by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Brian Hioe

THE SU BENG MEMORIAL MUSEUM is small, occupying the two-floor apartment in Xinzhuang that Su Beng lived in at the time of his death in 2019. The museum may not offer any new insights for those familiar with Su’s life, but the history it displays is still revealing.

Su Beng, considered one of the significant founding figures of Taiwanese independence, is best known for his four-volume magnum opus, Taiwan’s Four Hundred Year History. Born during the Japanese colonial period as Shih Chao-hui and having converted to left-wing political views while studying abroad in Japan, Su traveled to China to act as a spy for the CCP.

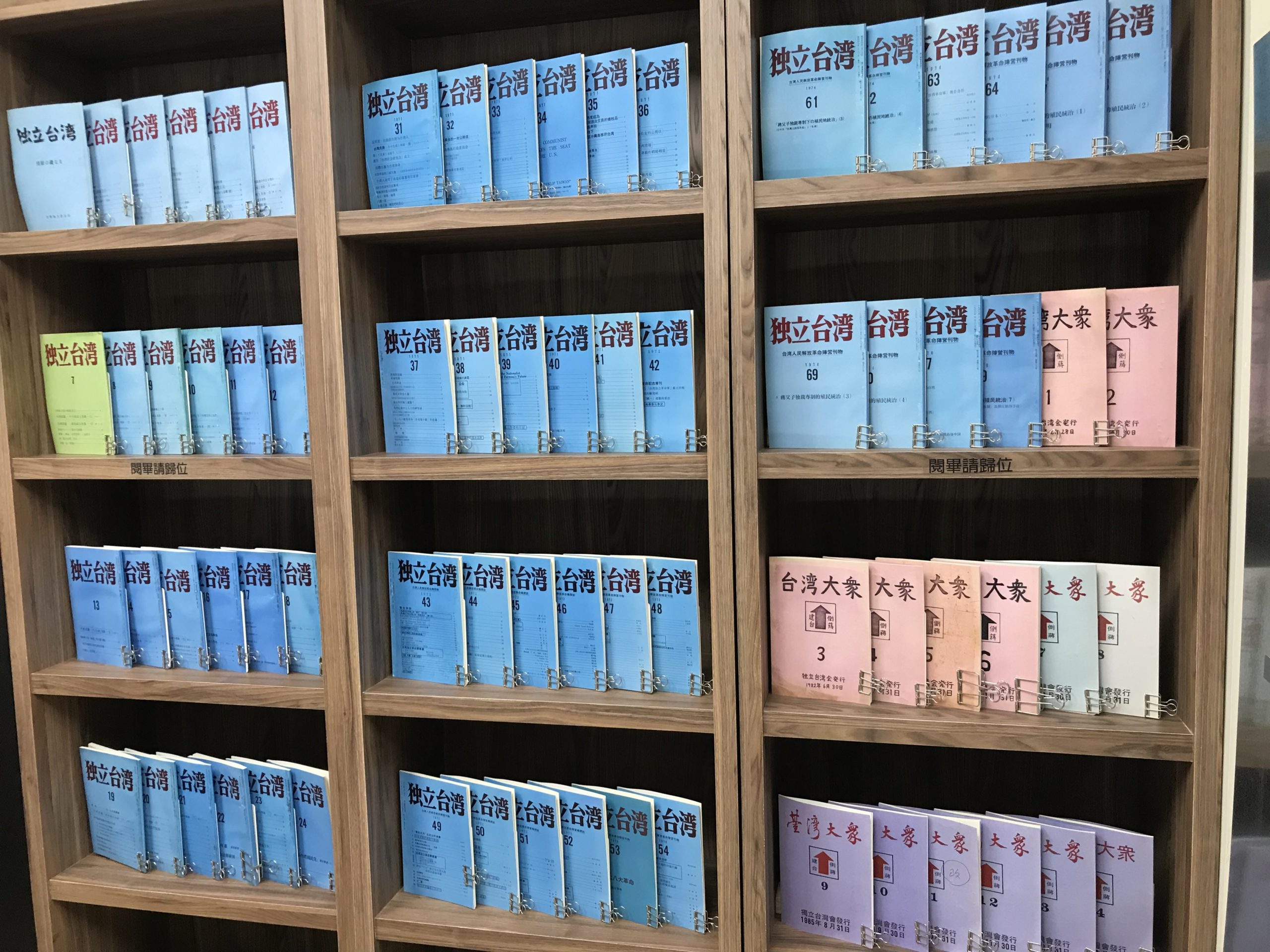

Publications by Su Beng during his lifetime. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

But after breaking with the CCP, Su returned to Taiwan, where he attempted to organize an assassination attempt on Chiang Kai-shek. When this failed, Su fled to Japan, where he started a noodle shop in Shinjuku, writing about the cause of Taiwanese independence from a left-wing perspective and training many independence activists. By the time that Su died in 2019 at age 100, Su was revered by many contemporary independence advocates—particularly those that saw themselves as advocating for independence on a left-wing basis.

