by Nelson Moura

語言:

English

Photo courtesy of Sorry Youth

THERE’S A LONG list of events people would likely highlight in 2021. Possibly the impressive quick roll out of the first COVID-19 vaccines, an Evergreen cargo ship getting stuck in the Suez Canal and paralyzing global trade, the fall of Kabul, or the Tokyo Olympics.

Well, for me, one of those key events was the launch of “Bad Times, Good Times’” the third ever album of Taiwanese indie-rock band Sorry Youth (拍謝少年).

The garage rock power trio has long spearheaded Taiwan’s indie native Hokkien scene first with their 2012 debut album “Seafood,” then with their 2017 “Brothers Shouldn’t Live Without Dreams” second album—which won a Golden Melody Award and a Golden Indie Music Award—and now has released their third complete studio effort.

Photo courtesy of Sorry Youth

Releasing an album almost every five years is not a very prolific work rate—understandable as the trio maintains other day jobs—and considering their commitment to singing in the island’s Hokkien or Southern Min, this makes each of their only three albums an even more precious item.

Picking their name as a tribute to noise rock legends Sonic Youth, the band comprises Weni (vocal, guitar), Giang Giang (vocal, bass guitar), and Chung-Han (vocal, drum), none of whom majored in a music-related department.

Still, they decided it was meant to be and formed Sorry Youth in 2005 after inspiration arose from their experiences in Taiwan’s oldest music festival, Spring Scream.

Although having started their career mainly playing instrumental rock, they soon pivoted into writing their own music with lyrics in Hokkien, inspired by local legends Wu Bai (伍佰) and Lim Giong (林強).

Making justice to their name inspiration, their albums are a cacophony of youth vitality and loud but carefully controlled guitar distorted feedback.

Their first two albums could reflect the experiences of lost youths wandering either in the beaches of Kaohsiung or the urban sprawl of the Taipei metropolis, which the growing drum power of “Station 17” or the mesmerizing music video of “Undercurrent” beautifully exemplify.

Their third album comes as a more peaceful effort, as if the calm on a Taiwanese seaside area post-typhoon, were sprinkled with dead pufferfish.

Photo courtesy of Sorry Youth

As the band explains the album’s Hokkien pronunciation can be explained as “pháinn-sè” (“Bad Times”) a common auxiliary verb used by the general public, while “hó-sè” (“Good Times”) has two different meanings when used in two opposite situations.

“Hó-sè can be used to describe a situation when things are going smoothly, and conversely, it can also be used sarcastically on a messed-up situation,” the band explains.

“In life, good and bad things happen in turn. They are just different possibilities of life.”

While the previous “Brothers Shouldn’t Live Without Dream” attempts to catch the energy of Sorry Youth’s live performance, “Bad Times, Good Times” works as a collection of “short stories” the band explains.

After two busy touring years, the group began to do some songwriting and other preparation works for their upcoming third album in early 2020.

Not long after the pre-production work started a small coronavirus started wreaking havoc globally with all live gigs and music festivals in Taiwan temporarily canceled or postponed.

This incidentally gave the group a lot of time to arrange these new songs one by one, the result being nine songs about “lovers, family, friendship, environmental protection, solitude” or “nine different people meeting at the same corner discussing the good and bad in their daily life”.

The group’s first album of “Seafood”, was mainly created from Sorry Youth’s main three-piece instruments and the songs progressed as the natural flow of their musical instinct, “Brothers Shouldn’t Live Without Dreams” added Taiwan’s traditional Beiguan music sounds and Western trumpets to the mix.

Photo courtesy of Sorry Youth

“When we started to make ‘Bad Times, Good Times’, we decided to even widen the perspective of music by layering more music elements, such as the synthesizer, piano, and electro beat. So some of our songs might sound like a bit of shoegaze, post-punk, slowcore, and even dream pop. But we think we could still be categorized as alternative rock”

With the young working-class members and their travails as the main axis of the album, “Bad Times, Good Times” starts off with a softer “Love Our Differences” to jump to three powerful collaborations with different indie Hokkien mainstays.

The first, the swinging “Justice in Time” with Ke Jen-chien (柯仁堅) the veteran singer of legendary underground Taiwanese band LTK Commune (濁水溪公社), the electronic tint herd “Walks of Life” with Chen Hui Ting from synth-pop group Tizzy Bac and “Nightmarket” beautifully complemented with the soft dreamy voice of actress and singer Jen Jen (余佩真).

