by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

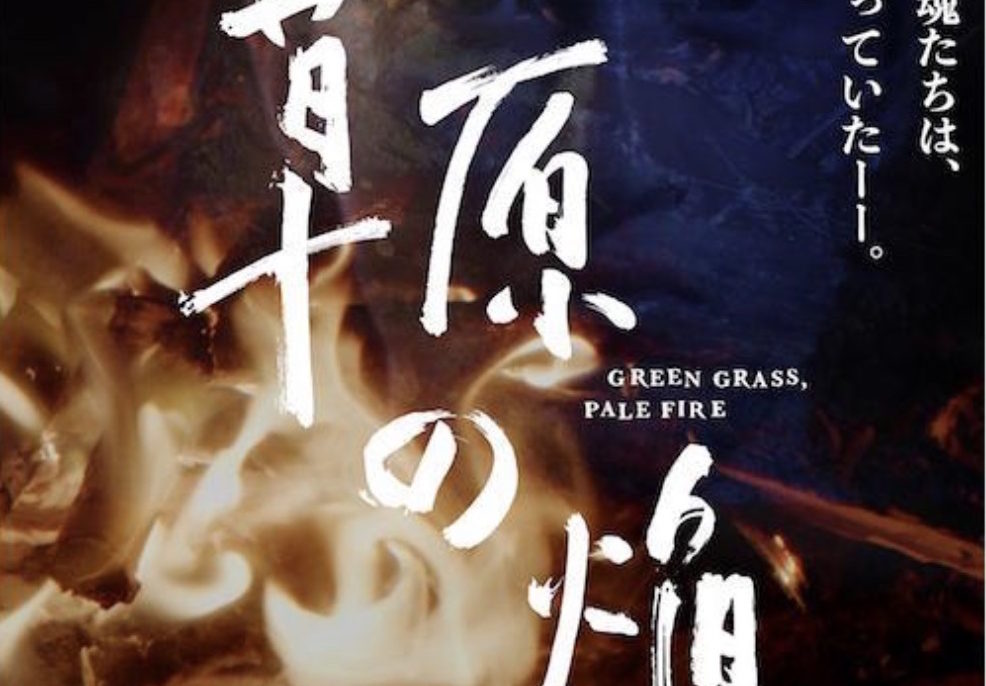

Photo Credit: Film Poster

This is a No Man is an Island film review written in collaboration with Cinema Escapist. Keep an eye out for more!

GREEN GRASS, Pale Fire (草地火焰) follows three Taiwanese runaway miners in 1935 who are on the run from the Japanese army. Stranded in the jungles of Iriomote Island, Okinawa prefecture, after having escaped from the infamous “Green Jail” coal mine, the three hope to find a way home by boat. Given this setting, the short film explores Taiwan’s Japanese colonial period, which lasted from 1895 to 1945.

While sitting around a campfire playing cards, they find themselves under assault from a mysterious intruder. It is here that the story takes a turn for the apparent supernatural, with the suggestion that the runaway miners are ghosts, caught in an endless cycle of killing each other, and unable to find their way home.

There has been renewed attention to the “Green Jail” coal mine as of late, as also observed in the release of a documentary by the same name. Green Grass, Pale Fire shares the same director and production crew as the Green Jail (綠色牢籠) documentary. Some scenes from the film are also used in Green Jail. The film can be seen as the semi-fictive corollary to the Green Jail documentary, then.

However, more generally, there has long been a rich vein of Taiwanese depictions of the Pacific War that focus on Taiwanese escapees from the Japanese army, such as Li Qiao’s The Solitary Light, the concluding book to his famous Wintry Night trilogy. This is to be contrasted with the historical fact that some of the last holdouts of the Japanese Imperial Army after World War II were, in fact, Taiwanese. The film may mean to evoke this past.

Green Grass, Pale Fire is sparse in dialogue and characterization. The film, which claims to be a “reenactment,” is not a period recreation of the 1930s. Its protagonists look too clean-cut and modern—not at all like former miners. A skeleton that appears in a surreal moment from the film looks like a toy, rather than an actual skeleton, and a scene involving a character bleeding to death from a wound is not portrayed realistically.

Green Grass, Pale Fire is not meant as a realist depiction of history—and it more makes up for this with its atmospheric setting and vivid imagery. The film skillfully conjures an atmosphere of dread as the film goes on, though the action remains confined to the campfire the three protagonists are around.

The cinematography deliberately limits the elements present in the film. The majority of the film’s action takes place around a single campfire, there are only three characters, , and only a few props, such as with a knife or a glass bottle, feature in the film. In this sense, the movie is minimalist.

However, the film plays with the elements it introduces by rearranging them, and playing with perspective. This is what establishes the sense of “haunting” present throughout the film, as well as the suggestion that its protagonists are caught in an endless loop. In this sense, Green Grass, Pale Fire is not a narrative work, per se, but reminds more of video art.

Thematically, Green Grass, Pale Fire is not especially original, in that many depictions of the Pacific War from Taiwan or elsewhere have centered around this theme of haunting—particularly regarding the “nameless” soldiers that disappeared into the jungle during it, never to return to their homelands. In this respect, the aesthetics of Green Grass, Pale Fire are also not original but rely on genre tropes, drawing on muted jungle tones to convey a sense of the supernatural, and showing a ghostly photograph of its protagonists during the end credits.

In this sense, the film is best seen as a stylized “re-staging” of history, highlighting the lingering specters of a neglected part of Taiwanese history, rather than an attempt to conventionally dramatize that period, or to make any great stylistic innovations. Consequently, it is probably deliberate that Green Grass, Pale Fire begins as though it is a realistic, mimetic depiction of history, before the turn toward the introduction of supernatural elements.

This is to be contrasted with other recent Taiwanese documentaries that tend toward wholesale experimentalism, such as Le Moulin—which won best documentary at the Golden Horse Awards in 2016 for its depiction of the Japanese colonial period, but views more like video art than documentary. Yet if one sees Green Grass, Pale Fire and Green Jail not merely as complementary works, but as two works as comprising a whole, it can be understood as part of these same trends in Taiwanese documentary.

Green Grass, Pale Fire is evocative and it skillfully conjures ambiance. It may add very little to one’s knowledge of the period, but in taking known history and “de-constructing” it through the use of supernatural elements, it rather serves as an aesthetic intervention into Taiwan’s past. The film may be one that individuals interested in Taiwanese history enjoy, but it may remain opaque for others.