by Enbion Micah Aan

語言:

English /// 中文

Photo Credit: Gunda

GUNDA IS is the kind of documentary film that makes cinema art. The world Gunda created is imbued with mystery, love, and beauty. Master filmmaker Victor Kossakovsky is a courageous filmmaker with a firm belief in the power of sounds and images—the film has no dialogue or narration of any kind, and the entire experience consists of watching filmed reality with only diegetic sounds.

Unlike Kossakovksy’s last film Aquarela—a sweeping and ambitious project—Gunda is intimate and empathetic in a way that is never didactic. Gunda recalls some of the greatest masters of cinema: it has the quality of Frederick Wiseman’s “fly on the wall” documentary approach, Bela Tarr’s craftsmanship, Robert Bresson’s sophistication, and Chantal Akermans’ attention to the everyday.

Trailer for Gunda

By now, if you are a cinephile, after reading the above paragraph, you’d probably be excited to see Gunda with no more convincing from me. However, otherwise, you’d want to know what makes Gunda worthwhile other than the aforementioned stylistic and artistic similarities. I am a firm believer that great art should be approachable, but a “slow” film such as Gunda with no conventional narrative structure or characters can strike non-cinephiles as simply slow or boring. Though technically excellent, a film like Gunda does require some effort on the audience’s part. It is about the titular character, a mother sow on a farm, but it does not tell a story, and it makes the point of only showing but not telling to give the audience a purely visual and auditory experience. In other words, Kossakovsky is placing his trust on the audience here to watch the film mindfully—this is perhaps the ultimate respect a director can give an audience.

I would like to urge anyone who recognizes that cinema has the potential to be art to go see Gunda in the theater and rather than a description of the film, per se, instead, offer a sort of a “guide” as to how to watch such a film. Instead of looking for the “effects” or “stories” that we are so accustomed to seeing, simply relax and look closely with intent to see what the images and sounds are describing. Look at how the piglets walk, pay attention to the mother sow’s expression, and how the feathery steps of the chickens can carry so much weight. Pay attention to normally mundane sounds of the farm, such as cars passing by and, of course, the sounds of the mother sow and piglets.

It is not a particularly demanding task to appreciate such a film, but it does require the audience to let go of expectations of a conventional film. If you are able to simply sit down and be present with the images and sounds, you will be able to immerse yourself in the world of Gunda and be rewarded and enchanted by its simplicity and beauty.

The artistry of Gunda can easily be overlooked because it is rather subtle—everything is filmed masterfully, and the sound design is not only subtle but highly effective. Images work and describe a scene well because the mistakes are not present—all the difficult technical issues are resolved beforehand, so in a film with many long takes, without a conventional story structure, it can be easy for the audience to take masterful cinematography for granted. Again, here, I urge anyone going to the theater to see the film to simply be present with what is in front of you.

