by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

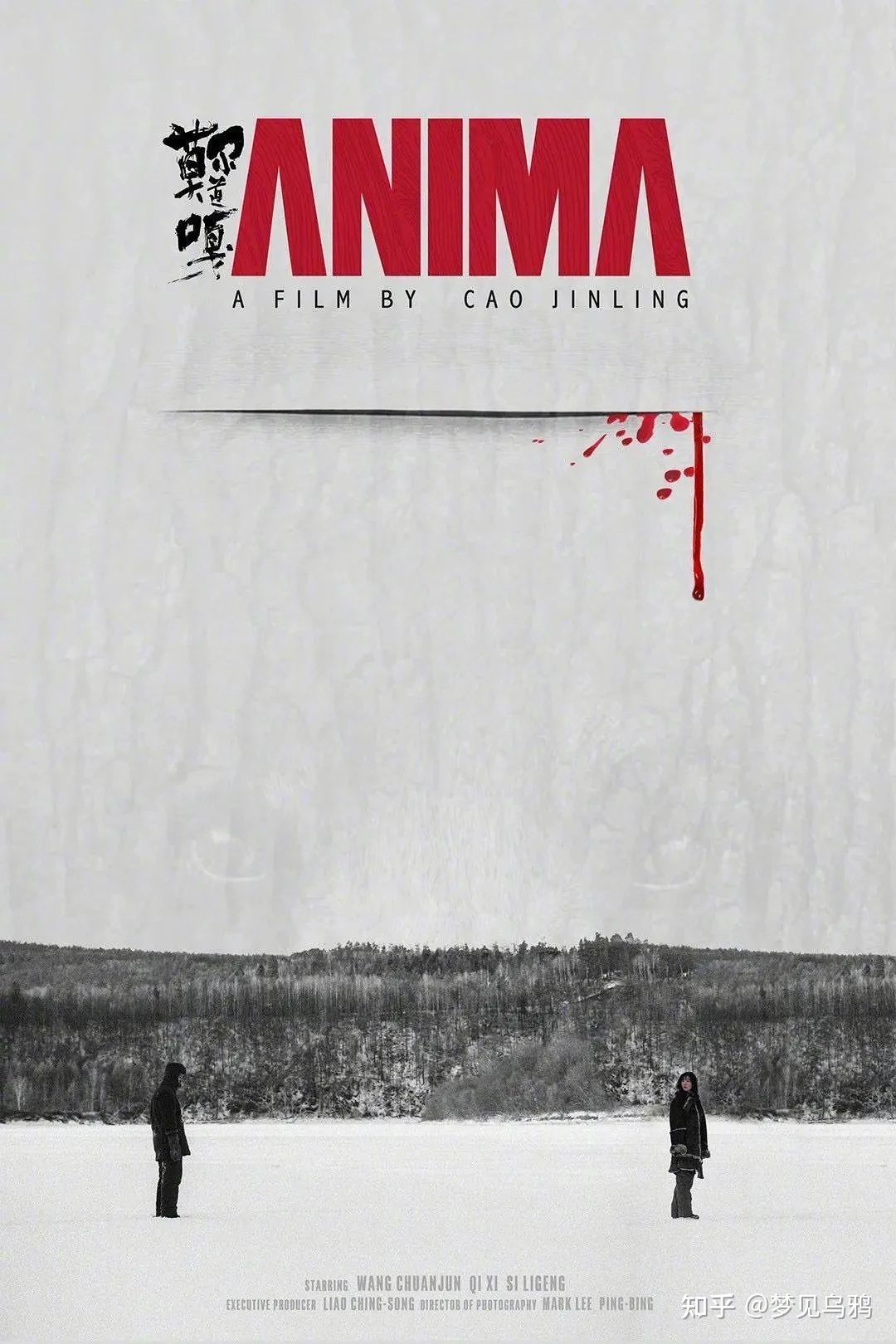

Photo Credit: Anima

This is a No Man is an Island film review written in collaboration with Cinema Escapist. Keep an eye out for more!

ANIMA (莫爾道嘎) DEPICTS the human effects of unfettered development in China, while also featuring elements of Chinese ethnic minority film. The final results are passable and the film’s technical merits are impressive, but the work does not break new ground.

Set during the 1980s in inner China, Anima follows two brothers, Linzi and Tutu. The two are raised in an Evenki family, though Linzi is a Han orphan adopted by the family—the Evenki are one of China’s 56 recognized ethnic minorities and have a population of just over 30,000. Contextual clues suggest that, like many Evenki, the family are believers in Tibetan Buddhism.

When the brothers are children, Linzi and Tutu’s mother suffers a tragic death. When a bear attacks, Tutu shoots and kills it—but accidentally hits his mother in the process as well. As killing a bear is considered taboo in Evenki society, Tutu comes to believe that he is cursed.

Both brothers grow up to become loggers working for a government work team. However, they come into conflict. Tutu wishes to make more money by illegally smuggling lumber, while Linzi is focused on preserving the forest areas that they have grown up in. The relationship between the two brothers ultimately reaches a breaking point when the two fall for the same woman, Chun, who Linzi encounters while she’s hunting for bears to avenge her former husband’s death by bear attack. Linzi ultimately marries Chun, causing Tutu to drift away after several fights.

Years later, Linzi has a daughter and Tutu eventually returns to reconcile with both Chun and Linzi. But issues regarding overlogging in the area have gotten worse. Such matters come to a head when Tutu is arrested for smuggling, and the forestry team that Linzi works for discovers a grove of ancient trees that Linzi has been protecting.

Film poster. Photo credit: Anima

Anima shifts between several registers. As with other ethnic minority films of its kind helmed by a Han director, the film injects strong “ethnic” elements into what is otherwise a relatively realistic narrative, depicting several Evenki traditional rites when the two brothers are young. The film’s characters notably speak in Mandarin throughout, catering to an intended Han audience. Presumably Linzi is a made a Han character to provide these majority-Han viewers an entry point into the film; his Han background never really comes up in the film otherwise, and Linzi seems to think of himself as simply being Evenki. On the other hand, Tutu seems to be something of an ethnic minority film stock character of a rough and violent young man unable to control his passions.

The film manages several impressive set pieces, including a scene in which a tree tumbles onto Linzi and another logger, and a climactic landslide that occurs at the end of the movie. Anima was shot on location in Inner Mongolia’s Moerdaoga National Forest, and its camera seeks to intentionally draw out the setting’s natural beauty.

This, too, is in line with how Chinese ethnic minority films frequently spotlight the natural beauty of the environments that ethnic minorities live in, as if to suggest that they are intrinsically closer to nature than their Han counterparts. Indeed, Linzi—whose given name means “forest”—is depicted as having an almost spiritual connection to the forest. By the time the film ends, Linzi says he can hear the sound of the forest growing.

However, in this respect, the film is not very visually inventive regarding its depiction of natural beauty. This differs from the rich visual language developed by earlier films covering similar subject matter, such as “Fifth Generation” filmmaker Tian Zhuangzhuang’s films about ethnic minorities.

Indeed, Anima seems to owe something to the legacy of Tian and other Fifth Generation filmmakers, who were also Han directors that shot movies about ethnic minority subjects. Such movies were, in themselves, problematic. Yet Anima seems less original, less daring, and more commercialized of these earlier works

Still, Anima is an impressive debut for writer and director Cao Jinling. Though the film may not be terribly original for Chinese ethnic minority cinema, it is at least a cut above the ordinary by blockbuster standards.