The History of Taiwanese Hokkien Rock

SORRY YOUTH’S body of work can be seen as another major stepping stone into the indie history of music in Taiwanese Hokkien, a segment of Formosan music long view with suspicion and prejudice.

Taiwanese Hokkien, also described as Hoklo or Southern Min Chinese, is a dialect originating from the Fujian Province in China, which spread to the island in the late Ming Dynasty and became the most frequently used language following classic Mandarin Chinese.

The naming itself as Taiwanese Hokkien is contentious considering the great diversity of dialects and languages spoken in a 32,260 square kilometers island with about 23 million people about the same size as the Netherlands.

One just has to consider that each of the island’s Indigenous ethnical group speaks a distinct language that generally is unintelligible to other groups, with Hakka, Cantonese, different provincial dialects brought by mainland incomers and even Japanese all blend together in the Portuguese-named Formosa (Beautiful).

Photo courtesy of Sorry Youth

Distinctly different from Mandarin Chinese, Southern Min has five to eight different tones, depending on the variant, with Hokkien dialects in Mainland China and Taiwan tending to possess seven tones, whereas Hokkien dialects in Southeast Asia tend to have six.

It’s tonal variety puts it below the impressive nine tones of Cantonese but above the standard four tones of Mandarin, varying from High Level tones to High Falling tones, or Low Rising Tones.

This becomes clear when you contrast the softer term for music in Mandarin—音樂 Yīnyuè—with the stronger Im-ga̍k in Hokkien.

According to Wang Wanzhi in his “Discussion on beauty and charm of the tune of Hokkien song” research paper, the dialect’s generally deep and passionate singing trembling tones are “widely used to convey sorrow and confusion in the song of life emotionally,” with some songs “showing Fujian and Taiwan people’s spirit of unremitting struggle”

“The trembling tone is generally deep and passionate singing of the song is widely used to convey sorrow and confusion in the song of life emotionally, but also there are some songs to express inspirational thoughts, showing Fujian and Taiwan people’s spirit of unremitting struggle,” Wang states.

“Traditional Taiwanese songs always reflect tragic characteristics, highlighting how local people in the modern city indulge in feasting frustration” and “urban life full of pathos and helplessness”.

As one of Taiwan’s most common languages, the progression of Taiwanese Hokkien’s use in popular culture has greatly increased since the end of the 38-year-long Martial Law in 1987 and the end of a period where culture was repressed in favor of the dominant mainland culture.

The KMT government promoted Mandarin while suppressing the use of spoken Taiwanese Hokkien or Hakka in schools or in official settings was forbidden, with violations possibly resulting in physical punishments, fines, or humiliation.

The constitutional reforms in the 1990s helped a resurgent mother tongue movement and a revival of Taiwanese Hokkien.

“When growing up as a student at school, the KMT government ignored the fact that Taiwanese languages are composed of Taiwanese Hakka, Hokkien, Mandarin, and Indigenous, etc. They forced all the students to learn Mandarin as the only written and spoken language,” the group noted.

“However, Taiwanese Hokkien used to be referred to as ‘Taiwanese language’, since it was the most spoken language before the KMT came to Taiwan some 70 years ago”.

