by Enbion Micah Aan

語言:

English /// 中文

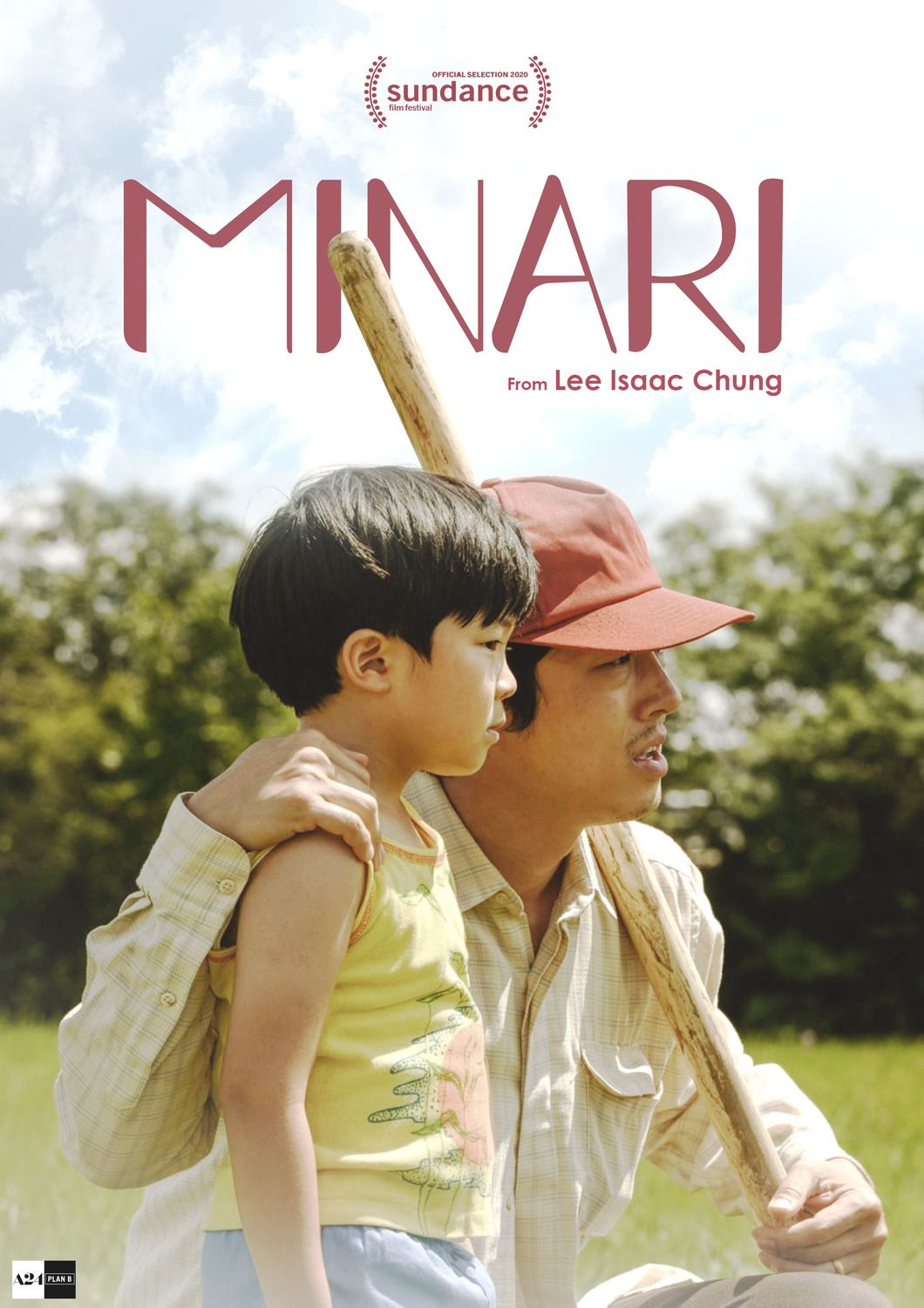

Photo Credit: Minari

IF YOU ARE like me and consider Crazy Rich Asians one of the worst Asian American films ever made, you might very well enjoy Minari. One could say Minari is a perfect counter to Crazy Rich Asians in contemporary Asian American cinema. From its subject matter to its relation to whiteness, Minari stands in the polar opposite end of Crazy Rich Asians. Where Crazy Rich Asians are about the 1%, Minari is about the 99%. Where in Crazy Rich Asians, whiteness is arguably the characters’ aspiration, Minari’s characters simply want to survive and live in their realities. Where Crazy Rich Asians designate rambunctiousness and extremities as virtues, Minari seeks balance.

