannot see is precisely what guides your behavior, grotesquely manifest in your fears, desires, speech, attachments and habits.

What of Taiwan’s subconscious? What is it that remains invisible but continues to animate the spirit of the island, along with the disconcerting truths that many of us, when confronted with, instinctively look away from?

As I reflect on this line of inquiry, I sometimes look back on a moment that left an unnerving impression. I was sitting beside a friend on a bus for a school field trip. I couldn’t remember where we went or what the trip was exactly for, though I do remember looking into the narrow gap between the two seats in front of me, peeking—uninvited—at the conversation the two boys were having on their phone. To evade intrusive ears, they had been using “Notes” on the iPhone to write and communicate on the bus. Naturally, one of the boys asks the other which girl he likes. He mentions my name as a suggestion: What about her? The other boy’s response—in tiny dark text on retina display—is the only detail I can recall from this otherwise trivial memory:

Nah, never a black.

If I had been flattered to see my name come up, that was very quickly no longer the case. I was “a black”—whatever that meant—and he could “never like” me for it.

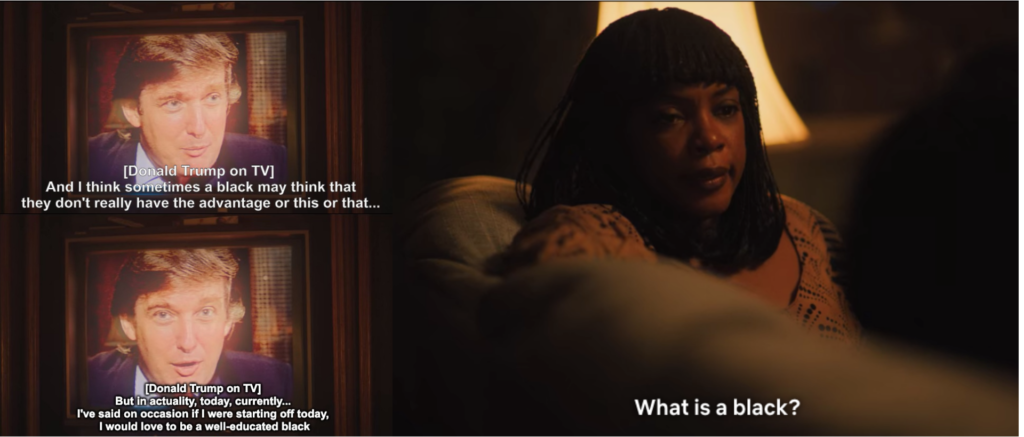

In When They See Us Episode 2, Aunjanue Ellis’s character asks “What is a black?”. Photo credit: When They See Us

However upsetting that remark might have been, I knew better than to take it to heart, though it does beg the question: what is “a black” in Taiwan? Even as a child going into High School, I certainly didn’t think I qualified. I was of mixed heritage—half-Indian, half-Taiwanese—and while my Indian features are more particular, many have trouble placing my ethnicity. That is not to say that such a label is limited to Taiwan or this specific environment: I was also classified as “a black” in Vietnam at an international school.

The Many Identities I Carry

MY SINGULAR EXPERIENCE in Taiwan involved attending a campus with a Taiwanese-majority student body, where over half of the students were local school transfers. In retrospect, I likely spent more time conversing in Mandarin with my peers than in English. My high school was a bizarre microcosm of a local Taiwanese institution attempting to pass itself off as an American school with a Western curriculum. As much as the school sought to dress itself in “American” attire with its college-oriented ethos, entrepreneurship programs and design thinking workshops, it could not protect me from the Taiwanese subconscious—a subconscious that had no conception of racism. I understood this early on and perhaps, even suffered for it. Ironically, my school shared a campus with Kuang Fu Highschool (私立光復高中) for a few years, the school implicated in staging a Nazi-themed parade in 2016, which I happened to witness through the window at the time.

In what seems like a tragicomedy twist, I carried a nickname coined by one of my closest friends: “little brown girl.” It caught on rather quickly, though it had to compete with a few other terms that I became associated with for the entirety of my time at the school.

I was a “terrorist.” I walk into a classroom carrying a bag, and someone would say “she’s carrying a bomb.”

