by Tyng-Ruey Chuang

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Tyng-Ruey Chuang

HSIEN-YU CHENG (鄭先喻), a Taiwan-based artist, has been producing intriguing works at a pace hard for the Taipei tech arts circle to keep pace with. He received the second Tung Chung Art Award in 2019 and held a special exhibition in the summer of 2020 at C-LAB (Taiwan Contemporary Culture Lab) for the award. Later in December 2020, he was part of a group participating in LAB KILL LAB, a week-long laboratorium directed by Shulea Cheang and organized by C-LAB, in the production of RICE ACADEMY Rice Bug Revolt. Right now he has a solo exhibition, titled injector after NULL, at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM) that runs from March 17 until July 4.

Cheng’s works offer a signature clarity once you get into them. His installations nevertheless can be confusing for new visitors. Some viewers feel lost when they fail to catch what is meant to get across. According to Cheng, some even got angry. It goes without saying that when in an art exhibition visitors take time examining and thinking about the works before their own eyes. However, people often want to “get it” in just a few glimpses; Cheng wants you to get it only after spending time with his works. It is not that they are puzzles for you to figure out. Rather, the passing of time is an essential ingredient—many of his installations only function after some duration of time at (or after) your presence. With the passing of time, there is also a question of uncertainty and luck. When you seem not to get it at all, you wonder why. Some anxiety may start to kick in.

Cheng’s discharged what you charged. Photo credit: Tyng-Ruey Chuang.

In the exhibition room at TFAM, a small metal box sits on top of an unassuming stand. It seemingly greets the visitors and asks them to charge their phones. Once your phone is being charged, the metal box seals itself. You are physically locked out of your phone. Why is that and what is next? How long will this take, and what will it do to your phone? You ask yourself. The phone is no longer under your control (or is it the other way around?). You are not getting answers. The time drags out as your phone battery being drained for no purpose. Is this the message Cheng wants to send you?

On three flat panels mounted on a wall in the room, big white blocks are slowly moving and rotating for no particular reason. The movement seems asynchronous nor related to the large woody blocks nearby, also in white. You try to give your best examination but find nothing. Only after you leave the scene do you hear some noises. Something is happening behind your back. Is that what Cheng wishes to make you think?

Cheng giving a guided tour. Photo credit: Tyng-Ruey Chuang.

You are not too sure but you are getting the ideas. On one April Saturday, Hsien-Yu Cheng accompanied me to his exhibition at TFAM. He greeted the staff in the room (as “aunties”, keeping the custom in Taiwan on referring to women about the age of one’s mother) and identified himself as the artist. He quickly fixed some glitches in the room. Some pieces had been unknowingly twisted by visitors, perhaps in an attempt to understand them. Before we knew it, the staff happily announced to the people in the room that they were in the presence of the artist and that he would give a guided tour. Cheng promptly took up the assignment.