Film still

Minari is about a Korean immigrant family in Arkansas in the 1980s. Jacob, played by Steven Yeun, is the father. Jacob bought a farm with his savings and his hopes that the farm will pay off drives the story. Monica, played by Yeri Han, is the mother. Monica is not nearly as enthusiastic about the farm as Jacob, misses her Korean church community in California, and would like to move back. Ann and David, the children, are played by Noel Cho and Alan S. Kim. Both children are important characters, but David’s heart condition takes center stage. Soonja, Monica’s mother, played by Yuh-jung Youn, comes to live with the family in Arkansas because of David’s condition and the fact that both Monica and Jacob have to work as chicken sexers, people who pick out male chicks to be killed in chicken farms. And, there is Paul, played by Will Patton, literally a cross bearing Christian who helps Jacob with farmwork. It is most likely intentional that the most Biblical names are the same characters who believe in the farm the most.

One of the sure signs whether a film has succeeded or not is acting. Lee Issac Chung’s Minari, if anything, achieved quiet, subtle, yet powerful performances that are in perfect balance. This is effectively true of every character in the film. When Monica and Jacob fight, we see tears hanging in their eyes. Had Yeun’s or Han’s voices trembled a bit more or a bit less, or if their faces expressed a little more or a little less, these innermost emotions would not have been achieved.

This is also true of the child actors. Ann was the older child and had to take on more responsibilities, and yet, she remains a child even in the time of taking on adult responsibilities. Had Cho portrayed Ann with just a bit more or less maturity, the character would not have worked. Had David’s angry reaction to Grandma Soonja’s jokes about him wetting the bed been just a bit more expressive or less expressive, the performance would not have worked.

Grandma Soonja, perhaps the most expressive and humorous character in the movie, never crosses the line of being a caricature, but had Youn’s performance been weak, the character would not have been funny or expressive. And Paul, a devout Christian who talks in tongues also never crosses into a liberal stereotype of a Christian from a red state, but again, if Patton’s performance was not as skilled, the character would not have worked. When it comes to the actor’s performances in Minari, Byron’s words come to mind:

One shade the more, one ray the less,

Had half impair’d the nameless grace

It’s hard to believe a film that explores such timeless themes, such as family, diaspora, and community, would generate controversy, but there was nevertheless controversy around its Golden Globe nomination. Many Asian Americans have voiced discontent with the fact that this film was nominated under the category of “Foreign Language Film”. The negative response to this is justified, since, as a “Foreign Language Film”, Minari is not eligible for awards in the acting categories under the awkward awarding system of the Golden Globes. That the primarily Asian cast members in an excellently acted film are not eligible for the awards is understandably disappointing, and all of us who enjoy and appreciate the craft of acting should take offense to this fact. And, of course, to categorize a Korean American film as “foreign” is yet another example of Asians being perpetually foreign in America. This has already been remarked on at length.

Film poster

Racism aside, this controversy also highlights the cultural hegemony and economic dominance of Hollywood. Movies and their auxiliary products are a major US export, and Hollywood is how the US exerts its cultural dominance globally. Having a “Foreign Language” category gives the Golden Globes a veneer of tolerance for international competition, while forcing English language foreign films from non-US Anglophone nations such as the UK and Australia, to compete with Hollywood’s own films. Hence, the Golden Globes is caught in the contradiction of having to impose American cultural hegemony while the structure fails to recognize non-white Americanness.

Given the controversy, it is worthwhile to examine how Minari treats racism and whiteness. Unlike more conventional treatment of racism, where overt racism is portrayed, and condemnation and comeuppance of racist characters is required, Minari’s approach to this is much more nuanced. For the characters in Minari, racism and whiteness are simply present, like the air we breathe or the water we drink. However, this is not to say that Miari ignores racism, but rather, its treatment of the racist ideology is not condemnation but understanding. For example, when white characters committ what we now call “microaggressions”, their portrayal, though brief, never denigrates humanity—as opposed to, for example, the cartoonish racists in Get Out or Django.

I suspect that many mainstream audiences would find this treatment of racism disappointing, and they’d prefer how, for example, in Crazy Rich Asians, that a cartoonish racist character is immediately punished. Yet, this treatment is perhaps more realistic in terms of how racism is typically experienced. It also highlights the limitation of conventional portrayal of racism since American media, in films or news, tend to only focus on dramatic events centered on racist individuals who live up to overt racist stereotypes, and discussions around racism are only worthwhile only when someone is killed or badly injured.

Ultimately, what the controversy robs of us, is the fact that race, racism—and deeply-rooted issues regarding Asian Americans’ discomfort with perceived foreignness—take center stage when it comes to Minari. Minari deserves to be talked about on its own terms, as a beautiful piece of art. Instead of outrage, perhaps, we all should learn from Minari, to speak and act in challenging situations with balance and grace.