I was also a “maid,” repeatedly told to “clean up the mess.”

I was, of course, an “Indian” who was said to “worship a cow.” On one particular occasion, a lowerclassman leaned in and sniffed, before asking: “do you smell curry?” He concludes: “you smell like curry.”

The most definitive term that was widely used to describe me was “black,” or the Mandarin rendition hei-ren (黑人). I would usually be met with a recurring fanfare of “a black person has walked into the room” (“黑人走進來了”).

It seemed to me that Arabs, Muslims, South Asians, Southeast Asians and African Americans are often conflated as the Other by virtue of associated traits—especially skin color. I am not certain of the extent to which this applies to the general population at large, but it was strikingly characteristic of young students that have only ever known Taiwan and its ethnically-Han majority climate their entire lives. To be clear, not everyone was complicit in making these comments; it was generally limited to a few of the same people—but nobody raised concerns about them either, except on rare occasions; I didn’t. It was a self-reinforcing environment, where students with some experience studying overseas also fell into the habit of using these racial terms. There were similar cases beyond the reaches of my campus as well.

I remember volunteering for a local non-profit that was distributing food for indigenous families that came down from the more remote vicinities of the mountains. A little boy noticed that I looked different, and he confronted me about it. I couldn’t remember if I told him I was part Indian, but he eventually resorted to calling me “Obama’s daughter” (“奧巴馬的女兒”) with his giggly bearing. He couldn’t have been older than 12.

“Innocent” Racism

I SOMETIMES WONDER: Is there such a thing as “innocent” racism?

I have never been consciously offended by racial remarks in Taiwan. They always seemed to have come from a place of profound innocence, involuntary unawareness and at times, raw insecurity. The remarks were intended to be funny: they were, supposedly, jokes. For the most part, I laughed along too; as a child, there didn’t seem to be an alternative as I would risk antagonizing the only group of people that I could befriend. I recall being one of the only students that embodied painfully distinctive foreign features, along with a tanned complexion that affirmed my Otherness—which was virtually at odds with my self-proclaimed Taiwanese identity. Simply put, I was the only one that looked the way I did and had “Indian blood” running through my veins. It may have also been the case that the ambiguity of my physical appearance and ethnicity made it seem as if there is a “free pass” for calling me out as a terrorist, maid, Indian or “black” because I was none in actuality. In spite of it all, I have never found my peers at fault; it seemed to me that it was more of a failure with the system in which we were being educated, an inconvenient attribute of a Taiwanese social climate that simply didn’t concern itself with questions of racism or microaggression.

While coming to terms with the “Taiwanese subconscious” was useful for surviving adolescence, I’m beginning to recognize and reckon with my own subconscious: my obsessive compulsion with putting on sunscreen on sunny days; my fear of smelling like curry, of being singled out as a terrorist suspect on public transport, and of being mistaken for a migrant worker. There is an enduring sense of unease whenever I walk on the streets or into a 7-11 because I know such perceptions would fundamentally change the level of respect I would receive as a human being—I would be seen as less than, an Other. These suspicions continue to loiter in my subconscious as the invisible, unwanted product of unconscious socialization through the formative years of my childhood. I suppose words carry weight, and they outweigh intentions.

It was the pejorative use of these terms and the reference to Indians, Muslims, Black people and migrant workers or “maids” that reflect a long-standing and arguably deep-seated perception towards these groups in Taiwan. These ideas and beliefs are not always articulated in public spaces, but children tend to mirror what they are exposed to at home or elsewhere, and in the confined rooms of certain institutions, these ideas are brought to light unfiltered. While I recognize that my peers likely harbored no malicious intent in how they referred to my identity, I sometimes wonder in what other ways these perceptions could be manifest in other Taiwanese individuals—against those who cannot easily insulate themselves with the same sort of defensive ambiguity I carry with my physicality and with the extraordinary privilege I have of being a Taiwan national who is fluent in English, conversant in Mandarin and pursuing higher education. In Taiwan, worst-case scenarios involve being shot to death by the police as a “runaway” migrant worker or being sexually assaulted as a domestic worker by your Taiwanese male employer. As grave as these incidents might seem, they occur more frequently than we might imagine.

