ASTROJOKE

語言:

English

Photo credit: Film still from Made in Hong Kong

STARTING FROM the Umbrella Movement in 2014, the outpouring of political creativity in fields ranging from independent documentaries, films, animations, comic books, performing art, and novels has brought Hong Kong to the spotlight, especially in Taiwan.

I departed from Hong Kong and started my university life in Taiwan in 2022. Colleagues, punk friends I met in CD stores, artists, teachers, taxi drivers–almost all Taiwanese I encountered and talked with are highly aware of the social situation of Hong Kong.

“Did you notice after Tsai Ing-wen won the 2020 presidential election there was a drastic decline of Hong Kong social movement videos in online platforms and news reports?”

“Every time we watch the police shouting and hitting Hongkongers we are shocked and furious. Why can they be that violent?”

“I have watched Revolution Of Our Times! I really appreciate Hong Kong people. They endured a lot.”

But what they don’t really know is how in the course of the past few years, a cramped concrete jungle squeezed out loads of trauma and conflict. , At this juncture, Hong Kongers set themselves apart from the high wall, cultivating flowers between narrow gaps. Unsurprisingly, most Taiwanese recognize Hong Kong social and political context through “Heideggerian “at-handedness” (Heidegger, Martin. Sein und Zeit, S. 13.)and the lens of “spectacle”. Moreover, their focus remains on the 2019 anti-ELAB Movement.

For the sake of historical reenactment, it is my responsibility to take absentees back to the scenes. We cannot see the Hong Kong social movement context through a freeze-frame, it is always moving like “the horse in motion”(1878). As such, here I will aimshow you the course of Hong Kong’s social movements from the late 1970s Yau Ma Tei boat people to the 2019 protests. In order to get close to the thorough picture of Hong Kong, we are going to dive into some documentaries and films which mark regular people’s lives as they intersect with macro-political history.

