by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: A First Farewell

This is the first in a series of upcoming No Man is an Island film reviews written in collaboration with Cinema Escapist. Keep an eye out for more!

A FIRST FAREWELL (第一次的離別) is a remarkable film by first-time director Wang Lina (王麗娜). The film is shot in Wang’s hometown of Shaya, Wang being a Han director that grew up in Xinjiang.

As a film shot in Xinjiang under the present political climate and one which Chinese authorities have allowed to be distributed internationally, that the film exists at all is remarkable. Indeed, if not for the cooperation of companies close to the Chinese government, such as the state-owned Emei Film Group and Tencent’s cinema arm, Tencent Pictures Cultural Media, it is probable that the film would not be able to be made. However, even just in terms of formal qualities, the film is a standout.

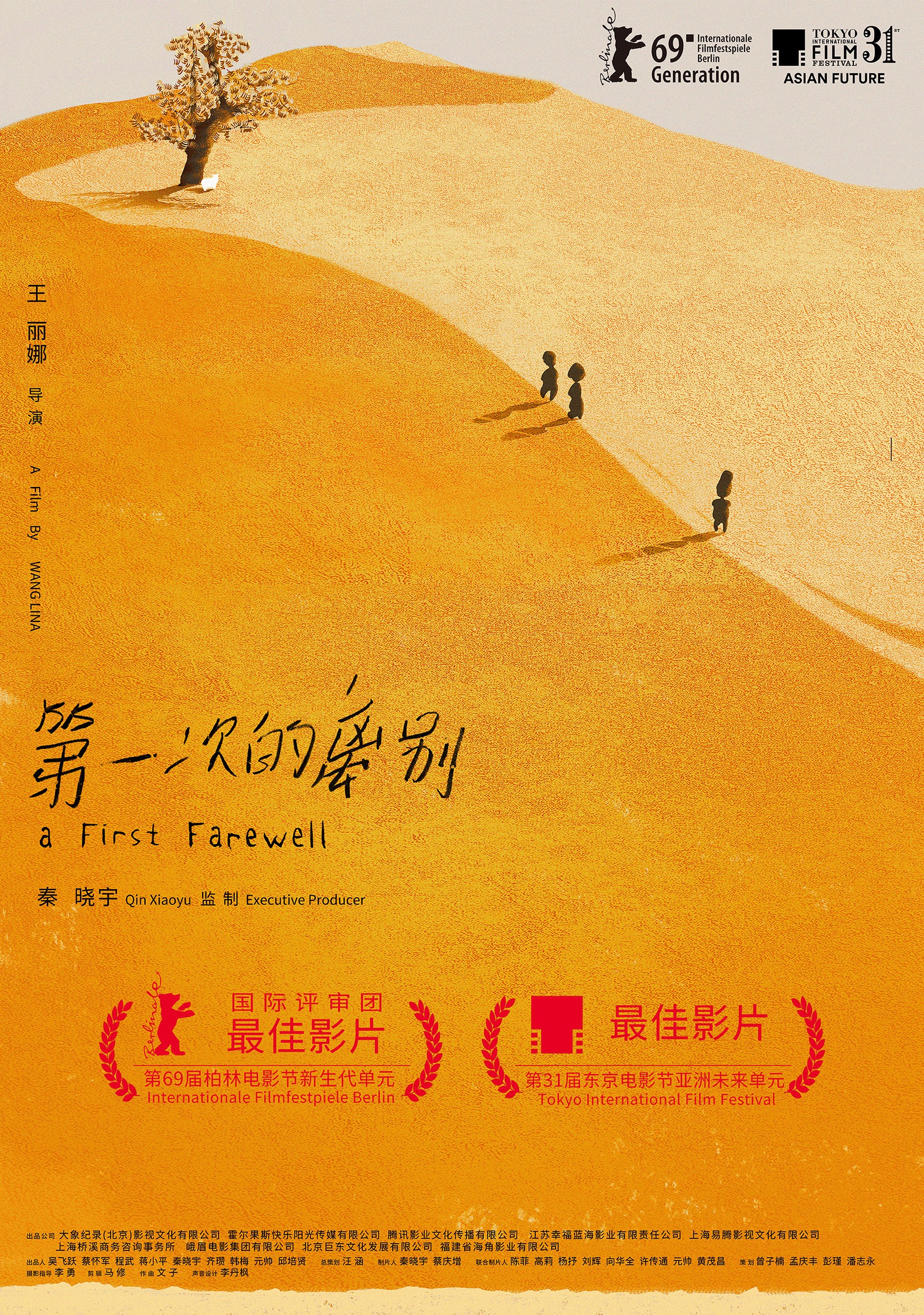

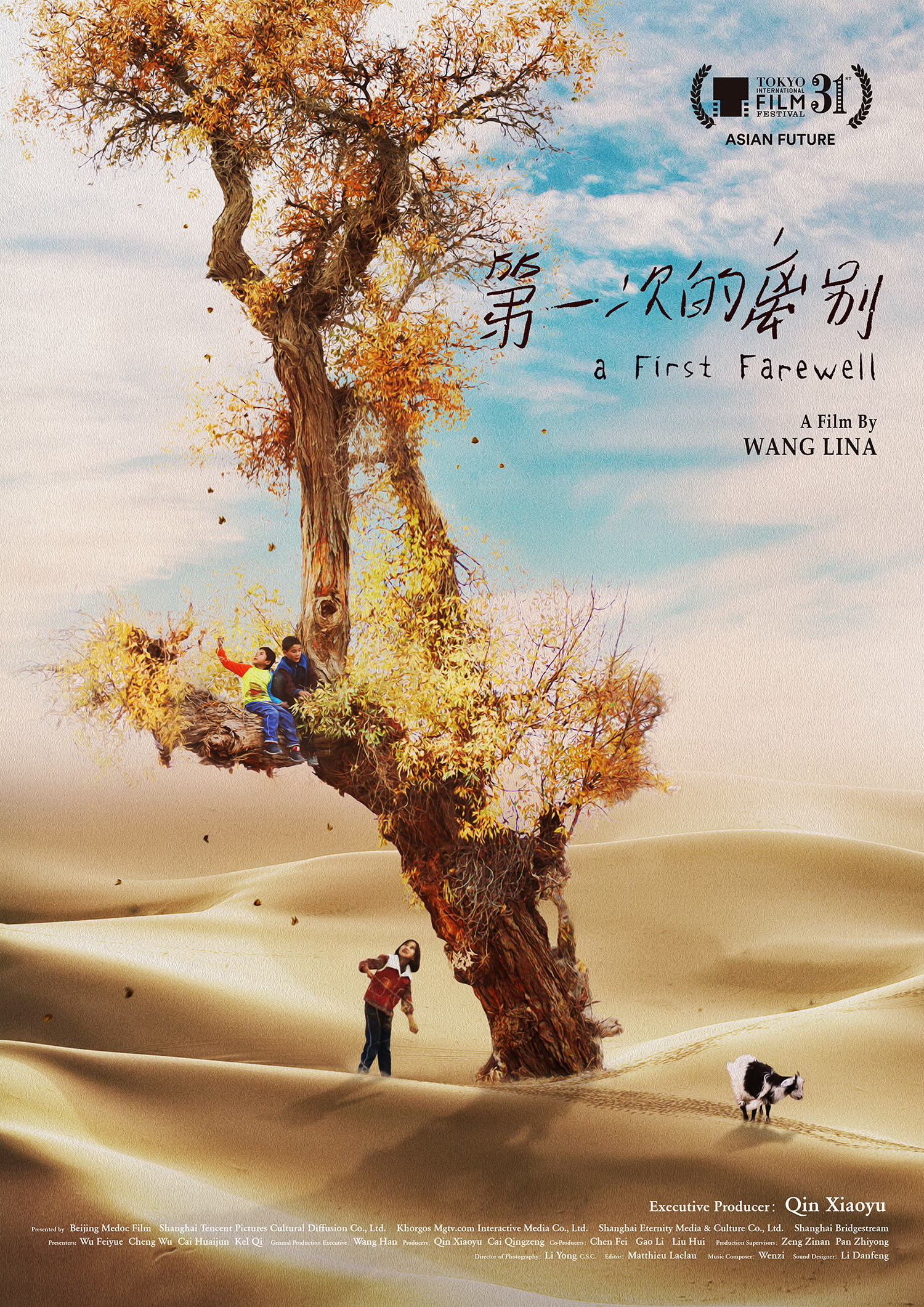

Promotional image for A First Farewell. Photo credit: A First Farewell

A First Farewell focuses on a group of three Uighur children. The film begins by depicting Isa, a young Uighur boy, and his relationship with his deaf-mute mother. Plans by Isa’s father to send his mother to a nursing home are among the first of the farewells that the film’schild protagonists experience. Other farewells subsequently ensue due to plans by Isa’s older brother, Musa, to travel to the city to experience the world beyond the countryside, and plans by his friend Kalbinur’s parents to send her to Mandarin-language school in order to afford her the greater opportunities that Mandarin fluency brings.