I often hear and ruminate over arguments that cast the use of racial terms as “a display of affection,” or of how “offensive” slurs are used in tight-knit friend groups as light-hearted terms to poke fun at a friend whom you don’t share the same background with; these groups are sometimes diverse, though they can also be asymmetric in their ethnic composition. In such spaces, the use of these terms becomes “accepted” by friends on the receiving end of these remarks. To be clear, this does not refer to the “reclamation” of offensive terms by particular groups themselves; it seems to be widely acknowledged that groups of a particular ethnicity or identity are allowed to describe themselves in such terms, given the absence of noticeable or questionable power dynamics. The normalization of certain “stereotypes” or racially charged terms risk perpetuating the continuity of these stereotypes in the conventional vocabulary people share. This becomes a concern when stereotypes are inherently tied to a connotation that denigrates the Other, and when wielded by people without the lived experience of Otherness, they risk internalizing these terms without the intention to do so. You cannot separate the “Muslim” from the “terrorist” when you refer to someone with a Muslim background as a “terrorist.” This is precisely the type of normalized conceptual relation that the Chinese state has exploited to justify their internment of the Muslim Uyghur people in Xinjiang. While being called a “terrorist” by seventeen-year-old school kids may seem negligible in the classroom, the strict interpretation at the state level of the “Muslim terrorist” stereotype has very real implications. The way people frame and associate specific ideas ultimately make it easier for them to buy into narratives that facilitate dehumanization.

Reflecting on Taiwan’s Subjectivity

THE GROWING TRACTION of anti-racist movements in the United States, particularly that of Black Lives Matter (BLM) and the more recent #StopAsianHate, has given rise to transnational solidarity and earnest dialogue on related issues beyond American borders. Taiwan’s government only recently condemned the anti-Asian attacks in the U.S., and while there is little domestic coverage on the relevance of these attacks on Taiwan, local independent journalists have taken on the mantle of asserting how “Taiwan is not immune” to the universal pestilence of misogyny and xenophobia.

In Taiwan, it is hopeful to see relevant intellectual discourse come to fruition in the past few years, with observations concerning the asymmetrical power and class relations between Taiwanese employers and Southeast Asian migrant workers, and the routine exploitation of the latter. These discussions are informed by the Taiwanese experience with migrant labor and the observable dynamics at play. Though, when considered alongside the patterns of systemic discrimination in the West, this is a comparatively more recent development, which seems to be why some continue to refer to migrant workers with the derogatory short-form for foreign worker, wai-lao (“外勞”) and find it acceptable. The Indigenous community, on the other hand, has a longer, historically-established experience with racial discrimination by various settler colonizers

such as the ethnically Han people of Taiwan, which they continue to face today in the milder forms of socio-economic marginalization and insensitive language.

When it comes to racism in more general terms, as understood within certain frameworks of, for example, Critical Race Theory (CRT) or xenophobia, such an awareness feels virtually non-existent for the vast majority of Taiwanese—apart for most of the college-educated. Taiwan, and much of East Asia, is implicated in a geopolitical history of race and subjugation that differs from that of the United States; their respective historical memories are discrete. This may explain why we do not share the same vocabulary and mental schemas concerning race, as constructed in the context of the United States, when confronted with people of color that are not of East Asian origins. America’s culture of “political correctness” that is so delicately maintained is absent in Taiwan. The brutal and stubbornly persistent incarnation of white supremacy establishes a necessary caveat against the use of racialized language in places such as the United States, as to prevent the resurfacing of a historically conditioned “white supremacist” subconscious. The Taiwanese collective experience diverges with its narrative of race relations that is much less involved with the Black experience as understood in this context, which is likely what compels most locals here to act erroneously when confronted with race-sensitive encounters related to African Americans.

This may be why we continue to see blackface performances surface in Taiwan, including the viral Ghana Coffin Dance videos by dance groups Luxy Boyz and Wackyboys. Again, the reluctance to issue a public apology by these groups may also speak to an inability to grasp the weight of the violence perpetrated by their actions. Likewise, when the Oprah interview with Meghan Markle and Prince Harry was released, with Western media’s focus on Meghan’s claim of how concerns were raised by royal members about her then-unborn son’s skin color, many Taiwanese social media users ridiculed the development as trivial and a non-issue, and very few expressed sympathy.