Under Tyranny, the Genuine State of Existence of Houseboats, Housing Estates

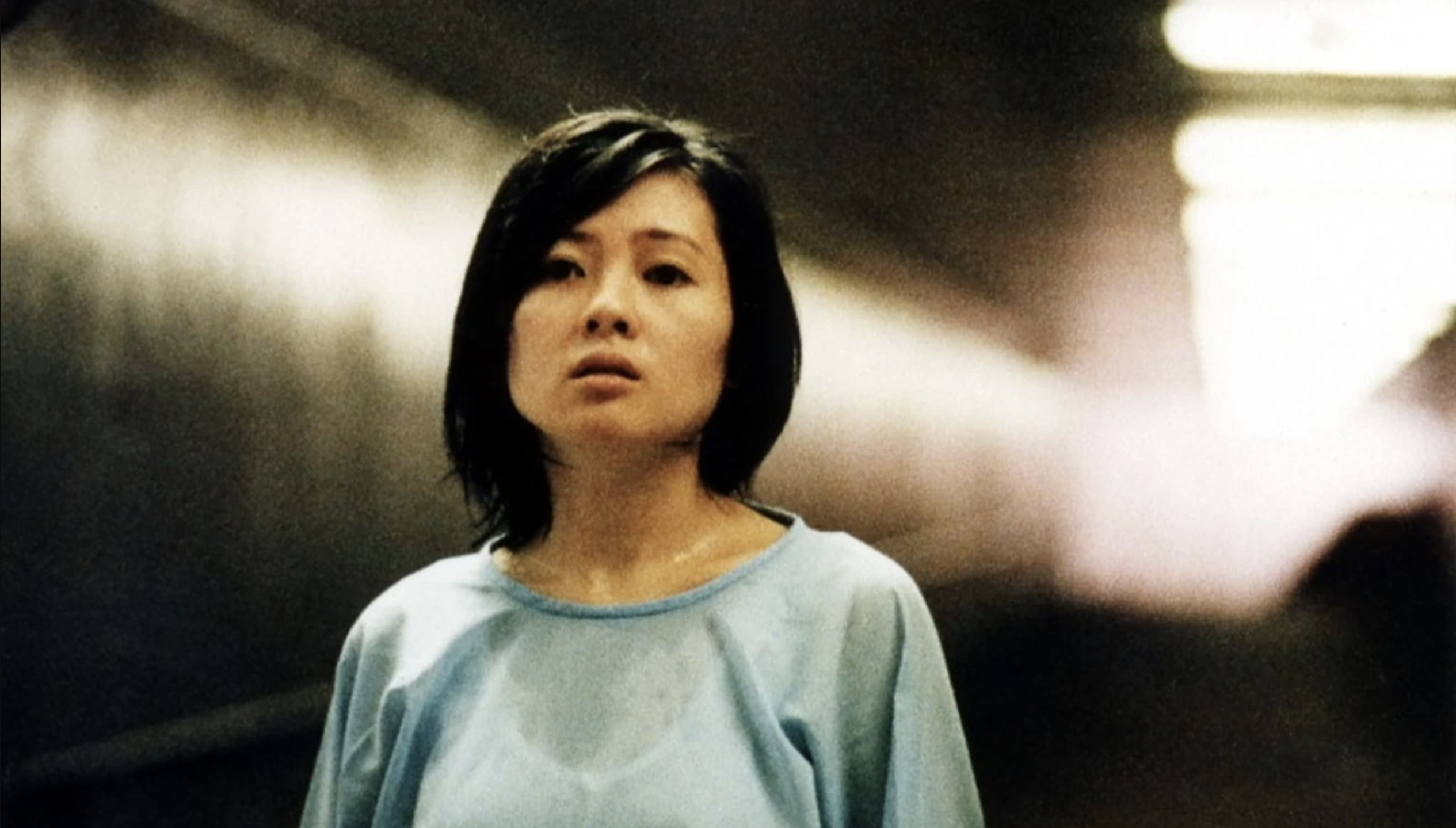

IN 1999, Ann Hui directed and produced a film called Ordinary Heroes. This was during the second year of the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong from British to Chinese control. While one of the Hong Kong New wave directors, Hui frequently sought to raise social awareness and challenge authority.

Film still from Ordinary Heroes

In the late 1970s, many fishing boats moored in Yau Ma Tei Typhoon Shelter. Due to extreme weather and poor living conditions, fishermen couldn’t fix the boats and their sewage systems, so they had to give up fishing and go ashore to work. Their education level was low and so they could only engage in labor work. Dilapidated fishing boats became their shelters, so there were loads of “boat housing” during this time.

The story begins with Sow Fung-tai, as a “boat person”, who lost her memories and needed to recall the past. Hui elucidates the story by describing her experiences.

The film proved full of protests and voices against the government. In this sensitive and censored era, Hui depicted Hong Kong social movements in the late 1970s to 1980s ranging from mainland wives’ rights, the Yau Ma Tei boat people’s welfare, and the despair of activists after the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

Before 1997, Hong Kong people focused on humanism instead of localism. No matter what, if there is inequality towards a group of people, activists fight for them against authority.

By using a compound layer-by-layer structure to deal with the theme, Ann wandered between reality and fiction. Sometimes we see Franco Mella (featured by Anthony Wong), Sow Fung-tai (featured by Loletta Lee) engaged in a sit-in outside the Government House, sometimes we see Ng Chung-yin (based on Mok Chiu-yu) narrating Revolutionary Marxist League member Mok Chiu-yu’s stories on the street like a Temple Street fortune teller.

Although this film is suffused with political issues features social activists, they are merely the background. The director focuses on the genuine existence of humans in a turbulent society society, and she is not interested in criticizing politics. Father Franco Mella naturally walked through the Legislative Council and engages in a sit-in and hunger strike for the mainland refugee moms. Under the breeze and sunlight, birds sang and flew on top of Father Kam’s shadow. When Yau Ming-foon chatted with Sow Fung-tai inside the boat, the cameras shakes a bit and the wooden board creates the mild sound of a crack.

The same idiosyncrasy can be seen in Made In Hong Kong by Fruit Chan. This time we shuttle between public housing estates. After returning to our motherland, we project our resentments to China. We blame injustice on our masters whoever they are. You can realize the subtle but conscious change from humanism to localism after watching these two films. In Ordinary People, the bittersweet affair between Sow Fung-tai, Lee Siu-tung and Yau Ming-foon is under the glory of scarification, the unsound and intangible illusion of recklessly fighting for democracy. In contrast, Father Kam manifests his symbolic identity.

He has lived on the boat for a long time, advancing and retreating with the grassroots. He is practicing his beliefs in another form. Until the 1997 Handover, we no longer have the same spirit as Father Kam, we are just ordinary people falling and stumbling in a chaotic abyss.