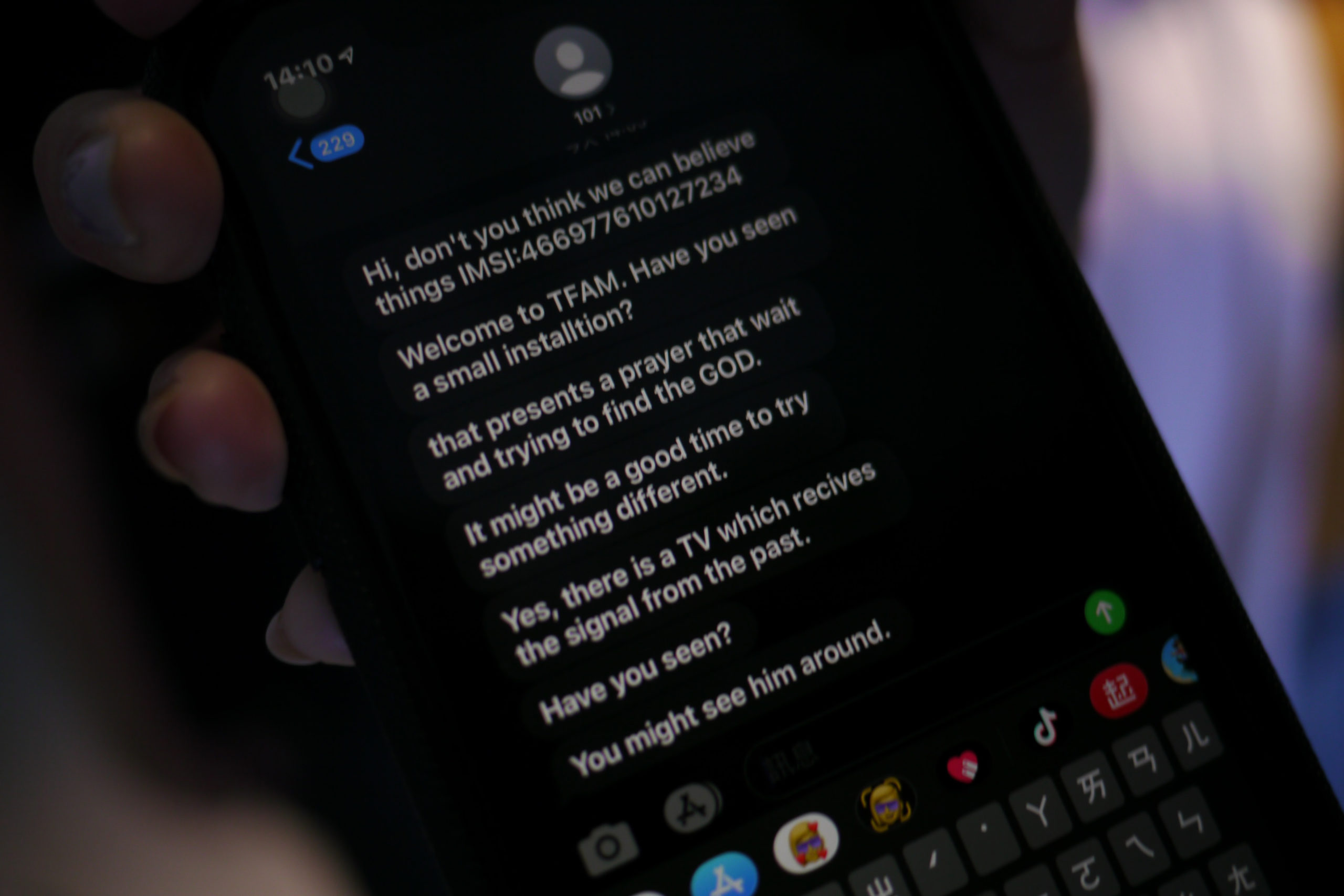

Several items at the exhibition are new iterations of his old works. He explained how Sandbox, a work from 2017, has undergone some changes so as to keep up with the practices of telecom operators nowadays. Cheng uses a small radio station in the room to jam the signals being transmitted between the visitors’ phones and the network stations. The jamming forces the phones to identify themselves and to talk over less secure channels. Cheng’s radio station exploits this weakness and is programmed to send out spurious messages to the confused phones. This takes effect only after the phones have been in the room for some time. While their phones are being fooled, museum visitors walk in a minimally decorated room and wonder why. The wandering visitors, if they are patient, will start getting texted when they are about to leave.

Cheng explaining Sandbox. Photo credit: Tyng-Ruey Chuang

Museum staff (“aunties”) experiencing Cheng’s Sandbox. Photo credit: Tyng-Ruey Chuang.

Phone being texted by Cheng’s Sandbox. Photo credit: Tyng-Ruey Chuang.

Cheng’s designs share the characteristics of making transitions in between different types of space. For Sandbox, it is from the physical space (phones in the room) to the information space (signals jammed and texts sent) and to the physical space again (phones leaving the room with messages left on them). Such playful transitions have been evident since his early works. For example, in Afterlife (not shown at TFAM), mosquitoes electrocuted by a lamp trap are transformed into shooters in a galaxy invader type video game where they defend themselves from the humans. That is, dead insects transit into digital ghosts in another space where they now seek revenge. This occurs only when the visitors stay long enough to witness innocent mosquitoes being trapped by the lamp (attracted to the room, perhaps, by the smell of their presence).

These transitions between spaces are meant to be experienced and articulated by people on site with the works. The ideas in Cheng’s works, however, can be equally appreciated in their abstract forms. In a sense, Hsien-Yu Cheng can be viewed as a concept artist exploring transitions (or the absence of them) and people’s reactions to them. What differentiates him from others is his excellent technical skills. Tech, as in tech arts, departs from its usual illustrative purposes for imaginative scenarios. Tech, for Hsien-Yu Cheng, is all in the realization of abstract concepts in matching implementations.

The title of Cheng’s current exhibition at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, injector after NULL, perhaps needs some explanation. A NULL pointer in computer memory points to nowhere. It often doubles as a delimiter separating the useful data from the undefined space. Playing with NULL pointers is error-prone, and we can imagine injecting something around NULL can be questionable.

Photo Guide for Picture IDs video on YouTube. FIlm credit: Very Mixer

At the time of this writing, unfortunately, the Museum is in lockdown (and probably will be for some time) as Taiwan is fighting against a sudden surge of COVID-19 cases. Going online, however, I can recommend a video interview from last November at the Taichung Opera, hosted by Escher Tsai, in which the artist talked extensively about his works (in Mandarin). You may also enjoy Photo Guide for Picture IDs (證件照拍攝指南), a thoughtful and amusing video on identity and surveillance, produced earlier this year by Very Mixer with Hsien-Yu Cheng, Sandee Chan, and Tsung-Fan Tan (in Mandarin with English subtitle).