公視新聞網 PNN Thread on Meghan Markle on the Oprah Show, from March 8, 2021

Colorism is deeply pervasive in Taiwan, and in my experience, there tends to be no filter in conversations when it comes to pointing out one’s skin color. An unintended tanning session would provoke remarks in my extended family circle such as “you’ve become more dark/black” (“你變黑了”). Conversely, when my skin tone returns to a fairer complexion, I would be told “you’ve become whiter, more beautiful” (“你變白了,比較漂亮”). Conversations with my Taiwanese friends reveal they’ve had similar experiences as well, despite being fully Taiwanese. A classmate of mine was nicknamed “blackie” by his close friends, for being tanned and darker than the average Taiwanese male. Sometimes he was called “African” (“非洲人”).

I sometimes wonder how my father feels in Taiwan: a South Asian with his deep ebony skin and broken, passable Mandarin. I distinctly recall a moment when a friend of our relative commented on how my father was “so black” (“好黑哦”). He repeated it at least twice, to which my father had no verbal or physical response to. To be fair, such remarks are not definitive of my father’s experience in Taiwan; for much of his life, he has been showered with praise for his Chinese abilities as an “Indian,” and despite the dark shade of his skin, he has been described as “handsome” on multiple occasions. After all, my Taiwanese mother agreed to give her hand in marriage to this foreign man. While she has never expressed an issue with the color of my father’s skin, it has not prevented her, my grandmother, aunts, great-aunts and the like from articulating a preference for my fairer complexion. One might also wonder if different standards for beauty are imposed on men and women in Taiwan.

While some might be tempted to highlight certain forces such as “white supremacy” in reinforcing these commonplace East Asian standards for color and beauty preferences, it overlooks sensibilities that may potentially have regional origins. Ancient Chinese “beauties” as depicted in paintings that date back centuries portray women with pale, paper-white skin. The use of white cosmetic powder for face-painting was also a common custom by women in the upper echelons of imperial Chinese society and was indicative of social status. These practices persisted before recurrent contact was made with the European continent and before noticeable Western influence took hold in the region. That is not to say being a White person doesn’t come with a certain degree of privilege in contemporary Taiwan.

Taiwan’s Place in a Globalizing World

TO BE A CHILD of globalization comes with an inconceivable sense of perpetual displacement—a disturbance of sort: the fault lines between distant societies or “civilizations” are deeply felt in the space you occupy, the people you interact with, and the commonplace cross-cultural misunderstandings you observe.

Taiwan carries a deeply aspirational presence in the international community and pleads to be recognized for its value as a member. The island has defeated staggering odds in the face of a global pandemic and it continues to fight for a dignified place in international forums, including the World Health Organization (WHO). While the country pursues its noble objectives of securing a justified, global presence against less sympathetic forces, it might be fair to say that it doesn’t preclude Taiwan from engaging in the self-reflection of its own development.

The Taiwanese subconscious and the community at large subsists on a life of its own, removed from the context of the historical memories and systemic realities of hyper-diverse societies in the United States and elsewhere. While being referred to as “Obama’s daughter” would be considered a compliment under drastically different circumstances, it becomes difficult to see it as such when the remark was more of an allusion to my skin color—to racialize my identity. There is a crucial question about confronting the disconnect between Taiwan and the world, but this is an incredibly perplexing task when you consider the comparable need to, on the one hand, prioritize domestic issues that touch the lives of Taiwanese people and on the other, preserve the diversity of Taiwan’s vibrant cultural landscape that has historically suffered from colonial suppression. Responses to these questions have taken the form of the Tsai administration’s recent “Bilingual Nation by 2030” policy and the integration of Southeast Asian languages into national curriculums, and while the former has received a number of well-reasoned criticisms, the many questions of globalization and its implications should not be lost on us. What is the place of working migrants and immigrants in Taiwan? What are their stakes in our political and policy-making process? What would Taiwanese citizenship mean for immigrants?