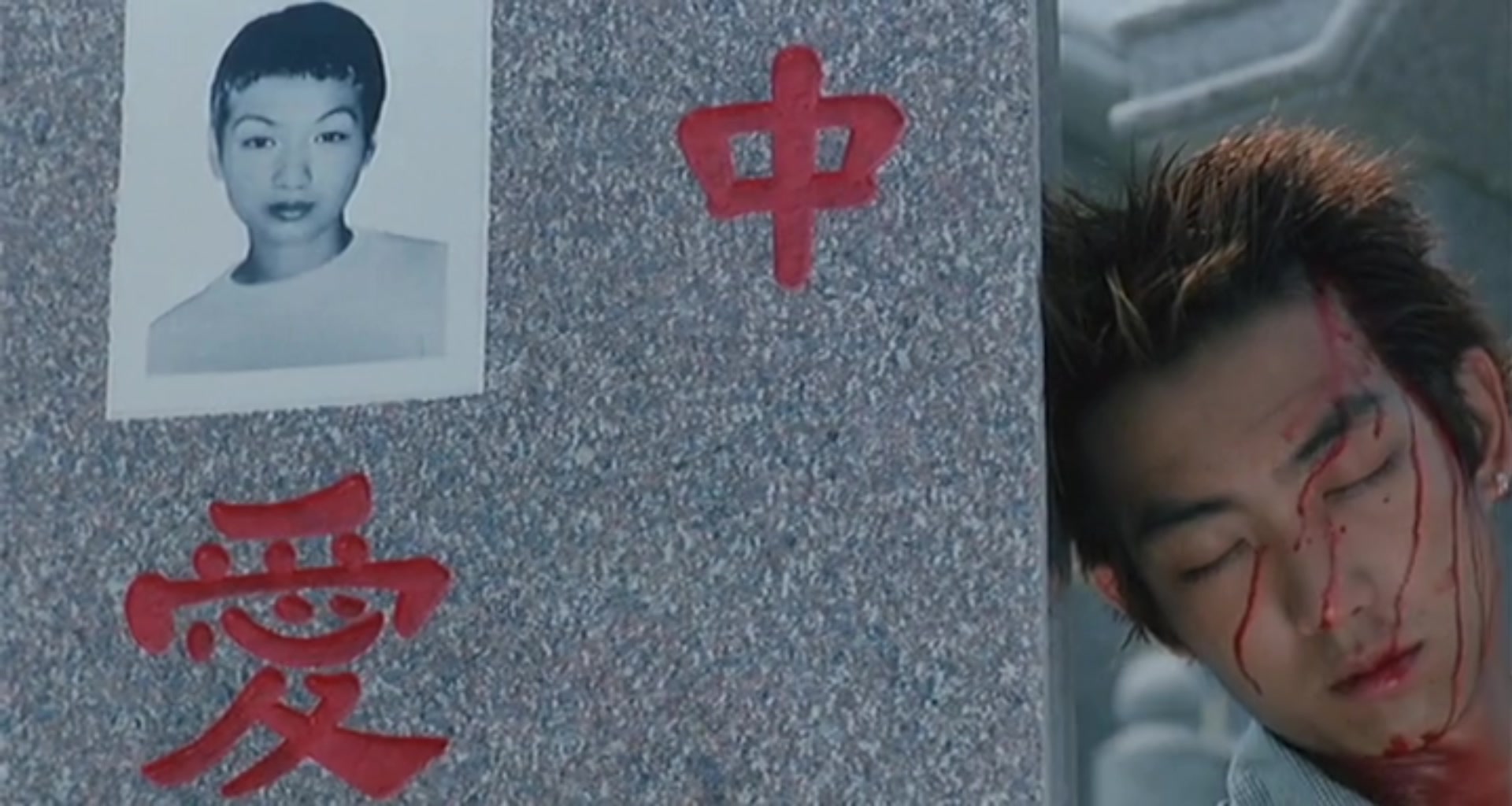

“The more I feel that 1997 is approaching, the more I think this group of teenagers did not think about the future at all, they have no way out.” Fruit Chan said, describing Autumn Moon, Ah-Lung and Ping. Starting with a girl Ah-Shan who died, Ah-Lung picked up her suicide notes. Since then, Moon often dreamed of Ah Shan with wet pants.

The themes are not mainly about the dark life of the village boys, or about the youth, sex, and death of young people around a few protagonists. It is an ideology of nihilism: “ Everyone has no way out.” Chan neatly shows the state of existence of 1997 Hong Kong people. It’s not pretentious and pie in the sky, it happens in the subway where he sits, in the crowded market where he buys vegetables, in all the ordinary people and things he sees in his cynical and exhausted eyes.

Film still from Made in Hong Kong

The death of the protagonists symbolizes our helpless state after the Handover. Moon tried his best to find his mom and save Ping and Lung, but destiny and the brutality of authority led him to death. In this chaotic and brutal society, the intuition of reckless passion leads us to a lethal death.

