by Enbion Micah Aan

語言:

English /// 中文

Photo Credit: Enbion Micah Aan

I’D LIKE TO start this review with a disclaimer that though I try to be as objective as possible in my evaluation of Chen Cheng-Hsiung’s work (please do not confuse him with the painter who has the same name), I might be biased. I have personal connections to Chen Cheng-Hsiung. Tainan, where I am from; being a small city, it should not surprise. Anyway, Chen’s son went to high school with my brother, and his wife is my mom’s friend. The last time I met Chen, it was at a dinner function many years ago. My impression of him was that he was quiet and reserved, and like his work, one can sense the inner strength that guides him. You may not have heard of Chen, but in the art community in Tainan, he is one of the rare figures whose work and work ethic is admired by just about everyone.

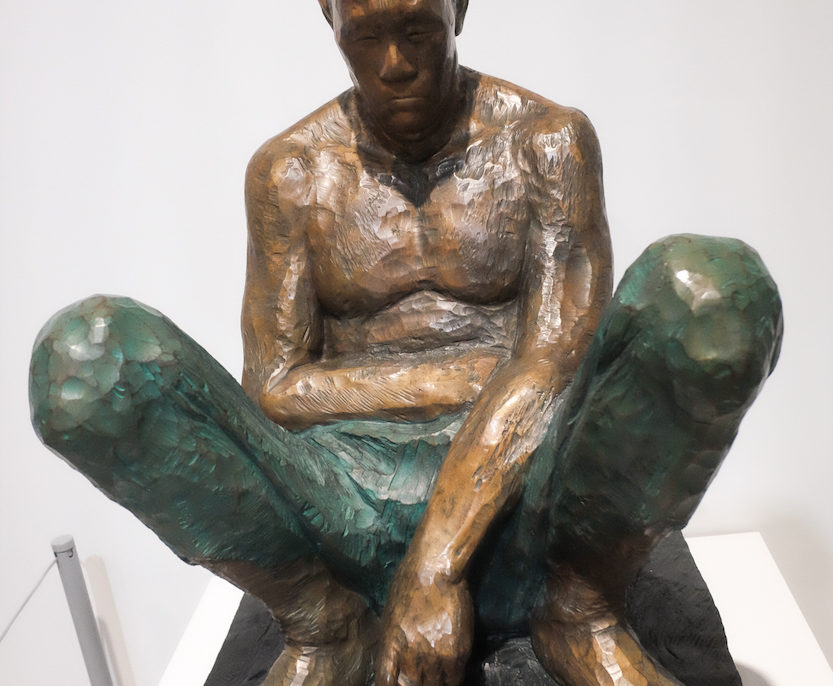

Tainan Art Museum has some of his most well-known works on display in the preliminary exhibition. These pieces are from his mature period and are very fine examples of his work. As a young man, Chen learned his craft as an apprentice to a master sculptor of religious figures. Chen started his sculpture career as a craftsman for religious sculptures, but as he matured as an artist, his interest started to change and he started to focus on ordinary people—oftentimes laborers and other working people, as his subjects. By doing so, he’s able to, artistically speaking, elevate ordinary Taiwanese people’s dignity and everyday life to the status typically only reserved for gods, goddesses, and people in high places. As such, Chen’s work shares some parallels with social realists, but the similarity stops at the subject. What concerns Chen is the dignity and feel of ordinary Taiwanese people’s everyday existence, as opposed to social forces and class struggle.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Chen’s sculptures of “ordinary people” are anything but ordinary. They are certainly much quieter than most sculptures we would expect to see in museums. Chen does not care for overt formalism that emphasizes geometry and abstraction, like his contemporary Ju Ming (朱銘). And unlike his other contemporary Wu Ching (吳卿) who, in his women’s underwear sculpture, meticulously shaved wood down to the point that it is almost see-through, Chen is not trying to show off his sculptural prowess with his work. However, this is not to say that Chen’s work does not have great formal qualities or Chen’s work requires less skills than Wu. What makes his sculptures extraordinary rests precisely on the fact that the formal properties of his work do not draw attention to themselves, and the artist’s skills serve to elevate the subjects as opposed to be a testament to the artist’s technical prowess.