More broadly, then, the film suggests that Uighurs in rural Xinjiang confront conditions of uneven development, something that results in many partings. This is probably the interpretation of the film that made it amenable to authorities–after all, despite that estimates currently suggest that over one million Uighurs are imprisoned in “reeducation” camps in Xinjiang, the Chinese government claims that it is only seeking to encourage development in Xinjiang. This interpretation of the film that lends itself to official narratives that would see the film as a realist depiction of social conditions in Xinjiang–the film has been praised by propagandistic Chinese state-run media outlets such as the Global Times and China Daily.

At the same time, it is not hard to pry subversive readings from the film. The institutionalization of Isa’s mother in a nursing home is very easily read as a metaphor for government internment. During a family discussion about what is to be done with Isa’s mother, one of Isa’s family members comments, “the government is our father.” This is seemingly juxtaposed with scenes of the children protagonists swearing loyalty to the government during school ceremonies that come shortly after. Scenes of farm animals also implicitly raise the metaphor of the Uighur characters as livestock.

That being said, the debate over whether a Chinese film is “subversive” or not often misses the point, when such relations are better understood as constantly negotiated. One notes that in the early 2000s, the films of Zhang Yimou were perceived as subversive when distributed on the international film festival circuit, with films such as Not One Less interpreted as a form of social critique–a film with strong parallels to A First Farewell, because of its use of child actors and focus on conditions of uneven development in rural areas in China–and as having only introduced vaguely propagandistic plot elements to avoid censorship. Later on, more overtly nationalistic elements crept into Zhang’s films, as seen in Hero or The Great Wall, causing a sense of betrayal from those who had previously been praiseworthy of Zhang.