“但有一樣嘢我相信有嘅,就係我哋而家好開心

因為要面對一個未知道嘅世界,我地已經得到免疫。”

Eventually, the ghost of Moon was satisfied as the three of them had already got rid of the abyss of unertainty. “Thousand of words” inside their hearts, sink into soil, but no one understands. It is unnecessary to literally quote People’s Radio Hong Kong at the end but Chan did it. The death knell rings, the beauty of survival remains, amidst the dregs of humanity.

“世界是你們的

也是我們的

也歸根結底也是你們的

你們年輕人朝氣蓬勃

正在興旺時期

好像早晨八九點的太陽

希望寄托在你們身上

現在你收聽的是香港人民廣播電台

以上播送的是毛澤東同志對年輕代表的談話。”

Breaking Free of Reincarnation : Dionysian Reenactment

HOW TO TURN resentment and pain into a new form of trailblazing energy? Hongkongers have already figured it out. The Yau Ma Tei boat affair, with refugees and boat people , the failure of the Revolutionary Marxist League, the Tiananmen Square massacre, the Queen’s Pier demolition, the Umbrella movement …and the anti-ELAB movement. We try to tell the world about our striving, and the world we reconstruct based on the history of fighting against different regimes. 1,114km² of land became polished by trauma, washed with tears and sweat, finally aspiring too the stars. No matter who our enemy is, we aim for the fair treatment of our home, Hong Kong.

Losing Sight of A Longed Place aired at the Open University of Hong Kong Graduation Show on June 23, 2017, was shortlisted for the Golden Horse Awards on October 1, and won the best animation award on November 25. This short animation was inspired by a Romanian animation, The Magic Mountain, about the struggle of Polish anti-communist artist Adam Jacek Winkler. During the one-year production period, director Jess said they took the longest time to construct the story. They interviewed ten gay friends successively, and finally decided to record the experience of one of the interviewees, Yin Haowei.

In 7 minutes and 45 seconds, they used watercolor paintings and stop motion to bring the audience to recognize Wei from the perspective of family, society, and politics. Wei is the chairman of Action Q, a college LGBTQ activist group. He actively fights for gay rights in social movements, but he is not accepted by his father after ”coming out“.

From the subtle and raw illustration of how Wei ran out of his home, crying and falling over in despair, his warm kiss with his lover, and protest sites and camps at Tamar Park, the mild but heavy brushwork reflects Wei’s complex and vulnerable mental state. The walls, sky, and roads surrounding Wei are high and vague.

“Why does dad hate me and my boyfriend?” “Can Hong Kong still have democracy?”. Director Jess said “We did not expect to include the context of the Umbrella Movement. This is part of Wei’s life. During the interview with him, we realize he connects with politics and social issues passionately.” At the same time, he is trying to break through the dynamics of power and authority. Inequality has different layers and forms and this animation fully manifests the mental and external turmoil of some specific characters and groups.

Their daily lives are struggling but beautiful, creating and reinventing collective history at the same time. We can see Wei underwent relentless repetitions of despair, disappointment, resentment, and confusion, but he gave his life and society a novel interpretation: to strive for democracy with a queer identity.

Animation and painting highlight the abstract mental states of characters, as film and documentary reconstruct time and space. In 2022, Blue Island was released in Taiwan but not Hong Kong. The director of Yellowing (2016), Chan Tze Woon, uses reenactment as the prime narrative technique via the characters who experienced the 1967 riots, 8964, the 2014 Umbrella Movement, and the 2019 anti-ELAB movement to ask a question: “What is Hong Kong to you?”

Post for Blue Island

What the movie shows us is how the characters’ emotions, experiences, and despair are constructed, and what the correlations between individuals and factual history is. Chan makes the context of Hong Kong’s social mobilizations into an origin, giving it a definition and an identity that it may not have had for itself. We can see the shapeless continuity of Hong Kong’s chaotic past, but now it becomes a discrete and well-defined experience, for which only repetition and a new reading can provide a possible meaning.

In the film, reenactors are invited to express their thoughts, open up about their opinions, requiring the old generation of Hong Kong activists to engage in a reenactment. As an old activist watched the fiction of the Maoist ideology in Guangdong, he whispered ”It is not true.” The director does not treat “re-enactment” as a manipulation to make the audience believe that the re-enacted image is a kind of reality. It is a trailblazing way that creates a new space which is timeless, to enable different people in a different time and space to talk, understand, and respond to what is happening in a macro-spatial setting of the metropolis.

Curtain Call

LAYER-BY-LAYER, now we see more clearly how we came along over these fifty years. Getting out of the spectacle inside Plato’s cave, carrying this spirit, it is time to build our ideal world.