by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

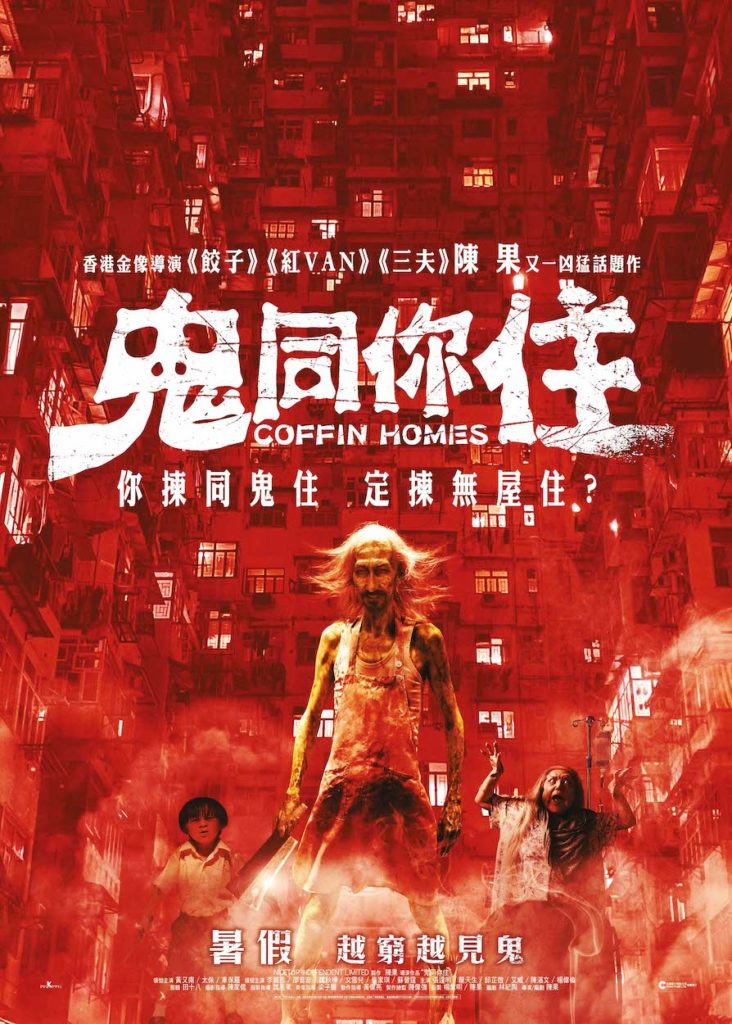

Photo Credit: Coffin Homes

FRUIT CHAN’S Coffin Homes (鬼同你住) is unlikely to find success on the international film festival circuit. For one, the film is likely to be billed as a comedy horror, though it is more accurate to locate the film in the mo lei tau style of Hong Kong slapstick.

However, the film may precisely be the sort of biting comedic satire that Hong Kong needs at a time in which Hong Kong film will probably become increasingly sanitized, out of political concerns. And Coffin Homes does not shy away from its subject matter.

Coffin Homes is sometimes described as something of an anthology film, which is true insofar as it focuses on a number of intersecting storylines. One follows a young real estate agent attempting to sell a “ghost home” in which a murder previously occurred to unsuspecting superstitious clients. Another follows the manager of a subdivided “coffin home” in which ten tenants have been crammed into what was previously one apartment. A third story, which opens the film but is given the least extra time, follows a rich family fighting over their future inheritance whose matriarch suddenly dies and becomes a zombie.

Trailer for Coffin Homes

Nevertheless, what proves truly subversive about the film is Fruit Chan’s depiction of Hong Kong. As Chan would have it, Hong Kong proves something like a capitalist purgatory in which not even the dead are safe, in which even the dead find themselves fighting for space in increasingly cramped apartment blocks with the living and are still bargaining and haggling to try and get the best deal. This proves a dog-eat-dog world for all involved, with the living having to be tricked about purchasing “ghost homes” or “coffin homes” and the dead unwilling to vacate these premises after dying miserable deaths in them.

In this respect, the cosmology of Coffin Homes almost proves something like a world without life or death. After death, there is simply more death—that is to say, the capitalist exploitation does not stop. This comes to the fore in a climactic, gory, and utterly hilarious fight scene between a number of ghosts in which characters continually kill each other and resurrect.

Nor does Chan shy away from political commentary. Hong Kong has traditionally been a regional financial hub, not only due to its international connections but due to its much-vaunted rule of law. Yet in a time in which Hong Kong’s political freedoms have increasingly deteriorated as a result of Chinese influence, Chan has no idealized romanticism for the past either.

In a surprisingly powerful moment, the film’s real estate agent protagonist, Jimmy Lam, goes through the various types of “coffin home” analogs that have existed in Hong Kong through the generations. Rather, as Chan depicts Hong Kong in his film, Hong Kong’s rule of law has always been characterized by its malleability. And to be a Hongkonger is to be willing to kill, undermine, trick, and exploit others.

In this respect, Chan is perhaps to be praised regarding spotlighting several southeast Asian characters, some of which are lifelong Hongkongers and other of which are temporary migrants. At the same time, perhaps the film falls into stereotypes, depicting Southeast Asian characters as having preternatural knowledge of the supernatural.

The film’s characters are more caricature than not, but You-Nam Wong’s Jimmy Lam is well-acted. Wong does an excellent job with physical comedy, particularly where the character’s facial expressions are concerned.

Film poster for Coffin Homes

Not all of the film’s plot threads fit together, with the third plot thread regarding the wealthy family fighting over their inheritance being the least developed thread. Chan begins with this family and aims to show the corrosive effects of greed on all levels of society, but it is also clear that he is more interested in the film’s working-class characters.

Given its subject matter, regarding poverty and unaffordable housing, the film is likely to raise some comparisons to Parasite, or perhaps even a supernatural horror version of Tsai Ming-liang’s Vive L’amour. Similar to Parasite, the film’s third act drags on a bit, with the film having any number of points in which the film could seemingly end but instead plodding on.

But Coffin Homes proves a strong entry for Hong Kong fictional film, with award-winning Hong Kong films more often being protest documentaries these days, and mo lei tau comedies likely to stick to increasingly safe topics going forward. In this sense, Coffin Homes is definitely worth a watch.