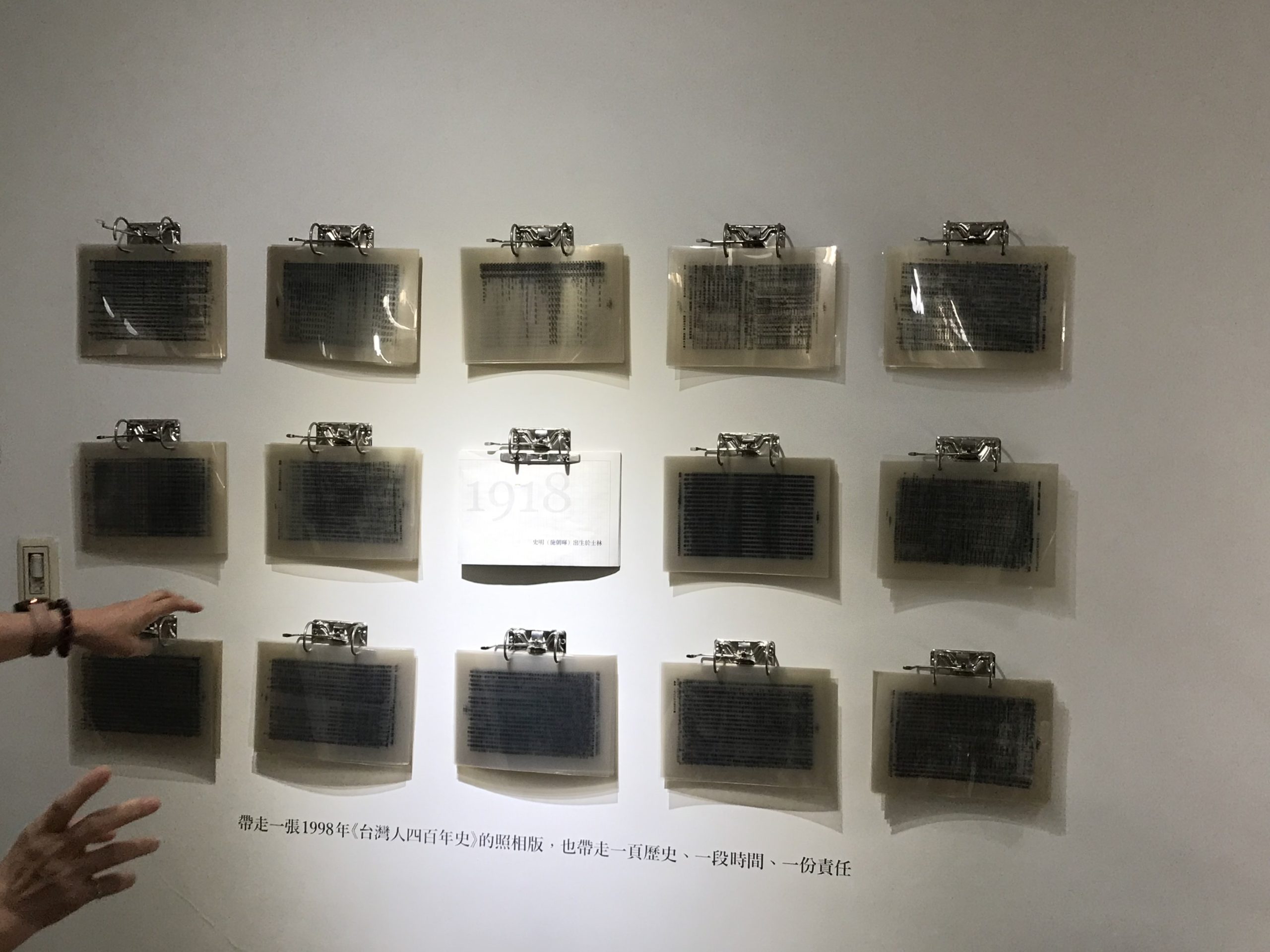

The museum displays a number of personal artifacts, including the bed that he slept on in his final years, his clothing, and the exercise bike that he used to keep fit even in his nineties. Otherwise, the museum displays some of the originals of Su’s writings, including the many issues of Independent Taiwan that he published, and copies of Taiwan’s Four Hundred Year History. Visitors are allowed to take home bootleg photocopies of Independent Taiwan that were distributed during the authoritarian period.

Photocopies of Su Beng’s works. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Otherwise, the museum features a recreation of the restaurant that Su ran while living in Japan, the New Gourmet in Ikebukuro, and a charming paper model depicting the premises as a whole. Videos shown on displays show Su meeting with younger activists, including those who are politically active today, while the museum also features audio recordings of the speaker trucks that he drove around Taiwan playing political messages using. A quick glance at the list of donors to the museums reveals a who’s who of contemporary Taiwanese activism, including individuals that have since won public office.

Some of the accompanying text touches upon relatively little discussed chapters in Su’s life, such as Su’s failed attempt to establish an underground radio station that could broadcast to Taiwan in Japan, or when Su ran an instant noodle factory in Japan. That being said, the significance of the museum is less in terms of its description of Su’s life, but the artifacts that it has within it.

Personal items of Su Beng’s before his death. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

The museum souvenirs are worth remarking on, including reproductions of political banners that Su used, a lego model of Su’s speaker truck, and kaoliang branded with Su’s image—including a flask in the shape of Taiwan’s Four Hundred Year History. The museum proves an accessible place to purchase some of Su’s seminal writings.

Given the COVID-19 situation, visiting the Su Beng Memorial Museum is limited to appointments, with two hours allowed per group of visitors. This proves ample time to look over the museum, which is presided over by Su’s caretaker in his twilight years, Huang Min-hung.