The acute anxieties of an increasingly connected world are symptomatic of a transnational phenomenon that is not unique to Taiwan, especially with respect to issues of racism. My first year in college at Sciences Po brought to the surface intriguing tensions between France’s “race-blind” culture and anti-racist movements in the United States; I watched, half-amused, as the French professor leading our “Theater Workshop” passionately insisted on performing blackface, in spite of unrelenting protest from the students. Another professor was quoted telling a black student that “it didn’t matter if he worked during the holidays because coming from the Outre-mer (overeas) he was already used to slavery.” More recently, I witnessed a fellow French student on social media launch a tirade against anti-racist discourse and the conception of “white privilege” as being inconsiderate to the sensibilities of white French individuals. I had lunch with this student on the first day of orientation week, and I found him rather thoughtful and sweet, though just a little soft-spoken.

Overcoming the Subconscious

A RECOGNITION of the Taiwanese subconscious does not absolve anyone of how they treat immigrants, nor is it an indictment of how they see the world. My use of the term “Taiwanese subconscious” is also flawed: it is a deeply imperfect generalization grounded in my personal understanding of and limited experience in Taiwan, and it should be noted that the real perceptions held by Taiwanese people may vary considerably across specific settings and individual subjectivities. It is unlikely for one to encounter the frequent use of racialized expressions in the enclaves of English-speaking and expat communities in Taipei.

As with all affairs involving the mind, overcoming the subconscious is demanding. That being said, none of this is to suggest that Taiwan is an inhospitable place; it proves to be quite the opposite. Some of the kindest, most generous people I’ve encountered have all been Taiwanese. I have been, time and again, moved by little acts of incredible kindness that I have yet to experience elsewhere. I never seem to have an umbrella on me whenever Taipei decides to rain, but on one December day outside the Taipower MRT station, a female stranger comes over to shelter me with an umbrella, assuring me to “hold on” because “the pedestrian light will turn green soon.” There is no end to the list of moments during the pandemic where spare facemasks were readily offered by strangers when someone else was in desperate need of one. The world could use more Taiwanese hospitality. We should, however, remain cautious: Taiwan is such a young democracy, and it maintains a relatively homogenous population that is beginning to change. Spectating from afar the grim struggles of democracies in other parts of the world as they buckle under the crushing weight of anti-immigrant sentiments, it makes you wonder if Taiwan will suffer the same fate—of becoming consumed by the primordial instincts of “in-group” thinking when it comes to the imagination of Taiwanese identity. After all, the subconscious is invisible, and rarely does it make itself known unless otherwise provoked.

The possibilities of meaningful cultural exchange and the prospects of a cosmopolitan lifestyle, as informed by activities such as “globe-trotting” and studying or working overseas, are often restricted to the few who can travel and afford the experience. Likewise, the objective possibility to experience mingling, mixing and sharing in diversified environments with people outside one’s “tribe” is not the same as the ability and desire to do so. How do we create conditions for diversity to flourish, for migrant workers and other foreigners to be accepted into Taiwanese society not as an Other, but as people with unique lived experiences? Do Taiwanese people have an ethical responsibility to be informed of the lived histories of marginalized groups from beyond the island and to be socialized accordingly to behave with mindful linguistic awareness? Even then, there are specific perceptions attached to the intersection of class and ethnicity that exists on a separate level when it comes to the recognition of migrant workers. How can we communicate a positive reinterpretation of labor performed by Southeast Asian migrants as work that is dignified? How do we nurture an emotionally safe learning environment for migrant children or children of mixed backgrounds? Education plays a vital role in facilitating the rise of these conditions, though Taiwan has a long way to go in terms of reforming its public education system.

At the recent Taipei community forum on #StopAsianHate hosted by Taiwan Mixed, I had the rare opportunity of listening to the experiences of fellow community members. One Taiwanese participant in my discussion group spoke about the discrimination his father faced at school as a half-Indigenous man and how in stark comparison, the participant now proudly claims his quarter-Indigenous heritage. In another humbling anecdote by the same participant, he recalled his experience as a young man who often looked down on migrant workers and their “loud mannerisms.” He explained that he thought of them as the Other, a group that he sought to avoid whenever possible. As he moved on to college, he learned about the realities of migrant workers in Taiwan, the nature of their work and how they are, in turn, treated. He now understands that the beliefs he once held were misguided and now has a changed mindset. I emphatically agree with the words of a British writer in our group as she comments on his experience:

“You show us, change is possible.”