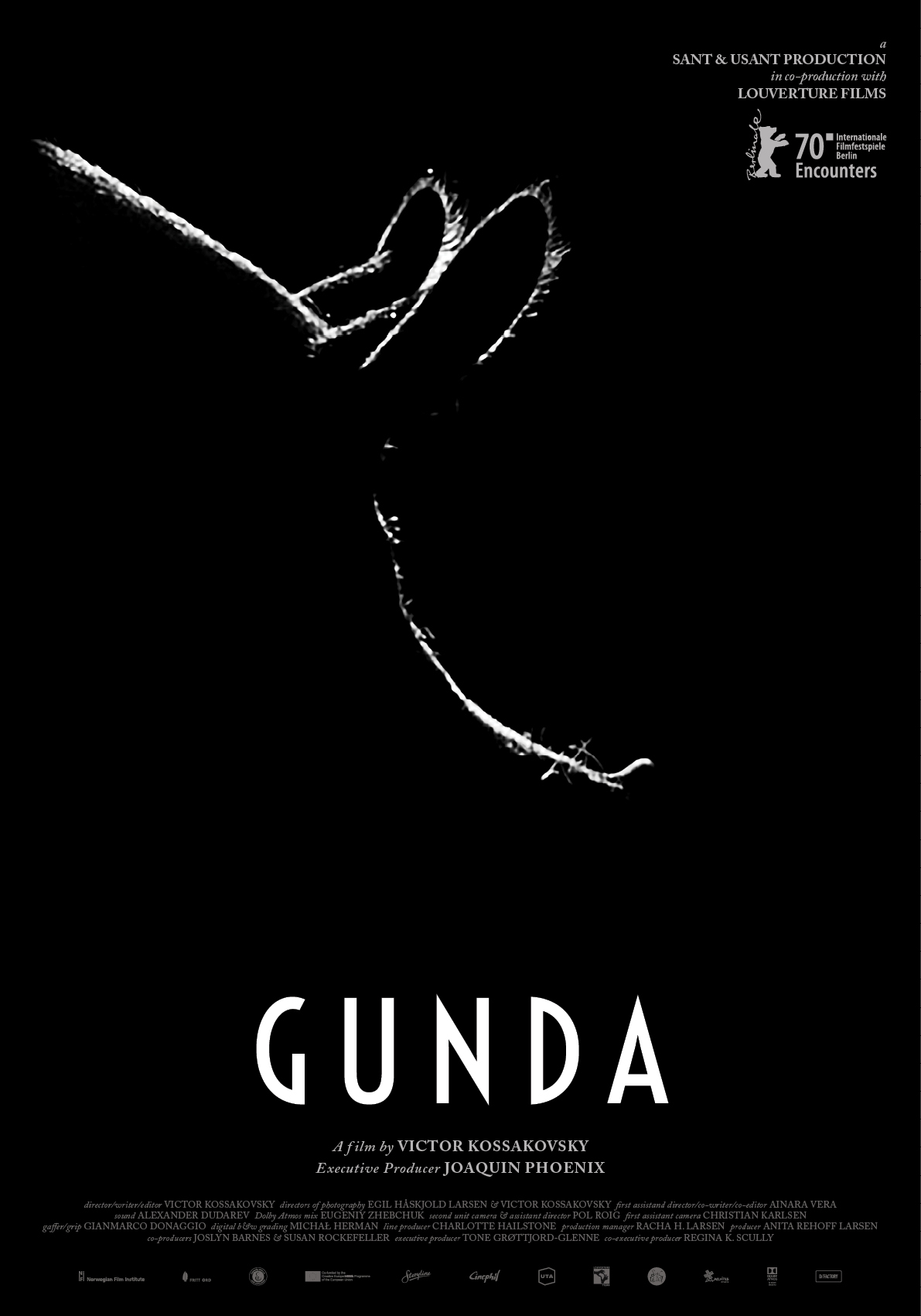

From the marketing material I have seen in Taiwan, it is evident that the film’s distributor has little faith in the marketability of the film—after all it is a black and white documentary with many long takes. The poster and postcards have different release dates, and the image on the poster looks pixelated because of issues of low resolution. Since the image used in the poster is only the highlight of a pig, this is an easily fixable problem even if one does not have the picture in its correct resolution. But, apparently, the distributor in Taiwan had so little faith in the film that a pixelated poster is not a thing worth fixing.

Film still. Photo credit: Gunda

This is not to mention the marketing department’s emphasis is on the film’s nomination in the Oscars, an award cinephiles generally do not care that much about—as film critic Luke Buckmaster correctly pointed out: “Gunda was shortlisted for the Oscars but would never have made the final cut. An outfit like the Academy Awards can’t recognise the brilliance of this film.” It is rather sad that the marketing of a masterful film is handled so poorly—it is as if the distributor has no idea why Gunda is a great film and expresses their disdain for the film in its marketing.

Normally, a film like Gunda would only be available to film festival audiences, so it is quite an opportunity to be able to see the film in a conventional movie setting. Possibly because the film is attached to Joaquin Phoenix, who executive produced it, the film was able to be released on a worldwide scale. The theater I went to was only showing the film twice a day on its first weekend, so anyone who is interested should try to make the point of going to the theater soon to watch it, as it is likely that the film will not be available for long and it is even more unlikely that this film will be available on the big screen in the future.