Apart from stellar acting by the child actors in the film, A First Farewell is beautifully shot. Each scene evokes the beauty of forests and desert in Xinjiang while avoiding exoticization, and maintaining a sense of naturalism. To this extent, it is worth noting that A First Farewell strongly evidences the aesthetics of sixth-generation Chinese film, particularly in the way that it blends the documentary and fiction genres. Wang shaped the film around the real-life circumstances of the child actors. For example, the child actor who plays Isa, who is, in fact, named Isa, does actually have a deaf-mute mother. According to an interview with the Global Times, Wang stated that sometimes she set up scenes to evoke the emotional responses of the child actors in the film, such as filming their real responses when late for school.

Film poster for A First Farewell. Photo credit: A First Farewell

A First Farewell can otherwise be categorized as “ethnic minority film,” in the sense that the film is the latest entry in the long history of film about China’s “ethnic minorities”, invariably filmed by a Han director. Ethnic minority film has historically drawn from the dominant aesthetics of Chinese film at the time and A First Farewell’s sixth-generation stylings can be understood in this vein. But, to this extent, even early ethnic minority films shot as part of early Chinese socialist realist film blended fact and fiction–many of the actors in 1963’s Nongnu, shot in Tibet and often considered a masterpiece of Chinese ethnic minority film, did not only play slaves but had, in fact, been former slaves.

A First Farewell can perhaps be productively understood within the frame of Chinese ethnic minority film, then, something complicating questions of representation, complicity, and subversiveness. However, apart from the rare glimpse into Xinjiang that the film presents, it is one worth watching just in its own right.