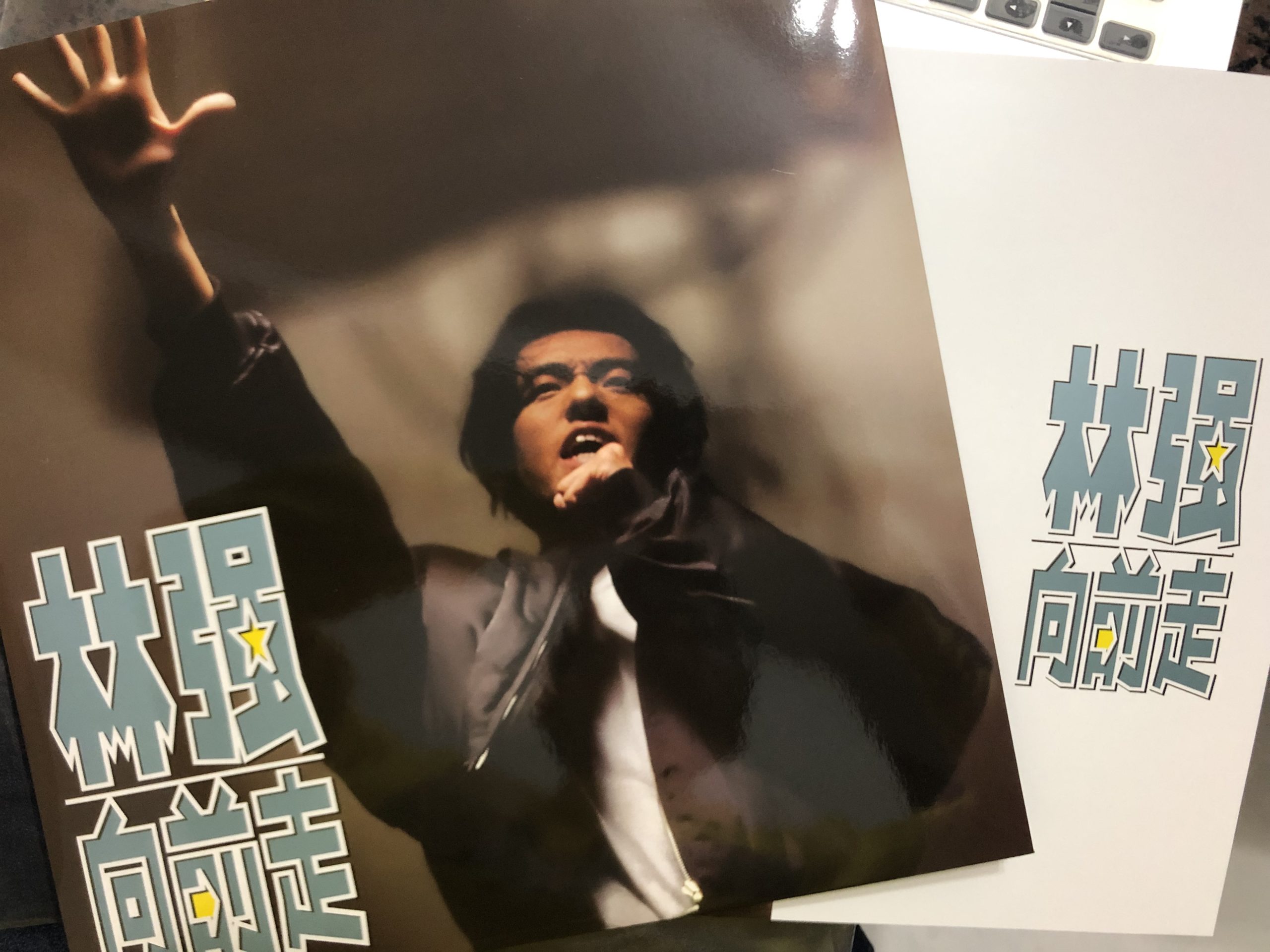

Cover of Lim Giong’s album, ‘Marching Forward’

Local dialects dominant in the “Benshengren” Taiwanese—descended from the waves of Han migration in the hundreds of years before the Kuomintang came to Taiwan—have for long been relegated to a secondary role.

Hardcore Hokkien-speaking gangsters in triad flicks such as Monga or the Gatao trilogy continue to play to the stereotype of Taike betel-nut chewing lower-class hardened criminals making fun of Mandarin speakers softer vowel use.

However, young college graduates have rowed against the tide and insisted on speaking Hoklo as part of concerns that the language and related culture will become extinct.

Music has played a considerable part in the revival of the use of Taiwanese Hokkien since the 1990s, with iconic names such as Jeannie Hsieh, Lim Giong or Formosa’s king of rock Wu Bai.

His seven-minute smoked filled the title song for the 1992 Taiwanese crime film Dust of Angels’ by Hsu Hsiao-ming, manages to effectively capture the film’s feeling of urban erosion and the change of values of the times, with a smooth bassline and strong singing.

The song embodied the “Taike” archetype, a term meaning “Taiwan guest” but basically representing the notion of something unmistakably Taiwanese. The term was usually used to denote the benshengren in a derogatory sense, to describe Taiwanese as uncouth and uneducated.