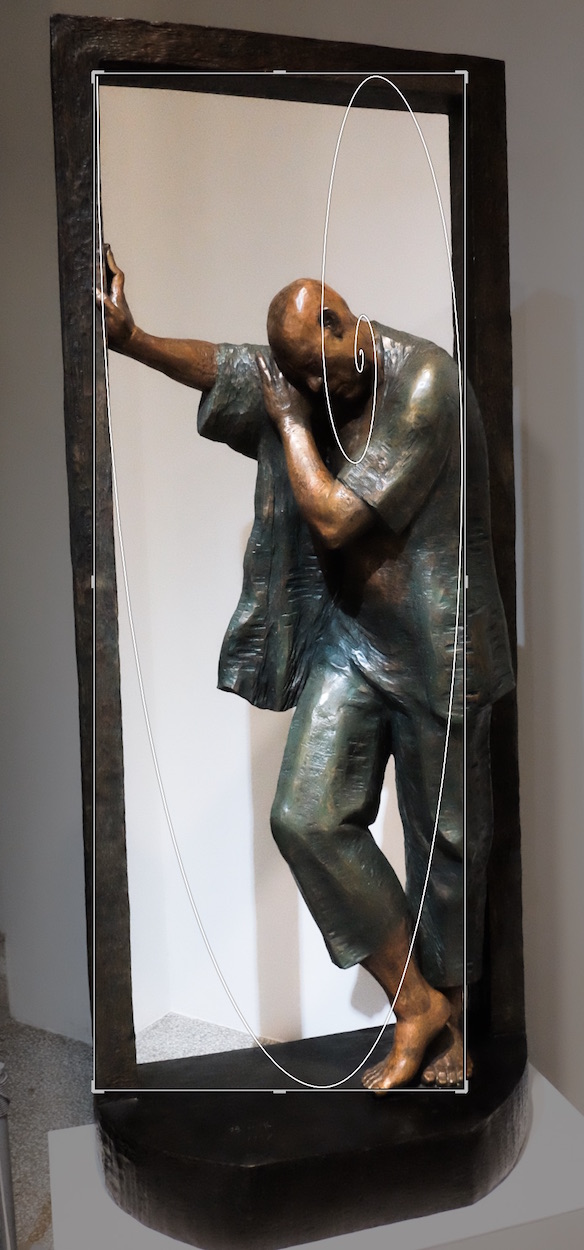

The first piece the visitor sees is a piece from “The Dream of the Fishermen” (討海人的夢) series—a man standing at the doorway. Perhaps half asleep, the man stretches his right hand up to the door frame, resting. Looking at the sculpture straight on, the man’s posture evokes the theme of dreaming, as the man, with his eyes closed, looks as if he could be asleep. However, upon closer examination, the expression suggests a much more complicated psychological state—the man looks contemplative and his tense yet unexaggerated expression reminds the viewer of our deep concerns for daily struggle. That he is at the doorway also suggests that he is at a crossroad, perhaps facing a great dilemma of making a life decision.

Golden ratio superimposed upon Chen’s sculpture. Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Now let us step back and look at the sculpture from afar and analyze its form, since without Chen’s masterful composition, the sculpture would not be able to evoke such a complicated narrative and emotional state. For viewers paying close attention to the formal quality of the sculpture, the first thing that would jump out, is that the door frame and the figure is the most classic of classic compositions, the golden ratio. The advantage of using such a classic composition is that the visual balance is achieved without losing any of the dynamic movements. Now pay attention to the head that is a circle, the elbow and the knee that form triangles, how a line forms between the left upper arm and the knee, a triangle that a tip-toe foot forms, and many other geometry elements. The golden ratio and complicated geometrical composition here is something that even the most minimalist sculptors, whose only objective is to create perfect compositions, without all the nuanced narrative seen in Chen’s sculpture, would envy.

Now let us get closer to the sculpture still and look a bit more closely at details. One of the characteristics of Chen’s style is that he leaves sculpting marks on the sculptures. This sculpture is a copper cast, and I believe this was originally done as a wood sculpture and later cast as copper. It is not difficult to leave carving marks on wood sculptures—all one needs to do is not polish it. However, what is difficult is that Chen leaves the marks on his sculptures, much like master painters use brush strokes, and yet the marks do not distract the subject or work against the sculpture. In fact, the marks Chen leaves on his work enhances his subject. The carving marks are there, but so are the creases on the shirts and pants, along with the wrinkles on the man’s face. The clothes are as flowy as actual pants and shirts, and the bone structure and muscles of the man’s leg and shoulder can even be seen through the clothes.

Photo credit: Enbion Micah Aan

Obviously, this is not the only work that is worth a closer look. All of the sculptures in this exhibition deserve close attention and appreciation. Chen is an artist who excels at expressing beauty while portraying ordinary life. Through everyday scenes, the other sculptures explore themes of friendship, joy, the relationship between a son and an elderly mother, and the concentration of musicians playing instruments. Though only a preliminary exhibition, there is more than enough art in this exhibition for viewers to see the extraordinary in ordinary life.