Music video for Wu Bai’s Dust of Angels

As with many derogatory terms it ended up being used by the targets themselves as a form of empowerment.

Dust of Angel’s theme actually Wu Bai’s first major commercial music release and featured two of the three members of his band, China Blue, with the Taike icon ending up releasing an impressive 26 albums.

Lim Giong is known for his electronic music work for directors such as Hou Hsiao-hsien and for having an extensive body of work in Hokkien, including his highly successful “Marching Forward” from 1990.

A highly successful album that sold over 400,000 copies, “Marching Forward” displayed a vast array of love songs centred on observations of the day-to-day reality of the life of 1990s Taiwan, be it schools, military service or the first thought of arriving for a new life in Taipei by train from the countryside.

“One by one high-rise buildings, I don’t know how many fools like me live there,” Lin sings in this known Hokkien anthem.

Indie-rock mainstay May Day (五月天) originally sang in Taiwanese Hokkien, but later switched to singing in Mandarin to achieve mainstream pop success. Still, they helped push the genre forward, even if later veering award more mainstream content.

Changing Trends

WHAT ABOUT more contemporary bands? With just two impressive albums—”Cartoon Character” from 2017 and “We’re Getting Married Later” from 2019—the southern Taipei-born band EggPlantEgg (茄子蛋) has offered an incredible array of modern take on the genre’s soulful indie rock traditions, with songs such as “Back Here Again”, “Waves Wandering”, or “Lover, you are greater than I thought”.

Made up of lead vocalist Ng Ki-pin, guitarist A-ren Tsai, and guitarist A-der Hsieh, burst into the Taiwanese scene with the power of their seven-tonal music.

Using renowned Hoklo speaking actors in beautifully produced music videos by Spacebar productions, such as Chen Jin Gui or the late Wu Pong-fong in their heartfelt representations of gaming and hard-drinking middle-aged wastrels, drowning their sorrows of unrequited love and brotherhood in worn-down neighborhood KTVs.

The members of EggPlantEgg. Photo credit: EggPlantEgg

Hokkien does not have a unitary standardized writing system, in comparison with the well-developed written forms of Cantonese and Vernacular Chinese.

It is written primarily in the Latin alphabet in a system known as vernacular writing or Pe̍h-ōe-jī, with EggPlantEgg’s music videos showing song lyrics both in standard Traditional Mandarin and in Taiwan’s Ministry of Education-developed Romanization system for the language.

The vast majority of EggPlantEgg’s music videos have also been updated over time to carry English subtitles showing a concern in allowing international audiences to understand the Hoklo lyrics.

Few music productions have so much care in presenting the language, all of it with sweeping guitar solos, rapid changes between soft whispered Taiwanese lyrics to emotional singing on the sorrows on the downtrodden under the yoke of an oppressive cruel, and material society.

“In this turbulent society, how is one to bloom?” Ng sings in “Waves Wandering”.

This plays into the common Hoklo ballad trope of love lost and wrong life choices. There’s just absolutely no middle ground, it’s either success or complete and abject failure. Mostly failure.

Photo courtesy of Sorry Youth

Success stories hardly make good content for ballads, but it’s exactly a success story what the progression of Taiwanese Hokkien rock shows in the last 30 years since it left the marginalized corner it had been sent to.

“Our grandparents and parents actually speak Taiwanese as their mother tongue, we usually talk in Taiwanese with our close family. But due to the policy of speaking Mandarin, a lot of youngsters from our generation are gradually losing the ability of speaking their mother tongue,” Sorry Youth expressed.

So for the group, making songs in Taiwanese is a way to depict the story of Taiwan and a bridge to communicate with the past and future by singing Taiwanese in the present.

“We’ll surely keep making songs in Taiwanese to communicate with the world.”

As Sorry Youth sings in “Undercurrent”, it is if as the language itself is screaming at the crashing waves, “Thiann, lán ê kua-siann, kā gún ê kòo-sū, tshiùnn hōo lí thian (Hear the people sing, Let our singing tell you our stories).”

Nelson Moura is a Portuguese journalist previously based in Taiwan and currently in Macau, with a focus on gaming, politics, crime, tech, business, social issues and the occasional music article.